Given the popularity of the computer science major, it's likely that you've heard some of your friends complain about a coding assignment.

But what percentage of those friends are female?

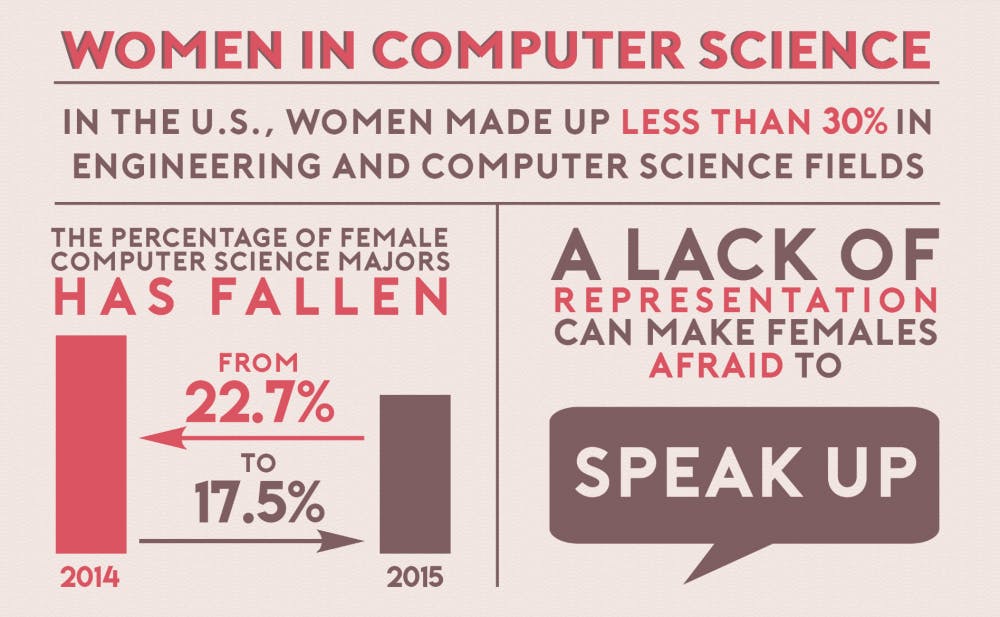

Competition for tech talent is intense, with new computer science graduates commanding one of the highest starting salaries. However, men still hold a disproportionate number of jobs in computer science fields. A National Science Foundation study in 2013 found that women's participation in engineering and computer science fields was less than 30 percent. Some students and faculty at Duke have noticed the gender gap in the computer science major.

“Nationwide, there are few women in computer science at all levels of the pipeline, from undergraduates to graduate students to faculty, decreasing as you get higher in the pipeline,” said Susan Rodger, director of undergraduate studies in the computer science department.

Nonetheless, the department has experienced a explosion in student demand among both men and women for entry-level computing courses, Rodger said.

“We are quite proud that we have managed to get 50 percent women in CS 101, and the percentage of women going through the major is steadily increasing," she said.

However, according to data provided by Frank Blalark, assistant vice provost and university registrar, the percentage of female computer science majors actually fell from 22.7 percent in 2014 to 17.5 percent in 2015.

Rodger noted that she has also observed an emerging trend for female computer science students to exit the major as course levels get higher.

Junior Larissa Cox, a computer science major, said that these trends are fairly accurate based on her experiences.

“Lower level and introductory courses tend to have a more equal number of males and females, but as you move further into the major, [computer science] classes at Duke are definitely dominated by men, particularly in the upper-level courses,” Cox said.

Other computer science majors disagreed, however, including senior Rachael Lee and junior Jennifer Du. Lee noted that her higher level classes “generally have the same breakdown as [her introductory] class," while Du said she felt that “there is an almost even proportion of men and women in [her] computer science classes.”

Some students said they feel the impact of gender disparity on classroom dynamics. Cox explained that the perceived lack of female representation in upper level computer science classes sometimes makes females more fearful to speak up.

“In classes that are taught by men and dominated by male students, it can be extremely difficult to participate, and it's even more difficult to give input and make yourself heard in group projects that are dominated by male peers,” she said.

Rodger noted that she believes one of the main reasons for the gender gap is that many women lack exposure to computer science in middle school or high school and therefore are either unaware of or have misconceptions about what computer science entails.

“Women may have the misconception that they will sit in an office all day by themselves writing code,” she said. “Computer science careers are not like that. Computer science involves collaboration with people in other disciplines to solve challenging problems, and programming is only a small part of computer science.”

To help combat some of these stereotypes, Rodger has run summer workshops for the past nine years, teaching middle school and high school teachers how to program and integrate their new knowledge into the classroom.

The department has also been actively implementing initiatives to improve gender diversity in computer science and to develop strategies that make computer science more appealing to women. For instance, it currently partners with the National Center for Women and Information Technology to support engagement in computing at both the student and professional level.

Since 2007, the department has also taken students annually to the Grace Hopper Celebration of Women in Computing Conference, the world’s largest gathering of women technologists. Just two weeks ago, 37 students, including Du, were able to participate in the conference's networking and learning opportunities.

Looking to the future, Rodger said the department hopes to take a more analytical approach to tackling the gender gap in computer science.

“We are doing several things such as collecting data about the number of women in our CS courses, surveying our students and having focus groups with female students, so we can get feedback from them on their experiences," Rodger said. "We would like to use the data to determine what we can do to increase the number of women in the major."

Currently, Rodger said, the focus on gender diversity starts at the entry-level courses.

“Several years ago, our department tried to make CS 101 more appealing to a wide variety of people," she said. "We talk about role models of different genders and ethnicity, many of them alumni. We created more examples to include more disciplines and large data files. For example, we find genes in long DNA strands. We compute the largest earthquake from earthquake data over the past 30 days from all over the world."

First-year Robyn Kwok, who is currently taking the entry-level CS 101 course, intends to continue with CS 201 next semester and eventually pursue a computer science major.

“I enjoy the way computer science is taught at Duke," Kwok said. "The problem sets in particular are very well set and help me to understand new concepts by implementing them to solve relevant problems."

Rodger has high hopes for increasing female participation in computer science, noting efforts by the department to decrease the gender gap have paid off.

"For 20 years, we had only three women faculty," she said. "Now, we have six women faculty and eight if we count [joint appointments] in other departments."

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.