Migrants on rickety rafts in the Mediterranean Sea face a potential "graveyard."

So co-directors of Duke’s Social Movements Lab bought a boat in order to rescue them.

In 2016, Italy saw a record number of asylum seekers by boat. However, overpacked ships have flipped and capsized in torrid waves and frequently have been unable to send distress signals, meaning that many accidents have turned catastrophic. With migrants continuing to arrive, the yearly death count had reached 1,600 by September 2018, according to the according to the United Nations Refugee Agency.

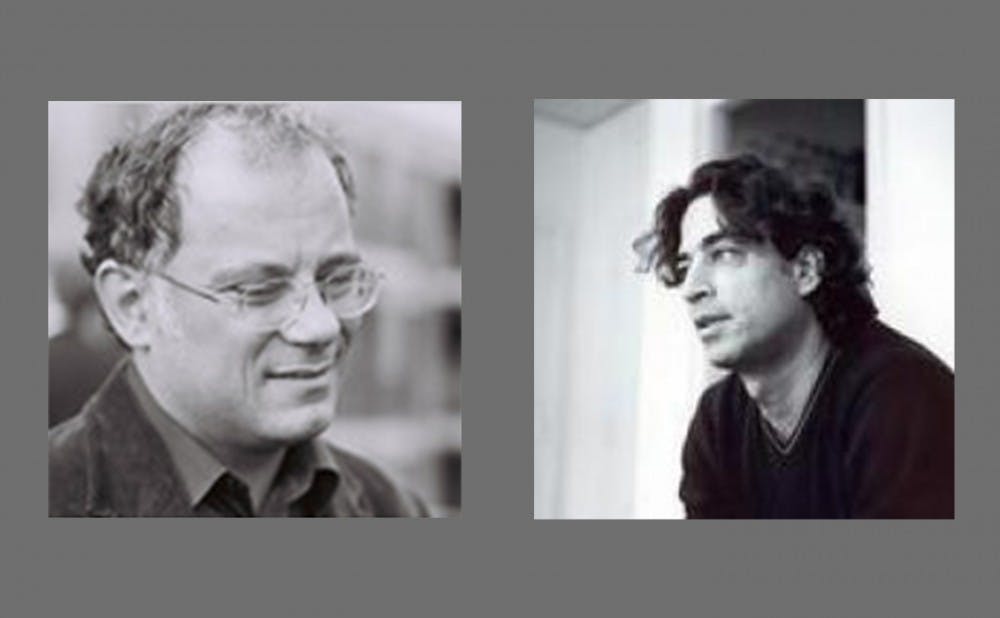

“The Mediterranean has become a graveyard,” said Michael Hardt, professor of literature and co-director of the Social Movements lab .

Along with a group of friends and Sandro Mezzadra, fellow co-director of the lab and a political theorist at the University of Bologna in Italy, Hardt is a part of a larger project called Mediterranea, which is a coalition committed to raising awareness in Italy.

They got a loan, gathered money and purchased an Italian boat named Mare Jonio for 400,000 Euros. Boats carrying an Italian flag cannot be legally turned away, allowing them to conduct rescue missions in partnership with non-governmental organizations (NGOs).

“We wanted to do something beyond resistance, something positive and unexpected,” Mezzadra said.

Even when migrants were able to ask for help, they faced hostile laws and restrictions. Governments like Italy had stopped saving boats in distress.

Instead of discouragement, Hardt and Mezzadra saw an opportunity.

Their efforts did not come with obstacles, however. At the start, Mezzadra and Hardt “had no experience about buying a ship." There were a multitude of regulation minutiae and technicalities that they only were able to navigate with help from NGOs.

“We had some kind of virtù but we also had quite a lot of fortuna,” Mezzadra said.

They tried to pressure the Italian government into action and show migrants much differently than the stereotypes and images propagated by hostile governments.

“A ship is a ship, a project is a project," he said. "We cannot overestimate the impact of that."

Following some pressure, the Italian government returned to saving migrants.

The group's ship has not yet rescued any migrants. Whenever their ship responded to distress calls, the Italian government saved migrants.

In October, the Italian government had rescued a rubber raft of 70 migrants off the coast of Malta, only acting once the Mare Jonio had set sail. The Italian and Maltese government had been locked in stalemate, both insisting that the raft was in each other’s waters.

“Apparently, the Italian government wants to make sure that our ship does not rescue migrants," Hardt said.

Mediterranea’s project has resonated with people from all over the world—its Mediterranea’s crowd funding page has raised more than half of its 700,000 euro goal.

As the boat traveled and met union organizers, shipping brokers, ship owners, naval architects and engineers, Mezzadra discovered support often greater than their official duty. The way the Italian government had violated “the law of the sea”, the unwritten rule to help people in distress, had sat uncomfortably with many.

“People quite far from our world, who at the beginning must have considered us kind of crazy,” Mezzadra said.

Hardt hopes that the impact of his project does not stop in Italy.

“People should organize against such injustices in any way they can," Hardt said. "For us, this project is particularly important to demonstrate that even in difficult times like today, when the political forces against us seem to be extremely powerful, we can still organize and act effectively."

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.