During his speech at the National Prayer Breakfast in early February, President Donald Trump said he would "destroy" limitations on churches' political activity.

Passed in 1954, the Johnson Amendment prohibits churches and other organizations that hold 501(c)(3) tax-exempt status from endorsing political candidates, although they can participate in voter education and register voters. Repealing this limit was one of Trump's campaign promises, and it was welcomed with applause at the breakfast.

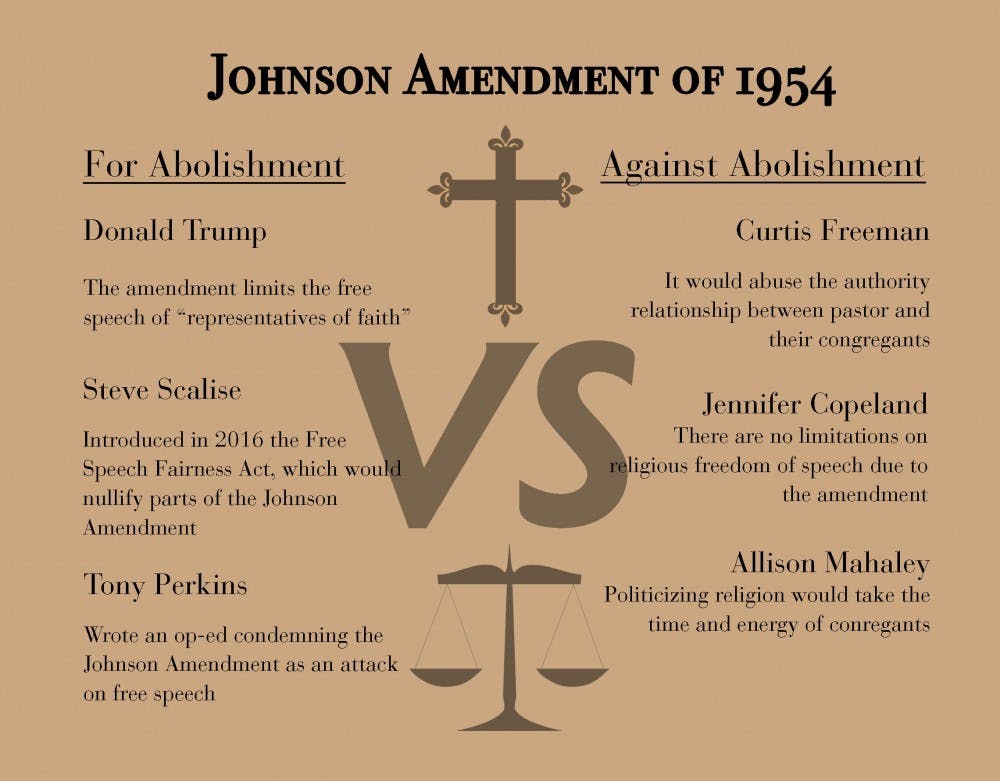

“I will get rid of, and totally destroy, the Johnson Amendment and allow our representatives of faith to speak freely and without fear of retribution,” he said.

Trump said that the amendment restricts the free speech of “representatives of faith.” However, Jennifer Copeland, executive director of the North Carolina Council of Churches and former United Methodist chaplain at Duke, disagreed. She said that there are no limitations on religious freedom of speech due to the amendment.

“Any church or nonprofit that wants to come out in support of a candidate can. They will just lose their tax-exempt status,” she said. “If I want to support a candidate for president, or for mayor for that matter, I can do that and my organization can do that. But now when you contribute money to me, your contribution is no longer tax-free.”

Although only one church has ever lost its funding due to the Johnson Amendment, Curtis Freeman, research professor of theology and Baptist studies, said the law exists largely as a threat to churches to stay away from partisan politics.

Some experts said that if Trump carries out his promise of getting rid of the law, the results may not be what he expects. Mark Chaves, professor of sociology, religious studies and divinity, explained that repealing the law would help Democrats more than it would Republicans.

“There’s an irony here—the reason that conservatives are pushing this is because they think the most politically active churches are white evangelicals, but in fact the most politically active churches are black churches,” he said. “If they do rescind this rule, it might well be that it energizes more on the Democratic politics side.”

Allison Mahaley, president of the Orange Durham Chapter of Americans United for Separation of Church and State, said that politicizing religion would take the time and energy of congregants, who are busy enough with their current work.

Freeman also raised theological issues with Trump’s proposal, saying that it would abuse the authority relationship between pastors and their congregants.

“With all the things that churches do to provide community and bring people together, this would create a wedge in every denomination and every church,” Mahaley said.

Copeland and Chaves both noted the chief issue with Trump’s proposal is that other groups might exploit churches' tax-exempt status. Political groups would rush to funnel political money into churches for this reason, Chaves suggested.

Freeman said he sees it as a “civic responsibility” of churches to not be politically partisan since they do not have to pay taxes.

“The funny thing about it is that churches get tax-exempt status, but if the church building burns, what do they do? They call the fire department,” he said. “They have city services, like electricity, water, all these things. They don’t pay any taxes, like tax-paying citizens do, for municipal things.”

Some groups, however, do support Trump’s promise. Tony Perkins, president of the Family Research Council, penned an op-ed in Religion News Service that condemns the Johnson Amendment as an attack on free speech.

“This overly broad muzzling has included comments of pastors speaking from the pulpit about candidates as well as policy matters,” he wrote. “Simply put, the Johnson Amendment has been used to censor speech—something that should never have occurred.”

Representative Steve Scalise of Louisiana, a Republican, introduced in 2016 the Free Speech Fairness Act, which would roll back parts of the Johnson Amendment. Trump has not yet taken any action to fulfill his promise to “destroy” the amendment.

“There hasn’t been a repeal motion yet,” Copeland said. “If that were to happen, we would mobilize in high gear and advocate on behalf of retaining the amendment.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Bre is a senior political science major from South Carolina, and she is the current video editor, special projects editor and recruitment chair for The Chronicle. She is also an associate photography editor and an investigations editor. Previously, she was the editor-in-chief and local and national news department head.

Twitter: @brebradham

Email: breanna.bradham@duke.edu