Lobbyists on Capitol Hill are typically associated with political groups and big businesses, but Duke has its own lobbyists who fight for the University’s interests.

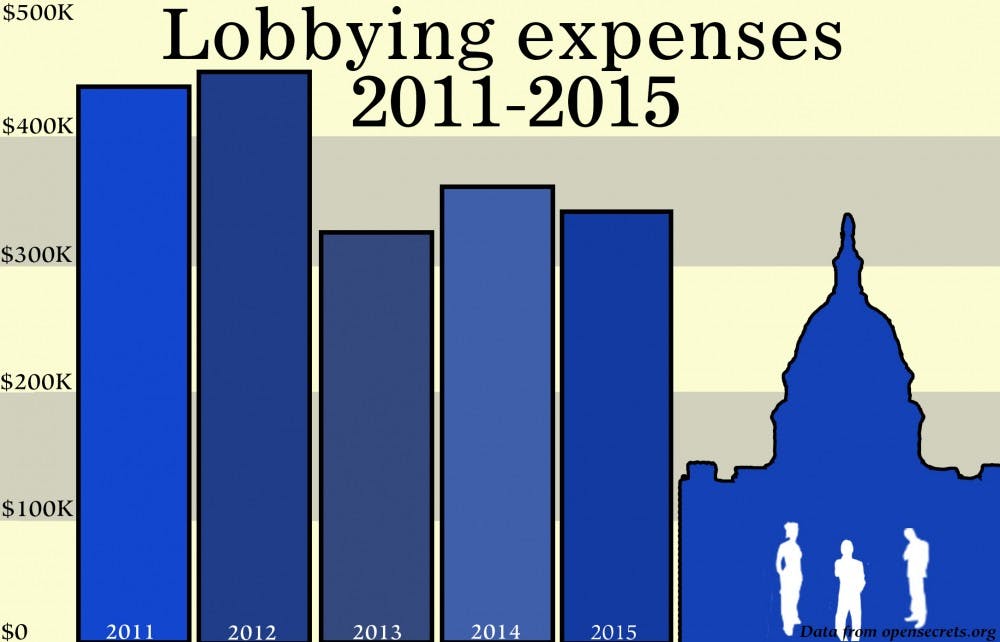

Last year, the University, including its Health System, spent $362,542 in lobbying expenses at the federal level—ranking 44th in dollars spent in the education industry—according to the Center for Responsive Politics. On the state level in 2014, Duke spent $9,906.63 in lobbying expenses, according to University disclosures to the North Carolina Secretary of State’s Office. Much of these lobbying expenditures are spent advocating for the University’s diverse interests, including student aid, Medicare and Medicaid reimbursements, research funding and the DREAM Act.

“You would be hard pressed to find anything on campus that wasn’t in some way affected by federal policy or politics,” said Michael Schoenfeld, vice president for public affairs and government relations. “If you pick anything that’s going on in Washington today, we can draw a line to Duke.”

Duke’s lobbying expenditures—which Schoenfeld referred to as a “microscopic” part of the University’s overall budget—are similar to some of its peer institutions. The University of Chicago spent $369,223 last year, and the University of North Carolina spent $349,296, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. Lobbying expenditures vary widely from university to university, however. The University of Pennsylvania reported spending $850,000 on lobbying in 2014, while Emory University reported spending only $195,000.

Institutions like Duke are typically more conservative in how much they spend due to their already privileged status, said Michael Munger, director of the Philosophy, Politics and Economics program.

Duke and its peer institutions are prohibited by law from making campaign contributions, forming political action committees, expressly advocating for any candidate or political party and engaging in partisan activity, said Christopher Simmons, associate vice president of federal relations.

While the public often has a negative perception of lobbying, Melissa Vetterkind, director of the office of federal relations, said that the type of lobbying Duke does is different.

“The vast majority of what we do is more educational versus active lobbying,” Vetterkind said. “We’re telling the story of what federal research dollars mean to Duke and how Duke uses it and puts it out to general society.”

Duke in Washington

Simmons and Vetterkind are Duke’s only two registered lobbyists—defined as spending more than 20 percent of working hours on lobbying work within a three month period—at the federal level.

The University focuses its lobbying on issues that have a direct impact on the University, its faculty and its students.

In particular, research funded by federal agencies—such as the National Institutes of Health and National Science Foundation—is a priority for the University. In 2013, 35 percent of the money Duke received in federal revenue came from research awards, per the Office of Federal Relations’ website.

Simmons explained that Duke gets access to research funding by having faculty go through a peer review of their project proposals by the award-granting agency in question. Each agency is, in its budget, appropriated a certain amount of money that it can dole out to research proposals. Duke’s goal is to increase the size of that overall pot in order to give faculty more opportunities.

One way Duke does this is by encouraging faculty and administrators to testify in front of Congress on the importance of research to universities, Simmons wrote in an email.

As such, fluctuations in the University’s research funding depend more on faculty competitiveness across universities than they do on decisions made in Washington, Simmons noted, adding that a decrease in the overall pot need not imply a decrease in the amount Duke receives.

Duke’s awards from the NIH—one of Duke’s top providers—have remained relatively stable since 2012 despite five percent cuts in the NIH budget in 2013 due to budget sequestration, falling from $392 million in 2012 to $363 million in 2013 before rebounding to $383 million in 2014.

Munger noted that, for the most part, universities like Duke lobby in order to prevent threats from “budget hawks” to cut research funding from reaching fruition rather than advocating for increases.

One potential exception to that rule, however, is the 21st Century Cures Act—which Simmons said Duke has actively weighed in on—that just passed the House of Representatives and is pending confirmation in the Senate. If it passes, the bill will increase NIH funding to $8.75 billion over five years starting in 2016.

Duke has seen cuts in funding due to budget cuts on Capitol Hill. For example, in 2011, the University saw significant cuts to its foreign language and international studies programs due to budget reductions in Title VI of the Higher Education Act.

Simmons explained that the act is supposed to be reauthorized every six years and that Duke will be closely following current debates over the reauthorization in Congress.

Another piece of legislation Duke has actively lobbied for is the DREAM Act, which—if ever passed—would offer undocumented students in college a pathway to legal status.

While acknowledging that support for such proposals is a divisive issue in the current political climate and potentially amongst Duke faculty and students, Simmons said that the legislation had a direct impact on Duke. For instance, undocumented students who might want to be able to study abroad or participate in other activities would be unable because of the lack of legal documentation.

DUHS and State Level

Although DUHS’ lobbying expenses are reported along with those of the rest of the University, a separate office from the Office of Federal Relations manages DUHS’ efforts—the DUHS Office of Government Relations.

Paul Vick, associate vice president for government relations at Duke Medicine, oversees both DUHS’ lobbying efforts as well as all of the entire University’s state-level lobbying. The University has one registered state lobbyist—Doug Heron, assistant vice president for government relations at Duke Medicine.

One of DUHS’ main concerns at the federal level is Medicare, Vick said, noting that any reduction in Medicare funding means DUHS gets less reimbursement for its Medicare patients. Health reimbursements made up 64 percent of Duke’s total revenue in 2013 according to the Office of Federal Relations website.

At the state level, DUHS is engaged with potentially imminent changes to North Carolina’s Medicaid system that would take the State’s Medicaid program from a “fee-for-service” program to a “managed care” system—where a specific amount of money in reimbursements would be allocated for any given patient.

Vick added that DUHS isn’t lobbying for or against the change, but rather to ensure that the final legislation allows Duke Medicine to continue to provide quality patient care.

Another big potential change that would affect the University regards tax policy. As a nonprofit, Duke is eligible to get refunds on its sales tax payments, Vick explained, adding that the N.C. Senate is currently considering proposals to phase that program out.

Vick confirmed via email that DUHS is aggressively lobbying against the proposed change, because it would cost an estimated $40 million split evenly between DUHS and the University.

2016

Entering an election year, the procedures for University lobbyists on Capitol Hill do not change, in large part because Duke is prohibited from making campaign contributions, Simmons said.

Schoenfeld added that issues Duke cares about are expected to play a large role in the candidates’ platforms, namely student aid.

Candidates have already begun unveiling their plans for lowering college debt. Hillary Clinton and Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders recently proposed their New College Compact and College For All Act, respectively, which both aim to cut college costs for students. Ohio Governor John Kasich and Florida Senator Marco Rubio have also discussed ideas for student aid reform.

Simmons wrote in an email that Duke has historically supported student aid proposals that lower interest rates, simplify repayment plans and allow for refinancing loans at lower rates.

“The fact that we can’t make campaign contributions or endorse candidates doesn’t mean that we can’t meet with people to advocate for our issues and our interests,” Schoenfeld said. “We’re going to continue to be very active in telling Duke’s story.”

Editor’s Note: The Chronicle spoke with Simmons in person and by email, and with Vick by phone and by email.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.