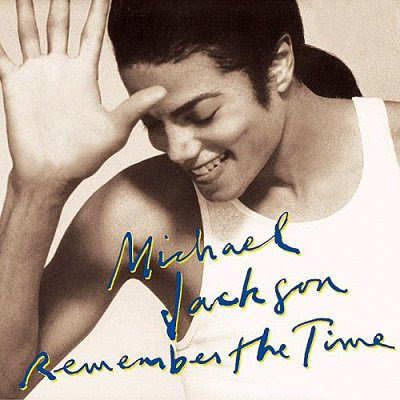

The final installment of the five-part series on Michael Jackson discusses the 1991 hit, “Remember the Time.” Aside from an incredible nine-minute long video, featuring cameos form both Eddie Murphy and Magic Johnson, the song is an excellent example of a widespread cognitive phenomenon. For the full Pop Psychology series Michael Jackson series, visit Part One on “Man In The Mirror,” Part Two on “Don’t Stop ‘Till You Get Enough,” Part Three on “Black Or White” and Part Four on “They Don’t Care About Us.”

With “Remember the Time,” I like to think that I have chosen to save the best for last. The second single off the Dangerous album remains my favorite Jackson song. There are a many features to like about “Remember the Time”: the smooth beat; the passion in Michael’s voice, especially near the end; the simple but contagious chorus. Ultimately, though, the defining characteristic in a Jackson track is in the reaction it evokes. More than any other Jackson song, “Remember the Time” makes me want to dance, dance, dance.

It's pretty clear that the song is devoted to Michael's reflections on a recently failed relationship.

“Do you remember when we fell in love?” he asks as the song opens.

“Do you remember the time when we first met?“ he inquires in the track’s chorus.

"I bet you remember,” he continuously reassures himself.

Michael seems positively certain that his romantic interest specifically remembers the exact conditions of the beginning of their relationship. He is also confident in his own memories of the situation. Now that their love has ended, Michael can only hold onto to his memories. “Those sweet memories will always be dear to me,” Michael sings. “And girl, no matter what was said, I will never forget what we had!”

Unfortunately for Michael, psychology says that he will most assuredly forget much of his time with this unnamed lover. After all, as cognitive psychologist Michael Gazzaniga writes, “accurate memories are an idea, not a reality of the human condition.” People continually overestimate the accuracy of their memories, but it is a sad fact of life that our recollections decompose much faster than we could ever realize.

Such rapid decomposition applies to all memories, no matter how insignificant or important. Even our most influential experiences prove susceptible to inevitable decay. Psychologists use the term “flashbulb memories” to define memories that people consider to be especially crucial or shocking. Kennedy's assassination, the moon landing and even Jackson’s own death fit the typical mold of flashbulb memories; events that burn themselves so strongly into the public consciousness that we all know (or think we know) exactly where we were when they occurred.

The defining study on flashbulb memories was conducted by Duke’s own David Rubin. On September 12, 2001, as the rest of the world grieved over the previous day's terrorist attacks, Rubin grieved as well, but he also saw a once in a lifetime opportunity as a memory researcher. Rubin had 54 Duke undergraduates give their recollection of one very important memory (where they were when they first heard about the events of September 11th) and one rather quotidian moment (a party, sporting event or study session). All participants were then brought back in either one, six or 32 weeks afterwards and asked to try and recollect both experiences.

Though people were able to give more details about their flashbulb memory, Rubin and his colleagues found that both memories decayed at about equal rates. So while people may feel that their “flashbulb memories” are impervious to inaccuracies, it appears that our mind treats these experiences as no different than even our most ordinary experiences. The only aspect that differentiates flashbulb memories from everyday memories is our own overconfidence in their accuracy. For Michael (and all foolhardy lovers) this means that despite what he may plead, the cherished memories of his partner will soon fade away. We all think that we "remember the time" of our lives' most significant moments, but as Rubin shows, this is rarely true.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.