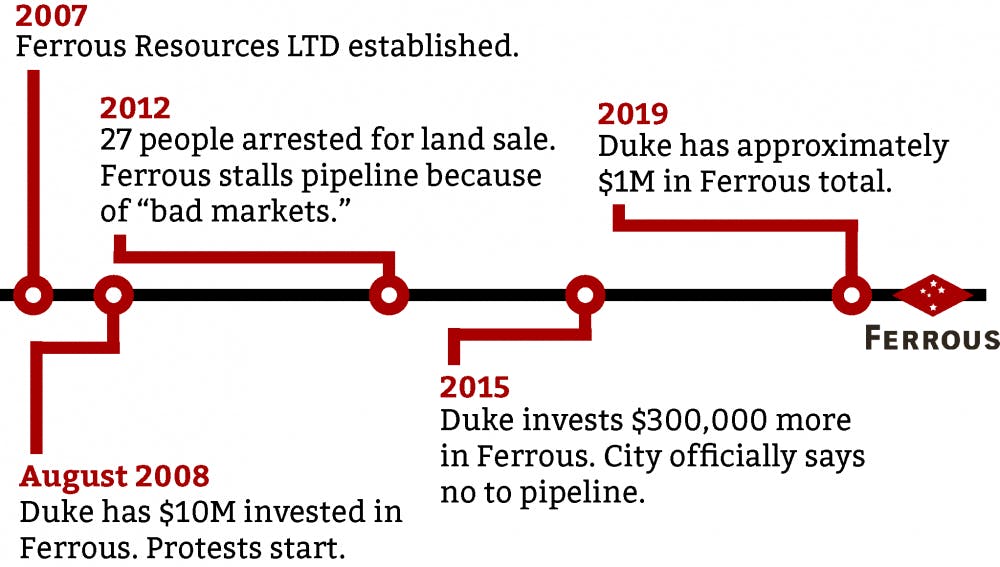

When the Paradise Papers made headlines in 2017, the confidential documents revealed Duke’s investments in Ferrous Resources—a company whose plans to build a controversial pipeline sparked years of protests in Brazil.

A new investigation by The Chronicle found the specific amount of those holdings: between 2008 and 2015, Duke invested a total of $10.3 million in Ferrous.

The University invested in Ferrous amid the company’s entanglement in alleged government corruption. In 2012, the Brazilian federal police arrested 28 people—mostly government officials—for allegedly diverting more than $13 million from the city of Presidente Kennedy through public bidding fraud.

The police report alleges that Ferrous was granted tax incentives in exchange for buying land at artificially high values from companies owned by government officials. Ferrous submitted a brief to the court stating that it was granted those incentives for bringing business to the region. Further information about the trials—which are still ongoing—is under an order of secrecy by the case’s judge.

As of December, the University’s holdings in Ferrous stand at approximately $1 million, wrote Michael Schoenfeld, vice president for public affairs and government relations. He declined to comment on whether Duke had sold shares since 2015.

Both Schoenfeld and Neil Triplett, president and CEO of Duke Management Company (DUMAC) and Gothic Corporation—Duke’s two investment groups—declined to comment on whether they were aware of the protests or Ferrous’ entanglement in the alleged money laundering scheme.

Lawrence Baxter, the chair of Duke’s Advisory Committee on Investment Responsibility, said the committee is “not in a position to offer comment” on Duke’s investments in Ferrous because it is not authorized to speak on behalf of the University’s investors.

And although there is an established process for community members to inquire about investments—as well as publicly available tax returns that must summarize Duke’s holdings—many details about the University’s investments are still unclear.

The Paradise Papers consist of 13.4 million confidential documents about offshore investments, which were leaked to journalists Frederik Obermaier and Bastian Obermayer at the German Süddeutsche Zeitung. The newspaper shared the documents with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, which then organized a global reporting collaboration. The Chronicle investigated the Paradise Papers as part of ICIJ’s Alma Mater project, which explores offshore investments made by universities.

This investigation digs into the at least 10-year relationship between Duke and Ferrous, shedding a rare light on how the University manages its investments behind closed doors.

You can read our full methodology for the investigation here.

Ten years of Duke and Ferrous

With its high concentration of iron, gold and gemstones, Brazil’s Iron Quadrangle has long been a lucrative region for mining. It falls within Minas Gerais, a southeastern state bordering Rio de Janeiro.

After Ferrous Resources was founded in 2007, it raised more than $1 billion with plans to build a pipeline to transport iron from its mines in the Quadrangle to Espírito Santo, a state along the Brazilian coastline. The following year, Ferrous bought land throughout Espírito Santo to build an iron processing plant and a port to export processed materials to China.

Environmental impact studies raised concerns about the pipeline’s proximity to the San Bartolomeu River, a key water source for communities along its path. The river supplied water to over half of the city of Viçosa, and was the only water source for the Federal University of Viçosa.

One study notes that in a region already experiencing severe water shortages, the operation posed a potential threat to clean drinking water for more than 110,000 Brazilians, many of whom were rural farmers. Locals also voiced concerns about increased erosion and deforestation in the region.

Duke bought more than 1.7 million shares in the company in 2008, valued at $10 million.

The University maintained its investments in Ferrous amid the company’s alleged participation in an illegal land sale scheme organized by government officials: a Brazilian police report states that Ferrous appeared to be nothing other than a “front company” for an operation in which it allegedly bought land at artificially high prices from businesses owned by public officials in exchange for major tax incentives. The scheme allegedly diverted $13 million from the city of Presidente Kennedy to the officials who orchestrated it.

Officials at Ferrous did not deny that the company had been offered tax incentives, but said they were granted them for bringing business to the region, according to a letter to the Court of Justice of Espírito Santo that was obtained by the Brazilian newspaper Seculo Diario.

ZMM Empreendimentos e Participações Ltda., created less than a year before the series of sales, was one of the companies doling out land to Ferrous. It was partially owned by Marcos Antonio Vieira de Novaes, councilor and municipal secretary of planning of Presidente Kennedy.

BK Investments—one of ZMM’s partners—was owned in part by Jose Teofila de Oliveira, the state’s former secretary of finance.

In one sale, ZMM bought land and resold it to Ferrous just 25 days later at 150 times its initial value. In another series of transactions, ZMM bought land and resold it to Ferrous five days later at over 300 percent its original value.

When news of the investigation broke in 2012—the same year that protests about the potential environmental impacts of the pipeline reached a climax—the police arrested 28 people and issued 51 search and seizure warrants in connection with the scheme.

Meanwhile, back in Minas Gerais, over 100 people took to the streets to march against the operation. Following the demonstration, the City of Viçosa filed a motion to repudiate the pipeline. Ferrous halted its plans for the pipeline that same year, citing decreased momentum in the iron market.

In 2015, Duke bought an additional 1.9 million shares in Ferrous—valued at $300,000. The University’s holdings now stand at $1 million.

Vinicius Borges, a representative for the Court of Justice of Espírito Santo, wrote to The Chronicle in an email that the trial is still underway, with no “decisions or resolutions whatsoever.” He could not provide further comment on proceedings due to an order of secrecy by the case judge.

Luciano Santos, general counsel for Ferrous, declined to comment on the company’s entanglement in the ongoing lawsuit when reached by phone Tuesday.

Schoenfeld, Baxter and Triplett declined to comment on whether they or other administrators were aware of the company’s entanglement in the ongoing lawsuit.

Pending approval by Brazilian regulatory authorities, Ferrous will be acquired by Vale—one of the world’s largest mining corporations. In an email to The Chronicle, a representative of Vale declined to comment on Ferrous’ involvement in the alleged land sale scheme, writing that it is still an “independent company with its own management.”

Although Schoenfeld said it is against University policy to comment on specific investments, he provided The Chronicle with the value of Duke’s holdings after he was presented the findings of its investigation.

“The university does consider investments of the endowment to be something that reflects the values of the institution,” Schoenfeld said.

Inside Duke’s investment process

With its $8.5 billion endowment at a record high, Duke is among the wealthiest 15 schools in the United States.

The University manages its investment portfolio through two groups: The Duke Management Company, or DUMAC, and Gothic Corporation—a wholly owned subsidiary of DUMAC. In 2016, Gothic managed $6.9 billion of the University’s then $7.9 billion endowment.

“The purpose of the endowment is not to make money,” Schoenfeld said. “The goal of the endowment is to ensure a permanent level of support and that gets done in a variety of ways.”

As of the end of fiscal year 2017, Duke held a total of $13.8 billion in investments.

Gothic doesn’t make its own investment decisions independent of DUMAC, according to Schoenfeld. In fact, they share the same president—Neil Triplett, a former hedge fund manager—as well as the same treasurer, David Shumate. Both are nonprofits overseen by an Board of Trustees for investments as well as the University’s Board of Trustees.

The primary reason for splitting funds between the groups is investment utility, Schoenfeld said.

“Much as you would with your retirement account or your personal investments, you would not have all of your money in a pillow on your bed, so there are a lot of different investment vehicles that DUMAC uses,” Schoenfeld said.

Although DUMAC and Gothic may not always invest in the same entities, both groups bought shares in Ferrous in 2008. Furthermore, they both increased their holdings in 2015. The only difference is that Gothic bought shares in Ferrous directly, while DUMAC bought shares through Bank of New York Mellon, according to share receipts and shareholder lists.

As a private university, Duke does not have to disclose its investments to the public beyond its tax returns. Some information about where Duke invests is detailed in these Form 990s, which is the tax return form that Gothic and DUMAC file with the Internal Revenue Service. But the IRS only requires summaries of investments—-not line items—-and the University’s practice of investing through blocker corporations obscures the true recipient of those funds.

“It is the longstanding university policy that the university doesn’t disclose or comment on individual investments,” Schoenfeld said. “That’s as much a competitive matter of endowment management as being able to make multiple investment decisions that require some level of confidentiality in order for the University to have access to those kinds of investments.”

Blocker corporations are companies located in tax havens, or countries with laws that allow investors to pay low taxes on large sums of cash. Some companies establish headquarters in tax havens to save cash, while carrying out operations elsewhere.

Ferrous is a good example of a blocker: Despite operating in Brazil, it is based in the Isle of Man—a small island located between Ireland and England. The Isle of Man has a 0 percent corporate tax rate.

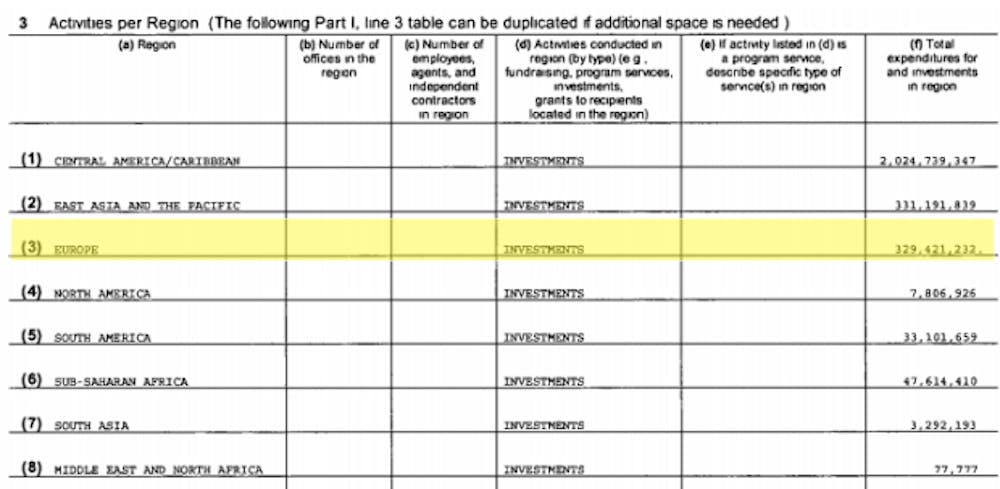

And since the IRS only requires that nonprofits report the location of the headquarters of its investments, Gothic and DUMAC’s holdings in Ferrous are listed under Europe—-not South America.

“The 990 is not necessarily designed to make everything transparent,” said Richard Schmalbeck, Simpson Thacher and Bartlett Professor of Law. “There’s a compromise between the interests of transparency and the interests of readable information. If you’re looking at an organization like Duke, with an $8 billion endowment, the 990 would be the size of a telephone book.”

There is also nothing inherently nefarious about blocker corporations, said Schmalbeck, who studies nonprofit tax law. He described Duke’s involvement with blocker corporations as an avenue to maximize the return on its investments by avoiding a corporate income tax, similar to how hedge funds and wealthy individuals might invest their money.

‘This is not our burden to bear as students’

When members of the Duke community want to inquire about or make recommendations regarding investments, they must first submit a request to Advisory Committee on Investment Responsibility.

If the committee votes that the request is of significant interest to the University, they send the president a report. Then it’s up to the president to make a recommendation to the Board of Trustees, which might impose guidelines on DUMAC and Gothic.

The process is dependent on well-researched petitions, according to Baxter.

“We have no research office, we are not an ombudsman, and we do not conduct roving inquiries without some basis for believing that there is a matter that needs further discussion and investigation,” Baxter said.

Some students say that can be a major undertaking.

“It’s not fair to put that all on students,” said senior Ethan Miller, who works on the Duke Climate Coalition’s divestment campaign divestment team alongside Seaver Wang, a graduate student at Duke’s Cassar Lab.

Miller said he and Seaver spent over 120 hours researching and writing three memoranda focused on Duke’s divestment from fossil fuels and proving that DCC met all the requirements to propose decarbonizing the endowment before their labor paid off.

“It was like no transparency,” Miller said. “They didn’t give us any numbers, and they didn’t give us any names. They were kind of just listening and giving their feedback, but they weren’t doing any work on their side.”

Responses to questions about the value of Duke’s holdings are generally limited by the University’s guidelines to keep detailed investment information private. Miller said that at first, ACIR only gave him and his colleagues “ideas” of how much Duke invested in Carbon 200 companies. The list is comprised of the top public fossil fuel companies, according to Fossil Free Indexes.

In December, Miller and Seaver’s work paid off. The duo, along with two other members of DCC, signed non-disclosure agreements to gain access to detailed information about Duke’s investments. They now participate on a subcommittee that focuses on divesting from companies in the Carbon 200.

“That’s not to say that it hasn’t taken away from us doing classwork at times,” Miller noted. “This is not our burden to bear as students. Duke and ACIR were not fulfilling their job in doing all the research and work to invest environmentally responsibly. We should be able to do all our classwork and push Duke to be more environmentally friendly. It’s not fair to have to weigh those two options. ”

Although Miller and ACIR are still limited by what information DUMAC is willing to share, he said they are currently developing a proposal to bring to President Vincent Price about divesting from fossil fuels. Miller added that since signing the NDA, members of ACIR have been helpful.

If the Board of the Trustees takes action on inquiries or suggestions, the results are publicized. That last happened in 2012, when Duke adopted investment guidelines on conflict minerals following student pushback.

With regards to the inquiry process, Schoenfeld acknowledged that students and the administration may not agree on the results, but said that Duke’s process is on par with peer institutions and “balances the needs and demands of a complex investment vehicle with the goals and the interests and the input of multiple stakeholders within the University.”

Duke students fighting for increased transparency around investments are not alone. Following the Paradise Papers, undergraduates at Stanford University also voiced concerns about the school’s lack of clarity on how it invests its endowment.

At Columbia University, which held more than eight million shares in Ferrous, it is also against school policy to comment on specific investments. Although the university divested from private prisons and thermal coal, some students worried that it could be investing indirectly through blocker corporations or hedge funds.

With 15 percent of higher education institutions holding 74 percent of the wealth, the policies established to maintain a competitive edge among a small pool of schools also makes tracking those investments difficult.

When navigating the opaque world of blocker corporations and multibillion dollar investment funds, high-risk document leaks like the Paradise Papers shed a rare light on where the investments of elite universities end up.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.