In 1968, writer James Baldwin appeared on “The Dick Cavett Show” and offered an explanation of a racial paradox which he understood to pervade American society: “When any white man in the world says, ‘Give me liberty or give me death,’ the entire white world applauds. When a black man says exactly the same thing, word for word, he is judged a criminal and treated like one.”

Nearly 50 years later, Baldwin’s sentiments are remarkably relevant, perhaps to a worrisome degree. Such a quote could easily be attributed to a Black Lives Matter activist, railing against police brutality and the relentless killings of unarmed black citizens. It’s clear, then, why director Raoul Peck decided to use Baldwin as the subject for his latest documentary “I Am Not Your Negro,” which forcefully examines race relations and blackness in America. Baldwin’s mediations on race are timeless, but it’s because of this endurance that they are jarring, visceral insights into the stagnation that burdens race relations in America today. In “I Am Not Your Negro,” Peck asks us: How can Baldwin’s words hold such weight nearly half a century later? How, exactly, did we fail black communities in the meantime–and why?

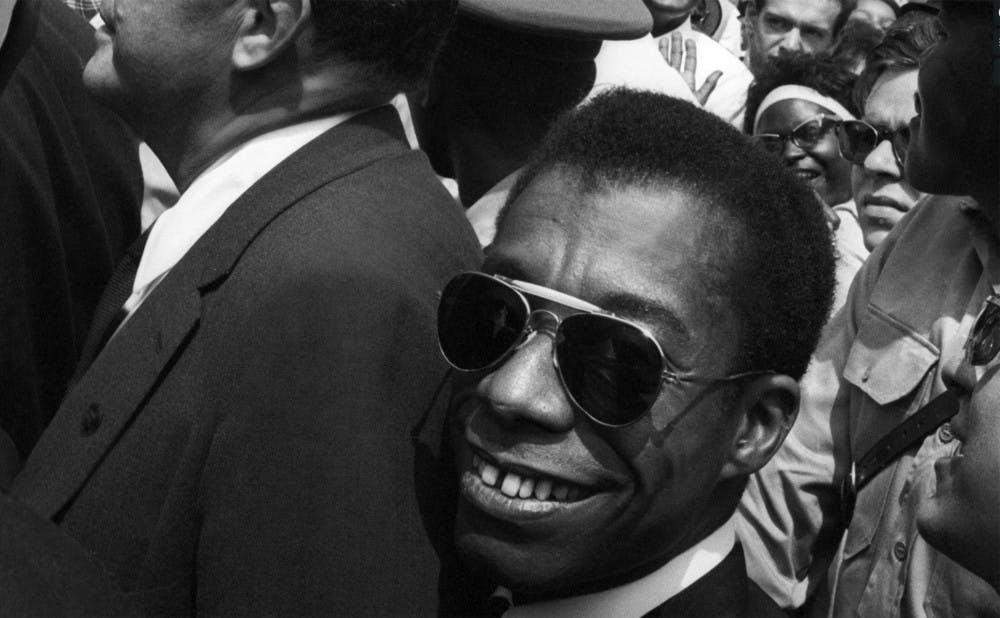

The documentary is based on Baldwin’s unfinished manuscript “Remember This House,” which was a semi-autobiographical profile of Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, and Medgar Evers–three assassinated civil rights leaders with whom Baldwin had personal relationships. “I Am Not Your Negro” allows Baldwin’s words to tell the film’s story, through both his writing (narrated by Samuel L. Jackson) and found footage clips of various interviews and speeches. Peck intertwines Baldwin’s musings with clips and images from touchstones of America’s racial landscape, from the Civil Rights Movement to the terse face-off between civilians and police officers in Ferguson.

Although Peck makes his intentions undeniably clear by juxtaposing such images of current and past racism, Baldwin’s incendiary comments on blackness and oppression are the clearest indicator of such a connection. Baldwin didn’t know that Barack Obama would be elected president, that white nationalism would have a vigorous resurrection, that the Black Lives Matter movement would become as wide-spread as it did. But when he said that “to be a Negro in this country and to be relatively conscious is to be in a rage almost all the time,” Baldwin indicated a deep understanding for the anti-blackness that is deeply rooted in our country, and the lengths to which white people will go to in attempting to deny it. Follow this statement with an image of a young black man shouting at a white police officer, and Peck’s message is self-evident: if you do not understand why such an assertion remains true to this day, you have not been paying attention.

Baldwin’s words are written in his sharp and poetic tongue, but they’re also tinged with a modicum of insecurity and weariness. He was, after all, not an activist on the front lines like Malcolm X or MLK Jr., but a writer whose blackness was both formative and inescapable. “I Am Not Your Negro” witnesses him debating with white scholars at Cambridge University and explaining his views to white talk show hosts, but there’s always the indication that Baldwin was exhausted. Tired, perhaps, of uttering his grievances with whiteness only to be met with blank stares, of having to constantly engage with his blackness and speak for his race a whole. This, we are reminded, is a burden that white folks do not bear–the power of whiteness is the power of ignorance, the ability to not think critically about race and not confront the failings of our institutions and behaviors.

Ostensibly, “I Am Not Your Negro” is a documentary about race and racial inequalities in America, told through Baldwin’s unfinished manuscripts about civil rights leaders and his commentaries on blackness and racism. But it’s still about James Baldwin, a gay black writer from Harlem, more than anything else–unavoidable, given that the film is so deeply imbued in his words and his image. It’s within Peck’s erasure of Baldwin’s homosexuality that his documentary falters. Peck shoehorns Baldwin into a certain narrative, ignorant of the intersections of the writer’s life which affected him as deeply as his race.

Choosing Samuel L. Jackson to narrate Baldwin’s writing is indeed the largest shortcoming of Peck’s film. Jackson’s voice is low and gravelly, a deeply masculine and firm growl which has no similarities to Baldwin’s lilting cadence, accented and lisping throughout his interviews and speeches. If Peck wanted to explore how America has failed its black communities in its lack of growth and progress, then he, too, has contributed to the current inability to recognize the fierce intersections which create unparalleled experiences of oppression for men like Baldwin.

Though it may not be a radical documentary, “I Am Not Your Negro” is a tremendously compelling and emotional outpouring of blackness and American racial attitudes, ensnared by the intelligence and passion of James Baldwin. It’s not a historical examination of race–if you’re looking for that, Ava Duvernay’s “13th” might be more appropriate–but it’s certainly an intimate one, guaranteed to stir every viewer in a deeply personal way.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.