Ann Marie Fred was 10 years old when her father brought home a used Commodore 64 computer—a vestige of the 80s—from work. Fred, the girl who stayed after school to play Oregon Trail on the Apple computers, jumped at the chance to take advantage of her family’s new computer.

In addition to the Commodore 64, Fred’s father brought home a monthly computer programming magazine with simple programs that played songs or changed the colors of pixels on the screen. Fred said her first experience with programming was copying the programs from the magazine and modifying them to see what would happen. This was the first foray into tech for Fred, who now works for IBM.

“I never took a real programming or computer science class before I got to Duke, but I loved computers from the beginning,” said Fred, who graduated from Duke with a B.S. in computer science in 1999.

Fred’s story is not unfamiliar to many of the women in computer science The Chronicle spoke with. For them, exposure to computers and programming prior to college was key to staying in the field and could help explain computer science’s female recruitment problem.

Susan Rodger, director of undergraduate studies for computer science, wrote in an email that the department is aware of the low numbers of women in computing. However, they have made several changes over the past few years to mitigate the problem. Rodger, who is also professor of the practice of computer science, wrote that the department has tried to attract women to introductory courses such as CompSci 101.

“In 2010, we changed the programming language we use in that course from Java to Python, as we saw Python to be easier to learn for beginners,” she wrote. “It is more 'English-like' and more forgiving with errors. But more importantly we have tried to make CompSci 101 appealing to a broader group of students by focusing our problem solving with a wide range of problems.”

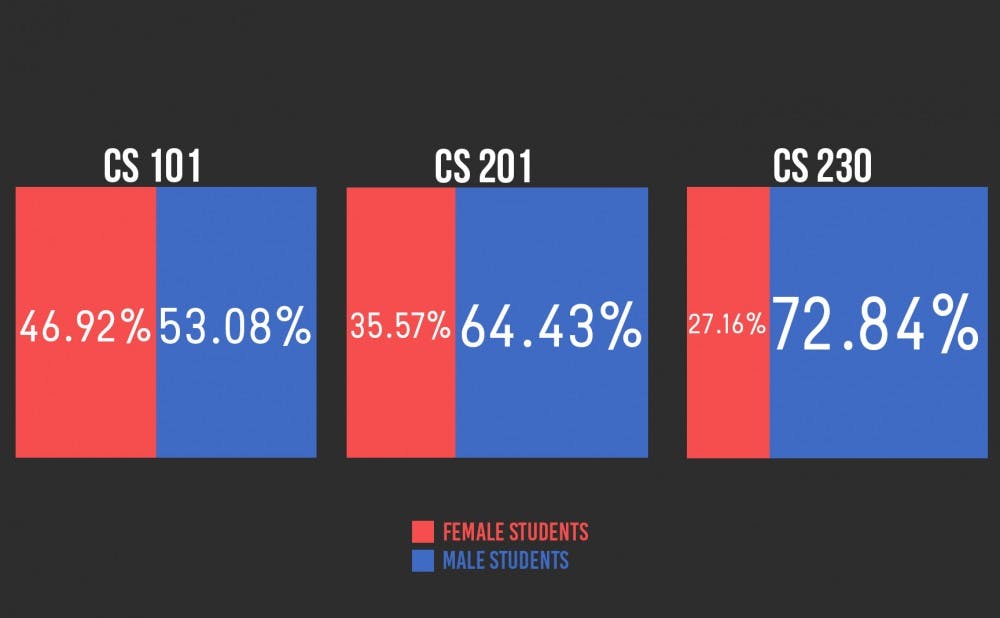

By one metric, the department has been successful. According to data obtained by The Chronicle, this semester’s CompSci 101 course is about 47 percent female. However, that success in female recruitment has not extended to female retainment—something Rodger wrote the department is currently working on. In CompSci 201, women make up about 36 percent of the class, yet that number drops to about 27 percent in CompSci 230.

“Our goal is to make the department more diverse at all levels—faculty, graduate students and undergraduate students,” wrote Pankaj Agrawal, chair of the computer science department and RJR Nabisco professor of computer science. “We have made progress in this direction but much more needs to be done.”

At the graduate level, female representation is even worse, but has improved over the past decade, according to data from the Duke Graduate School. The overall number of master’s students who have matriculated to Duke has increased 15-fold, but the number of female master’s students who have matriculated has only increased sixfold. For the Ph.D. program, there has been an even greater rise. In 2008, 10 percent of matriculated Ph.D. students were women. That percentage has risen to 25 percent for the 2017-2018 cohort.

Another interesting data point is the acceptance rate for women in graduate programs. From 2012 to 2016, the acceptance rate for female applicants was slightly higher in the master’s program. But, for the last two cycles, it has been lower. Since 2008, the number of female applicants to the master’s program has increased sixfold.

Ruth Willenborg, Trinity ‘85 and retired distinguished engineer at IBM, said that since graduating from Duke, female representation in tech has not changed much. In fact, it is a national issue. Although women represent nearly half of the workforce, only about 12 percent of engineers are female, according to computerscience.org.

‘The confidence thing’

Senior Shelley Vohr, who knew she wanted to be a software engineer before college, said her experience with programming prior to college motivated her to stay in the program.

Fred added that those who come into computer science without any understanding of it may find it harder to feel like they belong in the field.

“One of the things that people struggle with in early classes is they feel like a lot of their peers, especially their male peers, have had exposure to computer science before,” Vohr said. “So, they feel like they're less qualified, so they have a harder time pursuing it because they don't think they're going to succeed.”

Kate O'Hanlon, a third-year Ph.D. student in computer science, echoed some of the other women’s comments. In explaining why she stayed with computer science, O’Hanlon noted that she studied computer science at an all-girls college, which had more of a welcoming environment.

“The other main thing is the confidence thing. I don't like to say that women are less confident, but we are socialized to be less confident,” O’Hanlon said.

Vohr noted that it was easier to avoid a discouraging environment in her classes because she could choose the people she worked with. She has benefited from the size of Duke's undergrad computer science majors, with computer science being one of the most popular undergraduate majors at Duke.

The Ph.D. program, however, tells a different story. Although dozens of students graduate with an undergraduate degree in computer science, O’Hanlon’s Ph.D. class includes slightly more than a dozen people. In the 2008-09 cohort, 44 women applied to the Ph.D. program in computer science compared to 63 for the 2017-18 cohort, according to admissions data from the Graduate School. Of those 63 women, 12 were accepted, making it the highest percentage of accepted female applicants since 2010. Of this group of women, five matriculated.

Duke has also seen an increase in female role models in the computer science department over the past few decades. Rodger, who has been at Duke for more than 20 years, wrote that the number of female computer science professors has tripled during her time.

During Rodger’s first three years, the department only had three women faculty. Today, that number is up to a grand total of 10, three of whom are secondary appointments.

A male-dominated culture

O’Hanlon noted that the computer science department does a good job providing support for women, but not singling them out. She said that for the most part, she has not noticed being the one of very few women in her classes.

But, there was one class in which she did notice the gender divide, as she was the only female and computer science student amongst male electrical and computer engineering students. The class had an odd number of people and the professor kept splitting the group into pairs.

“I did end up withdrawing from the class because as the only female and the only CS person and keeping being forced to break into these pre-existing groups was just too hard,” O’Hanlon said.

O’Hanlon has also noticed differences in how men and women communicate. She said that there have been times when she was frustrated by the directness and competitiveness of her male peers. But, she attributed some of the frustration to her familiarity with an all-girls environment in undergrad.

“That has been a little bit of struggle for me—just working in groups where I am the only woman there and the men are all communicating in a very direct, almost rude way compared to what I'm used to,” she said.

As a graduate teaching assistant, she noted how sometimes female undergraduates were more “polite” when asking for help than men, who were vocal in situations like office hours.

In the industry, Fred, who said she was not speaking on behalf of IBM, noted that insensitive statements have been directed at her. For example, people have suggested that because she is a woman, she is infallible and would not be fired. She said she has gotten good at calling out those who have made such remarks.

Though many of the women The Chronicle spoke with described hearing insensitive remarks and unpleasant cultures, none of them reported instances of harassment in their experience, but they do believe harassment is an issue for the industry.

Engaging men

Over the summer, multiple women in Silicon Valley spoke out against a "culture of harassment." One notable instance involved former men’s basketball player Justin Caldbeck, Trinity '99 and a venture capitalist. In June, The Information reported that half a dozen women said they faced unwanted advances from Caldbeck, who has since been ousted from his company. Caldbeck recently visited Duke to talk about “bro culture.”

“I think this underscores how important it is to teach all of your managers and [human resources] how to stop harassment and retaliation,” Fred, who has not had issues with HR at her company, said.

Vohr, who works for GitHub, said that she believed the culture of a company is very much influenced from the top.

“If you have leadership at a company that's really focused on not letting that culture get out of hand, then I think that trickles down,” she said. “You notice it a lot at smaller companies that may be lacking HR, may be lacking other important functions.”

Despite these potential roadblocks, many women are still motivated to be successful in the industry. Vohr said that one mindset some people take is to ignore equity issues and focus on themselves, but that does not work for her.

“Personally, [comments] do tend to roll off me, but that doesn't mean they roll off of other people,” Vohr said. "It's easy to be like 'This doesn't affect me,' so I can stick my head in the sand and not worry about it. But, that doesn't really help anyone.”

Willenborg also suggested that more of an effort needs to be made to involve women in the nontechnical aspects of the industry. This would include designing the interface or interacting with clients.

All the women interviewed agreed that involving men in conversations about female representation was part of the solution. Fred noted that doing so starts with building trust with male peers.

“The best conversations I've had around this have been with men I've been working with for a while, usually in a pretty informal setting, like over lunch or at a party at somebody's house,” she said. “Then, they're more willing to open up about it.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Class of 2019

Editor-in-chief 2017-18,

Local and national news department head 2016-17

Born in Hyderabad, India, Likhitha Butchireddygari moved to Baltimore at a young age. She is pursuing a Program II major entitled "Digital Democracy and Data" about the future of the American democracy.