Unnatural measures now mean additional consequences for students hoping to enhance their academic performance.

The Office of Student Conduct sent an email to the student body Friday regarding several changes to the Duke Community Standard as well as policies currently under review.

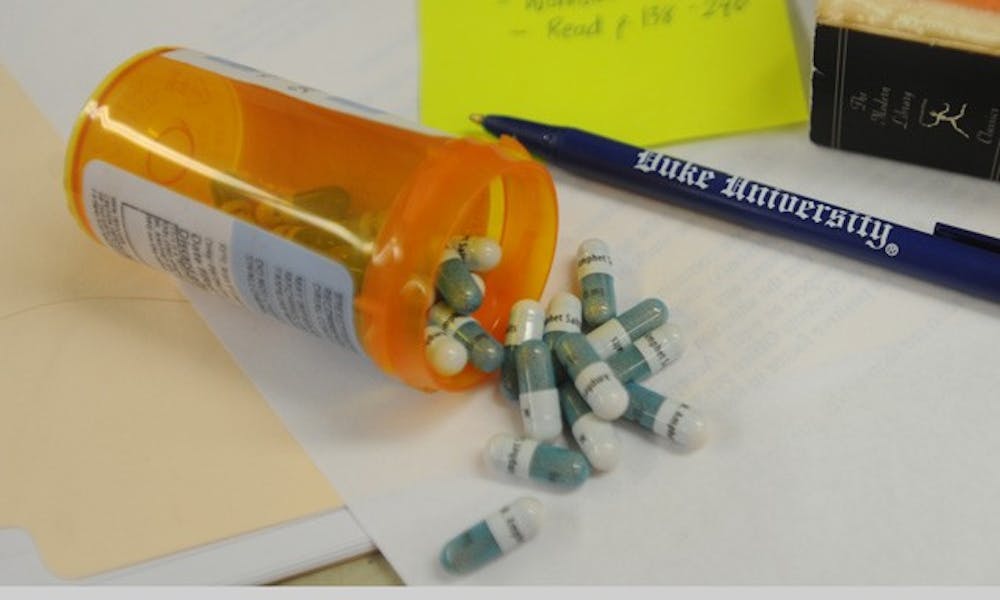

The unauthorized use of prescription medications—particularly drugs used in the treatment of Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder such as Ritalin or Adderall—in order to improve or enhance academic performance is now considered cheating as well as a violation of drug policy. In the past, the use of such drugs without a prescription was only a violation under the University’s drug policy.

Stephen Bryan, associate dean of students and director of the Office of Student Conduct, wrote in an email Monday that students were the driving force behind this particular policy change. He added that administrators and students admit this policy will be challenging to enforce because it is difficult to prove a violation.

“There is a perception—if not actuality—that Adderall abuse is rampant on campus,” Bryan said. “Enforcement is difficult, and the students who proposed this addition recognize this. They wanted to at least symbolically make a statement.”

The Office of Student Conduct Student Advisory Group—made up of Duke Student Government representatives, Greek Conduct Board members and the Honor Council—had been discussing the question of performance-enhancing drugs for almost three years, said junior Gurdane Bhutani, DSG executive vice president and member of the advisory group. The initial conversations were largely sparked by a Jan. 2009 Duke study, which found that approximately 9 percent of 3,407 students surveyed at Duke and the University of North Carolina at Greensboro said they had used ADHD medications without a prescription since starting college.

Bhutani noted that he believes identifying prescription drug abuse as an instance of academic dishonesty will deter students from using the substances illegally. If students the violate drug policy, he said, they currently only have to attend a substance abuse treatment program or sessions at Duke Counseling and Psychological Services. But if they violate an academic honesty policy, their academic reputation at the University could be in jeopardy.

“Students typically understand that the drug policy is fairly relaxed as it pertains to drug use,” Bhutani said. “Your status at the University won’t be affected except in harsh cases.”

Sophomore Taylor Elliott said he is aware that some of his peers abuse prescription medicine in hopes of improving academic performance, noting that usage is particularly high during reading periods and exams. He added that students who use ADHD drugs to improve their academic performance are usually those who slacked during the semester and are using the medicine while under the impression that it will help them catch up.

“It’s wrong because there are people who need those drugs, and they’re not supposed to be abused,” Elliott said. “It’s going to be extremely hard for that policy to be enforced because drugs trade hands all the time and administrators don’t know about it.... People can make a lot of money from selling Adderall, and that’s going to happen anyway.”

Abusing these drugs is more than just an honesty issue—it is a health issue, said Steve Nowicki, dean and vice provost for undergraduate education. These medicines are prescription-based for a reason—they are stronger than coffee or energy drinks.

“Any performance-enhancing drug can take you to an edge that can really turn out to be a disaster,” Nowicki said. “I regret that students sometimes feel as if they have to do extreme things just to be successful.... I’m not worried about the cheating part of it so much as I am about student health and well-being.”

Vice President for Student Affairs Larry Moneta said he is not convinced that policy changes—particularly those concerning drugs and alcohol—really stop students from engaging in those types of behaviors, but he hopes these shifts make at least a small dent.

“If this policy helps, I’m a fan—I don’t think it hurts or has any unintended negative consequences,” Moneta said. “If it deters one person, then it has served its purpose.”

Other changes to the University’s conduct policies include adding two student representative to the Undergraduate Conduct Board’s Appellate Board—which reviews appeals regarding student misconduct—and a decision to hold elected student leaders responsible for violations of University expectations by members of their groups in group activities, among other changes. The administration is also reconsidering the amnesty policy, which currently states that students who seek medical assistance for someone who is dangerously intoxicated will not endure disciplinary action.

Alcohol amnesty under review

The administration began to review current policy regarding the “Health and Safety Intervention” clause of Duke’s alcohol policy last academic year, Bryan said.

The Duke Community Standard currently dictates that disciplinary action for a violation of the alcohol policy will not be taken against students who seek medical assistance for themselves or others if no other University policies have been violated.

Changes, though, could make it so that if a student is in violation of alcohol policy while seeking medical assistance for themselves or others, it could influence the University’s disciplinary action if the student has a subsequent violation.

Bhutani said he and former DSG president Mike Lefevre, Trinity ’11—who also sat on the advisory board last year—have always opposed this proposal during advisory board meetings because they are worried it will remove the incentive for students to seek assistance for someone in medical danger.

The policy should be left untouched, Elliot said. He added that the current amnesty clause allows students to take care of their friends without worrying about themselves.

“Do [administrators] want to push back against [alcohol abuse] or make health the number one concern?” Elliot said. “Either way, people are still going to be stupid and not call because they want to cover themselves.”

In some instances under the current policy, students who make the call—who are also in violation of University alcohol policy—are required to make a presentation or write an essay, though the incident remains off of students’ records, Elliott added.

“It should be left the way it is because at least it won’t go on your record,” he said. “And people are willing to write a paper to save a friend.”

No changes to the amnesty policy will likely be implemented until Fall 2012, Bryan said, noting that conversations between students and administrators will continue throughout the rest of the year.

Appellate board additions

Two upperclassmen—one from the Trinity College of Arts and Sciences and one from the Pratt School of Engineering—will now sit on the Undergraduate Conduct Board’s Appellate Board, which reviews appeals from students and student groups who disagree with decisions made by the Undergraduate Conduct Board. Previously the Appellate Board had no student representatives.

Moneta said he and Nowicki decided together that it was time to include a student voice in these final appeal decisions.

“We’re impressed with [DSG] and the seriousness with which student leaders are handling matters—it’s a good time to expand student engagement,” Moneta said.

Bhutani said the representatives will be selected through a DSG application process. He expects DSG to release the applications later this Fall.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.