A recent article in the Chronicle criticized how many newly-grads find themselves on a moral descent as they enter the workforce. Trinity sophomore Christian Sheerer writes that becoming “bad people that do bad things” is somewhat of an unspoken Duke destiny, clutching onto wealth as a measure of success.

The pomp, power, and prestige that surrounds recruitment season is unmistakable, and it’s no wonder why many Duke students pursue this route. Whether for financial security or stability—it’s safe.

I have no shortage of Chronicle articles stuffed in my back-pocket, ready to take down the perceived monolith of preprofessionalism. Don’t get me wrong, it’s a problem worthy of endless critique, but I’m beginning to realize there’s a little more nuance to the debate.

Discourse on preprofessionalism has devolved into a recycling of empty phrases about the “sell-out culture,” sandwiched between quips evoking images of mercenary, snake-like Duke students. Full disclosure: I’m guilty of this too.

Students are privy to the cultish obsession a portion of Duke undergraduates have with top consulting firms. One student, Trinity sophomore Alex Chao, posted a satirical meme on the Duke Memes for Gothicc Teens Facebook page reflecting on the “sell-out culture,” shown below.

Photo courtesy Alex Chao.

Cynicism and jest aside, Chao’s adaptation of the hierarchy, perhaps unintentionally, raises a salient point.

Twentieth century psychologist Abraham Maslow devised a “Hierarchy of Needs” to explain the motivating factors of human behavior, from basic physiological and safety needs to esteem and self-actualization. From the looks of it, Duke students are stuck somewhere on the ascent, not quite hoisting themselves onto the level of self-actualization, the fulfillment of one’s talents and life purpose.

Perhaps to gain a sense of belonging, following the herd of students to recruitment events provides affirmation; or maybe to feel accomplished and self-confident, students feverishly line-up summer internship opportunities from the get-go.

But how much of this instead stems from a false consensus that reflexively attributes Duke students to the “econ sell-out” trope?

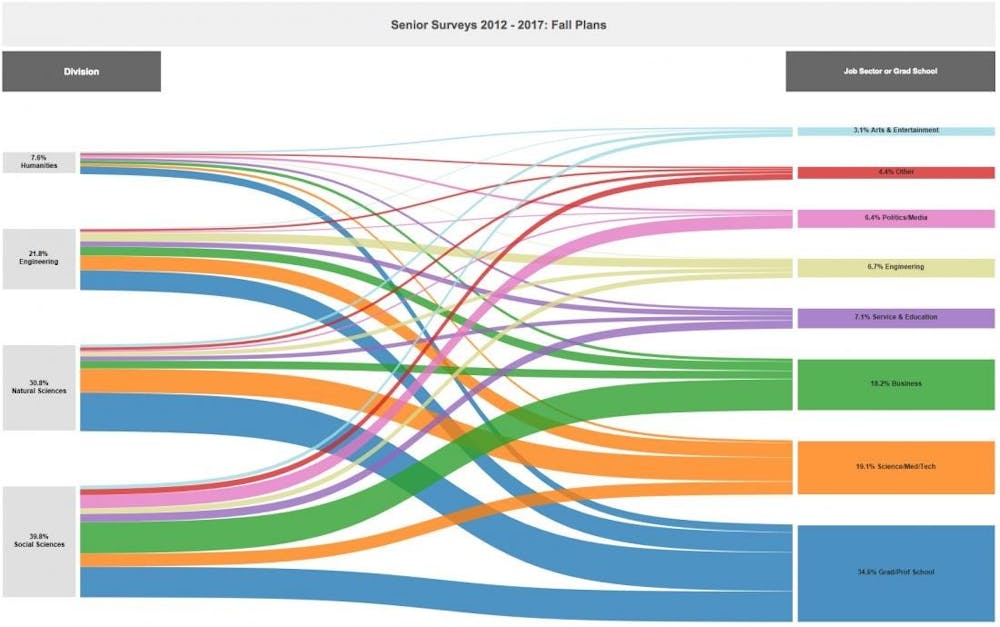

Photo courtesy Duke Career Center.

A survey of graduating seniors between 2012 and 2017 collected by the Duke Career Center, found that there is actually a fair amount of post-graduate plan diversity. The visualization above demonstrates disciplinary pathways to a wide range of careers and graduate/professional school programs.

The numbers don’t lie: students do more than land jobs at Facebook or Google. A large number of students report going to graduate school (34.6%) or scientific/tech fields (19.1%) over business (18.2%). Looking at the graph, it’s also important to note that there is a fair amount of representation, while not nearly as concentrated, in fields such as service & education, engineering, politics & media, among others.

So, why does this matter?

The idea of false-consensus, which is an attributional bias where people overestimate how widely accepted their own perspectives are relative to others, offers an explanation for why students hold sacrosanct this indistinct yet prevailing conception that just about everyone is a “sell-out.”

And in order to ascribe to this notion, you only need to meet a minimum threshold of exposure—through social media, conversations, and personal observations—to perceive it as true. Sometimes this threshold is met before students even arrive on campus for the first time, expedited through mechanisms such as the student Facebook meme page, for instance.

Yes, it is important to characterize, expose, and reprimand how the pre-professional culture dominates campus. But perhaps the reason it reigns king is because we reinforce it. We allow it to steer our motivations and commandeer our scope of possibility. Trivializing pre-professionalism through jokes or condemning the transformation of postgraduates into capitalistic devils certainly builds visibility, but doesn’t cut the virus from its power source.

To do that we need to change the paradigm.

A few weeks ago I attended a panel featuring Provost Sally Kornbluth, Vice Provost for Student Affairs Mary Pat McMahon and Vice Provost for Undergraduate Education Gary Bennett at Blackwell dorm on East Campus.

According to Vice Provost McMahon on East Campus several weeks ago, there are “exciting changes” afoot in Duke Career Center leadership and program structures that will help expand visibility to less known career paths. While specific details have yet to be revealed, McMahon believes that this will help combat the stigmatization many students feel when their post-graduate aspirations don’t align with the dominant pre-professional culture.

Because clearly students do more than sell their souls and care more than just to secure the bag—so why don’t we celebrate that?

Like any marginally provocative article, it’s my hope that people take this idea to heart. Sheerer raised some strong points. Even if there are only a handful of students who graduate securing lucrative, unethical positions of power, it is enough to question whether Duke actually teaches us how to be ethical. But it is equally as important to shed light towards those who pursue fulfilling careers that allow them to make a difference.

The biggest takeaway: don’t sell-out to the sell-out culture.

Catherine McMillan is a Trinity sophomore. Her column, “the devil’s archive,” runs on alternate Fridays.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.