Recent incidents of racism at universities across the nation have brought the verdicts of student disciplinary action into the spotlight, with some questioning due process and the role of freedom of speech on campuses.

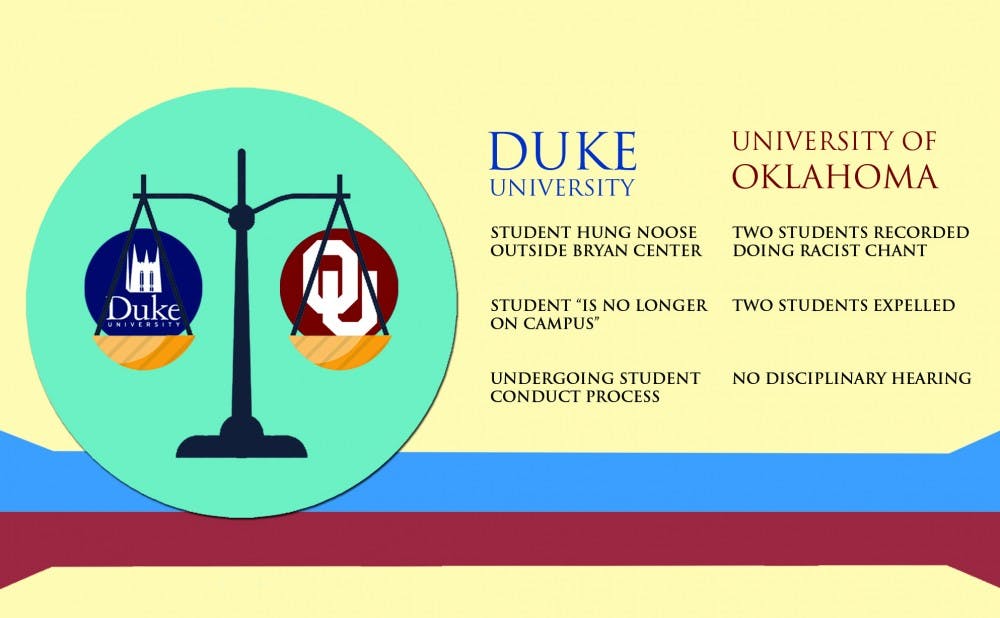

The morning of April 1, a noose was discovered hanging on a tree outside of the Bryan Center. This incident closely followed campus backlash after a black female student reported being the subject of a racist chant on campus. The same chant resulted in the expulsion of two University of Oklahoma students March 10. The students—members of Sigma Alpha Epsilon fraternity—were caught on video singing the derogatory song days prior to President David Boren announcing their expulsion. Duke administration said that the student who hung the noose came forward and is no longer on campus, but declined to reveal the perpetrator's name.

Both incidents quickly became national news—sparking outrage not only on the two campuses, but across the country. In addition to sparking discussions about race relations on campuses, the quick disciplinary action taken has caused some to question the roles due process and free speech have within universities.

The two faces of due process

There is an important distinction between public and private universities regarding due process on campus. Public universities like OU are constitutionally bound to provide due process for their students, said William Van Alstyne, a Duke law professor from 1965 to 2004. He added that private schools like Duke are not bound by such constraints.

For public schools, Van Alstyne explained, minimum due process means providing notice of the charges and the opportunity to be heard in a disciplinary hearing. He noted, however, that just because private institutions are not constitutionally bound to due process does not mean it is not provided.

Vice President for Student Affairs Larry Moneta said Duke takes pride in maintaining fairness in its campus judicial system.

“I don’t believe that we provide fewer rights to students engaging in the disciplinary system,” Moneta said. “Annually, a fairly large group of people, students, faculty and staff, come together to review and revise our policies based on legal testimony, student testimony and as the community sees appropriate.”

Less than 48 hours after the noose had been hung, the University announced that the student who hung the noose came forward and was no longer on campus. At that point, however, administrators declined to specify the circumstances in which the student left Duke or provide any details about the student's identity. The student is going through the University's disciplinary process, and Duke is cooperating with state and federal officials investigating the possibility of criminal charges, administrators said at last Thursday's press conference.

The lack of transparency about what exactly happened to the student involved in the noose incident makes it hard to know whether the student was fairly treated by the university’s disciplinary process, said Robert Shibley, Trinity '00, Law '03 and executive director of the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education.

In a letter Shibley sent to President Richard Brodhead Monday, he said in particular that the phrase “the student is no longer on campus” is difficult to interpret and makes it difficult to gauge whether due process was achieved.

“Did the student voluntarily leave campus, or was he or she forced to leave by Duke?” the letter reads. “If the latter, what procedures did Duke follow? Did the student present an immediate danger to campus if he or she were to remain?”

Because the circumstances surrounding the expulsions at OU were more transparent, Shibley said he feels sure that constitutional due process rights were not provided for the OU students. The two students were expelled without a disciplinary hearing March 10 shortly after a video of the racist fraternity chant went viral.

“If there is an actual threat to safety, the university is legally allowed to remove the person immediately,” he said. “In the OU case, however, nobody indicated the students had threatened the physical safety of anyone on campus. Instead, President Boren expelled them and did it without any sort of hearing, so I think it's pretty clear President Boren overstepped his bounds.”

Free speech restrictions?

In addition to drawing questions of free speech, the expulsions at OU have raised concerns regarding students' free speech rights on campus. Stuart Benjamin, Douglas B. Maggs professor of law, said there are significant First Amendment concerns involved with the OU case, noting that the OU expulsions clearly violate the students' free speech rights.

“Under current case law, you can’t punish them for their song, however heinous or unpopular,” Benjamin said. “If they wanted to bring a case, I have little doubt they would win the case.”

As with due process, private universities like Duke are held to a different standard and not constitutionally required to employ First Amendment standards in dealing with speech on campus, said Michael Newcity, adjunct associate professor of Slavic and Eurasian studies.

If Duke were a public university, however, he noted that hanging a noose on a tree might be similarly protected by the First Amendment, provided that the noose was not designed to target any specific individual.

“States and the federal government can make it a crime to threaten or intimidate someone, so if you hung a noose on someone’s office door, that is arguably an act which does threaten or intimidate,” Newcity said. “If this noose was not directed at any one individual I don’t see how it could be deemed unprotected.”

Shibley once again argued that Duke’s lack of transparency surrounding the incident makes it difficult to determine how speech was treated. He noted that the school will not release what the suspected motive behind the act was.

Moneta added that Duke has always made it its goal to protect free speech on campus despite the absence of constitutional mandates to do so.

“Duke’s approach essentially mirrors First Amendment requirements,” Moneta said. “We do not have speech codes, we do not prohibit and in fact we promote free expression. Our processes here are based on behavior, not verbal or symbolic expression.”

At Thursday's press conference, Moneta said that it was "way too soon to determine" exactly which provisions of the student code of conduct were violated and what the sanctions might be.

The incidents at OU and Duke raise "an important philosophical question" for universities, Newcity said.

“If you accept the notion that a university should be a bastion where students and faculty can say virtually anything, at least within the broad boundaries established by the First Amendment, it raises a serious question about disciplining a student for saying something that is clearly protected speech,” he said.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.