How to write about Toni Morrison? I’m not sure how much or even what exactly the name conjures for you. Like most things in my life, it’s referential and, in being so, largely nostalgic:

Tacked to the whiteboard of a high-school classroom, a blown-up photo of my Morrison-obsessed Favorite English Teacher Ever huddling next to the authoress herself, so distinctly posed that students asked her if Morrison was a wax figure. Durham’s own N.C. Mutual Life building, referenced in the first line of Song of Solomon. Oprah and Obama’s fangirl/boy status. Morrison’s silvery cornrows and bountiful, conversing hands that could only sit next to “magisterial” in the dictionary. Those names—those wide-ranging, often biblical, outrageously creative names: Pilate, Pecola Breedlove, Milkman Dead, Soaphead Church, Guitar. The Google doc in which I signed up for this review, where each of the Recess editors inserted some variation on our decidedly “we’re 20-somethings!” title for her: “TONI F*****G MORRISON.”

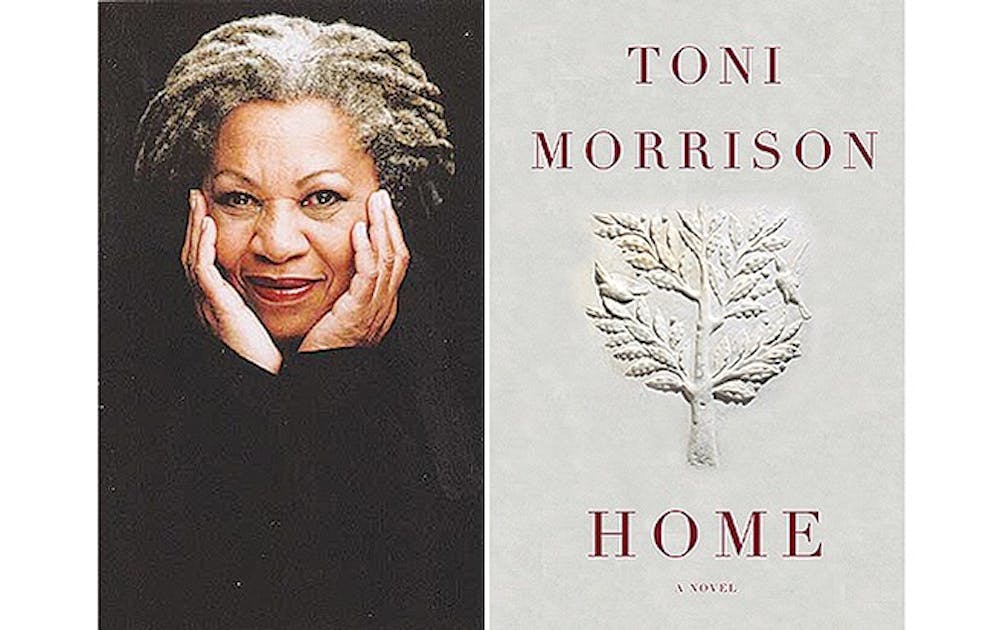

It was with a blush that I read the slightly more mature but still over-adulatory book jacket assessment of Morrison in light of her new novel, Home. “America’s most celebrated novelist.” A 145-page sliver of an offering, Home is easy enough to describe plot-wise. Frank Money, one of many narrators, is a Korean War vet making his way back home to Lotus, Georgia—the most recent of Morrison’s small-Southern-town-where-nothing’s-really-happening fictional locales. Despite the novel’s relative brevity, it parallels an Odyssean homecoming narrative, replete with central female figures that circulate around Frank, helping him navigate his journey as both incentives and remembrances of things past. His objective to reach his sister Cee is expedited by the foreboding words of a brief letter: “Come fast. She be dead if you tarry.”

Making his post-war pilgrimage through Chicago and ultimately down South, Frank meets a spread of (mostly helpful) characters plucked from Morrison’s imaginative repertoire, which often straddles the epic and the quirky with choreographic ease. And, more than anything else in this novel—and especially the reductive synopsis description of “an apparently defeated man finding his manhood”—it is these characters, and their experiences as expressed by Frank, Cee, their grandmother and an omniscient narrator, that reaffirm Morrison’s artistic weight. At one moment there’s Frank, boarding a Greyhound bus bound for somewhere, “dutifully [sitting] in the last seat, trying to shrink his six-foot-three-inch body” while clutching the sandwich bag prepared by the novel’s first Samaritans, Jean and John Locke (those names!). Immediately after, Frank’s hyper-observance (as filtered, notably, through the third-person narrator) picks up on the snow-covered environment whizzing by and visually transforms it according to his own perceptions: “So, as was often the case when he was alone and sober, whatever the surroundings, he saw a boy pushing his entrails back in, holding them in his palms like a fortune-teller’s globe shattering with bad news; or he heard a boy with only the bottom half of his face intact, the lips calling mama.” The war’s effect on Frank is obviously traumatic, but, for most of the novel, only in a vague, nostalgic sense. This unresolved quality pervades Cee’s narrative as well as Frank’s relationship with the enterprising costume designer Lily, one “slid into” and then “stutter[ed]” out of. The novel is more a progression of unfoldings than tightenings and clarifications, and Morrison’s lyricism matches these qualities perfectly.

Home is, in this way, supremely associative—much in the same way at least our generation upholds Morrison according to various standards and experiences that can somehow congeal around declarations like “she’s so good” and “a prose goddess.” The whole time I read Home I couldn’t subdue the little voice churning in the back of my head, reminding me of sublime experiences beginning her oeuvre with The Bluest Eye and ending it, until now, with Paradise in 12th grade. Similarly, I discerned echoes of her previous novels throughout Home: Pecola Breedlove’s child-eyed perceptions of sexuality in Cee’s eventually disclosed medical abuse, the self-sustained women of Paradise in Lotus’ female spiritual healers, the racism that subsumes Home, and the rest of Morrison’s novels, much in the same way it refuses to escape our cultural consciousness. Home is a space in which reference and retrospect mix with the present-tense. When we, as readers, reach the end, we—like Morrison’s characters—want some form of finality, but not one that embodies cliché and stability in the sense of a traditional “home.” Morrison, whose oeuvre works to deconstruct that privileged sense of place, seems to know that. Home the novel and ‘home’ the idea aren’t so much physical places as they are signifiers of the drive to move forward without losing your backstory, head strapped on firmly, with those you love at your side.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.