Perhaps the most important thing I learned during my PhD was how to fail. Prior to the doctoral stage, academics is largely based on defined problems with known solutions. All of our previous training supports the sense that failure is unacceptable and should be avoided at all costs. But failure is an intrinsic and critical component of scientific research. Thus, to succeed in research, one must learn to fail with grace.

And let me tell you, I failed a lot.

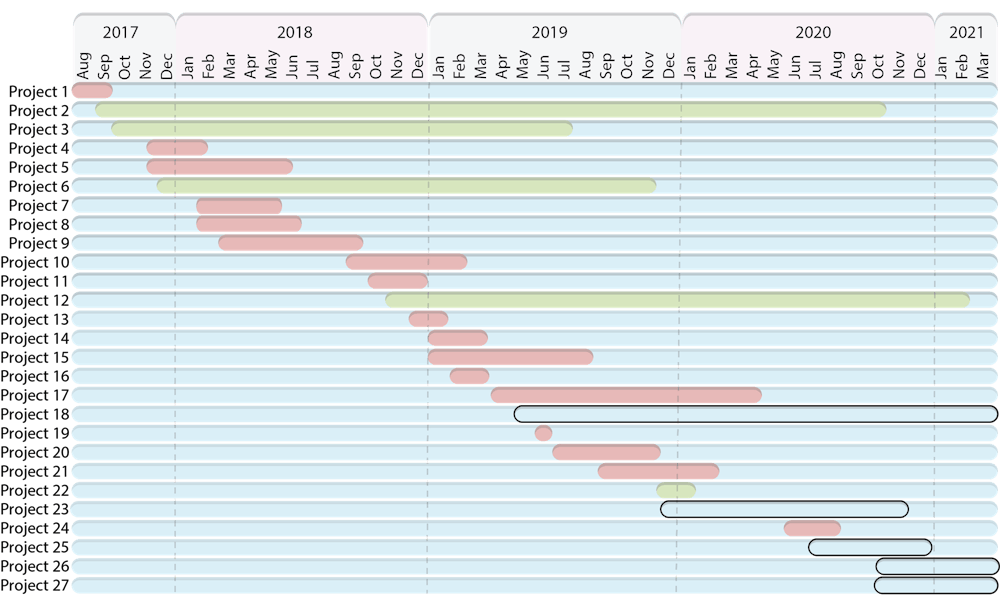

While preparing my PhD defense, I looked through my lab notebooks to remind myself of what I had worked on over my four years as a PhD student in Electrical and Computer Engineering at Duke University. I was honestly surprised by what I found. Of the 27 projects I led over my tenure at Duke, 17 had failed. I have certainly had success, with five publications, but the vast majority of my research ideas didn’t succeed. While I don’t have statistics on research success for the broader community, I can say with confidence that a researcher who has not failed after four years of work is either working on a problem that is too easy or is lying to you.

I know this because research is, almost definitionally, difficult. If the problems we are working on were easy, they would have already been solved. Hard problems are often the most exciting to work on. But getting to a solution can be frustrating, and the path will almost certainly contain multitudes of dead ends. So, remember, if you are just starting your research career, or are demoralized after months or years of limited progress, what differentiates a good scientist from a bad is the ability to lean into the failures.

Over my nearly 10 years in research—first as a research & development engineer in industry and more recently as a PhD student—I have developed several methods to cope with the inevitable setbacks associated with hypothesis-driven work.

First and foremost is to learn when to give up. There is, unfortunately, not a steadfast rule one can follow to know when to move on from a project. It is going to be different for each research direction and each individual project and individual contributor. Personally, I have a ranked system on excitement about projects and as a project languishes in the doldrums of limited progress, it will gradually move down the list of excitement. Once a project has fallen past a threshold, I generally let the idea go. This works for me but may give many others anxiety. The fact is, it takes time to develop the intuition to know when to call something a failure.

Researchers at the start of their careers constantly blame themselves for the lack of progress, leading to endlessly repeating the same procedure and praying for different results. While individual error does occur, often this strategy only leads to more frustration with weeks or months of delay. Strong mentorship can play a pivotal role. Working with a mentor as an early-stage researcher can exponentially propel intuition-based decision making. Further, a mentor in the same field can assist with developing the tools to discern whether a failed experiment is caused by individual error (leading to a repeat of the same experiment) or by an incorrect hypothesis (leading to a shift of experimental plan). Finally, a mentor should help guide a novice towards a conclusion of a project, whether that be publication or acceptance of defeat (which should still be publishable—but that is an entirely different conversation). But don’t take this as a recommendation to blindly follow a mentor’s advice. If the advice of others doesn’t feel right, continue down the path of investigation. At the end of the day, you are the one who must make the decision to let an idea go.

This leads to the next step in accepting failure: find a way to move on. It is immensely easy to become mired in self-doubt and malaise about an incorrect hypothesis leading to weeks or months of now-useless data. I have gone through it more than once, including once with an experiment indicating that three years of data was due to sensor drift, not actual detection of a known quantity. I have found a way to get over my failures that works for me. Personally, I always work on as many ideas as I can; no single idea is overly precious in my mind. For me, simultaneously working on a little over five projects, on average, allows me to focus on other potential successes rather than concentrate on the failures.

Running multiple projects at once is, obviously, not possible for many types of research or research personas. However, I believe there is one specific action that could help all scientists move forward: Keep a list of questions that you are interested in. This should be a living document based on your own research, conversations with collaborators, and reading papers in your field and in fields that may seem tangentially related but that you think may offer important synergies with your field. Throughout my PhD, I have spoken with friends and colleagues about moving on from failure, and those who are the most successful all have a list. What is on the list? This often emerges naturally during the investigation process and ranges from mundane questions on definitions to pointed questions about methodology to broad ideas for future investigation directions. Beyond dealing with failure, I have found this also helps with further investigations after a successful publication. For better or worse, science is a constant grind where ideation is a prized commodity.

Even with multiple layers of backup and avenues for fruitful investigation, research can be an exhausting and emotionally draining process. Failure is hard to deal with. The limited discussion about failure we see is exclusively provided by highly successful people reminiscing about their failures, whereas all others sweep their failures under a rug—to the detriment of the entire community. Almost every month, an article is published discussing the need to change this dynamic. Almost every month, someone states the need to publish negative results. And still there is no meaningful change.

So perhaps a different approach is necessary. To whoever is reading this, just remember that failure is not embarrassing. Everyone fails. Acknowledge the failure and find a way to move forward, whether that be from pivoting to another avenue as determined by your personal list of questions, or by bouncing ideas back and forth with collaborators and peers, or via some other method. Failure is a natural part of research. Perhaps remembering this will help you succeed. I know it has for me.

Nicholas Williams recently earned a PhD in Electrical and Computer Engineering from the Graduate School.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.