On the first Friday of September, a family of three stroll into a rather unusual place. An extravagant clutter of odds and ends, the place houses dishes and fabric and lamps and, what is most interesting to two-year-old Katiya, toys. Toys line the counters on either side of an oblong room with board games stacked on one side and doll houses and plastic gadgets scattered on the other. In the middle of the room is a huge tub the length and width of a large desk filled to the rim with trinkets. This was Katiya’s first stop.

I met Katiya when she peeked out from a small crawl space under the huge tub which she had claimed as her nook. She looked up at me without saying a word but seemed to ask, “Dontcha wanna see what’s down here?” in that expectant way kids can look at you. I obliged and crouched down to have a look. Bathed in blue decorative lighting, barefoot and dressed in a one-piece floral dress, she looked like an exotic baby princess. She had placed her subjects gathered from the toy tub lined up on the soft cushions in her nook and picked each one up to present to me—several fragments of shells, a couple dolls that were neither fully dressed nor fully limbed and a plastic green frog she had named, appropriately, Frog.

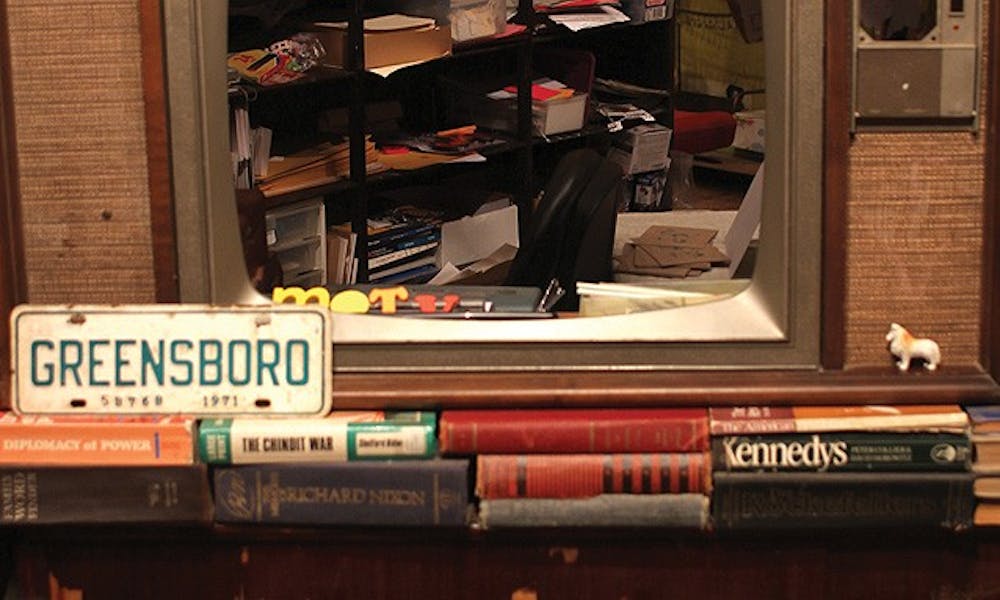

Katiya’s subjects are members of a larger collection of American merchandise and textiles that comprise the raw material and creative medium of Elsewhere, an exhibit in Greensboro, North Carolina that centers on this hoard of stuff that is housed in the building. This collection was accumulated largely by Sylvia Gray, grandmother of current Co-director George Scheer. Gray ran a store in this downtown Greensboro space from the late 1930s until 1997. As the business changed forms over the years, fabrics, ribbon cuttings, furniture and buttons, among other things, stocked up. Later on, Gray collected thrift and vintage items to sell and amassed random knick-knacks like toys, books, dolls, vinyl, suitcases, dishes, wigs and lamps. Eventually, she was collecting more than she was selling, and by the time she passed away, she had gathered this random inventory of everyday American material culture.

“We used to find a lot of mismatches,” Scheer remembered of sifting through the collection as he and his Co-director, Stephanie Sherman, and some of their friends transformed the store into an exhibit. “Cups that were printed wrong or strange anomalies in the production process. We’d find a bunch of really weird things that were like, this would be normal but the words are backwards on this mug.”

Scheer and his friends re-discovered this hoard on a whim in 2003 during a spring break trip when they decided to stop by Greensboro to see the old store George had told them about. In sifting through the massive amounts of objects they saw potential for it to become “a creative playground.” Drawing inspiration from a background in literature and writing, Scheer and his friends hoped to found a creative community that worked within the set of Gray’s collection by moving, sorting, ordering and rearranging the objects. They established Elsewhere as a nonprofit in 2004 and one year later launched an artist residency program, which attracts artists from all over the country for three to six-week tenures, to bring their vision to life. From these beginnings, Elsewhere has grown into one of the most significant exhibits in the Southeast, and it receives 400 to 500 applications for the residency program for every 35-50 available spots, Scheer said.

The Elsewhere exhibit is an eccentric space that defies standard labels. It is no longer a store because none of the items are for sale. It is also not a traditional art museum in the sense that pieces are presented to passive viewers. Elsewhere is somewhere between the two—something its directors like to call “a living museum.”

This living museum is essentially a hoarder’s attic but with high ceilings and interior decoration. Occupying two storefronts, Elsewhere is composed of two rooms jam-packed with odds and ends. One storefront has no glass and instead of the usual window display, there is a small elevated stage that showcases arranged furniture by day and serenading, folksy musicians by night. The huge, gaping window allows passersby a generous view of the exhibit, beckoning them to discover this cornucopia of stuff.

Just beyond the storefront stage, a guy wearing a light blue plaid shirt with a trimmed auburn beard stands behind a counter. This is very purposeful post for Chris Kennedy, the education director at Elsewhere. Visitors stroll into the exhibit with wonder and confusion on their faces, and he catches them before they wander in too far and explains what kind of space they are walking into. A little more enlightened and now equipped with brochures, these visitors are released to explore the hoarder’s shop.

Among the organized clutter are more intentional arrangements and pieces created by the artist residents. In the middle of the toy section is a display with an old, screen-less television set that people can crouch behind, pretending to be TV personalities. A couple structures, the size of telephone booths, are arranged in the back of the exhibit, one having the sign “Confess-a-torium” above it. In the adjoining room, there is a contraption called the Super Piano Bouncyball where drums, metal pans, a xylophone, a violin, an electric piano and other makeshift instruments are arranged or hung against a wall. The viewer, or musician in this case, grabs a handful of bouncy balls from a jar and throws them against this wall. The balls clang or ping off the instruments, creating a cacophony of sounds as they go scattering in all directions. Ah, art.

These interactive pieces are part of Elsewhere’s vision of being a creative playground. Artists engage visitors in the exhibit, and visitors are encouraged to pick things up, manipulate them, rearrange them and draw inspiration from them. They might see ordinary objects in a different light when they come upon a stone figurine of a Buddha sitting in the living room of a doll house. It can get the wheels turning, make them think—what can I make out of all of this stuff?

Those wheels were already turning for Katiya’s father, Ted Efremoff. He and his family had moved to Greensboro just a month earlier for him to take a position as an assistant professor of art at Greensboro College. Not long after arriving at the exhibit, Efremoff was already drawing artistic inspiration from the collection.

“I’m thinking of collaborating with this place,” he said. “They have this four person surrey—it’s like a beach surrey that people peddle—and I’d like to possibly use that for a project.”

[Folk Feng Shui]

Inspiration is not a one-way street at Elsewhere. Scheer and others promote a collaborative process among resident artists and between artists and the community. The exhibit is open from Wednesday to Saturday from 1 to 10 p.m. so that the community can see the artists at work and interact with them and with the exhibit. At one of the artist openings, held the first Friday of every month, Jess Hirsch, an M.F.A. sculpture student from Minnesota, set up shop for her Folk Feng Shui project. It involves rearranging people’s furniture into an art form—bringing energy and artistic value into someone’s home—and then putting it back to the original formation. Besides standard living rooms and bedrooms, she has also feng shui-ed cars, galleries and a foreclosed home.

“It’s really intimate to be invited into someone’s home and touch all of their possessions,” Hirsch said as she arranged the contents of someone’s purse in her open-house version of Folk Feng Shui, balancing ChapStick on a cell phone and draping a set of keys over both of them. “I like to get to know the person through the process and make it a positive experience for them.”

Jess said her residency at Elsewhere has changed her notions about domestic space.

“It’s really opened up my definition of what the home can be and what space you find attachment to. It doesn’t have to be the place you sleep. It can be the place where you work all the time and where you put your love and attention.”

[Super Wheeley Ball]

A loud siren blares from the adjacent room, jostling everyone’s attention. Jess breaks out into a grin and says, “You don’t want to miss that. It’s going to be really cool.”

This evening was the opening night of Super Wheeley Ball, a game one of the resident artists had created by tying two baskets sideways to a wheelchair-like contraption, and the siren indicated five minutes until game time. As people filtered into the adjoining room, the artist explained that the objective of the game was for each of two teams to throw a small, baseball-sized ball into their team’s basket as the facilitator pushed around the contraption trying to deflect their shots. When a player has a ball, he or she cannot move but can throw the ball to another player.

The players gathered around the contraption. There was Scheer in his Chucks and square-rimmed glasses along with two other artists on the red team. On the yellow team, there was Efremoff, who seemed to have already found his way into the artist community.

Another blare of the siren kicked off the game, and the facilitator, dressed in a yellow helmet and a white inspector body suit, threw one ball up into the air. Another artist at the organ began playing a funky, jolly tune as a frantic rush for the ball commenced. Another ball entered the fray and there was a sudden madness, with seven fully grown adults in a 10x10 space charging and ducking and blocking and leaping and running in circles. The balls bounced around into the Super Piano Bouncyball piece and also at one point behind the organ player, who kept playing unperturbed. It was a chaotic ordeal that concluded with a blow of the facilitator’s whistle when Scheer threw the ball into the basket in an acrobatic, leap-dive move.

In subsequent rounds, visitors at the exhibit mixed with Elsewhere staff and artists to play the game. None of them probably imagined when they made Friday night plans to attend an art exhibit that they would leap and laugh so much.

[The downtown community]

Scheer described the creation of Elsewhere as “an opportunity to consider thoughtful development in a town that was gentrifying and changing.” By inviting artists to Greensboro to become part of the social fabric, Scheer said, Elsewhere is helping to create a far more connected downtown. Artists are not just producing objects per se, but they are producing with a community, and through this interaction, Elsewhere provides a creative, collaborative impetus.

Only a month into their new life in Greensboro, Efremoff and his family seem to have molded naturally into the exhibit and the Elsewhere community. Katiya, crawling among the toys and rolling in the nook, was literally inhabiting the space, which her mother hoped to recreate for her at home. Efremoff, who was struck with an idea for an art project and a potential collaboration, ended the night as part of Elsewhere’s inaugural team of Super Wheeley Ball. It was just another Friday night, but all of these connections were made possible through the collection and the pieces that people created out of it.

“That’s the other really fun thing about Elsewhere,” Scheer commented. “Can you actually build an organization that is so flexible that it really engages the moment and the happenstance and the chance as significant parts of the experience?”

Efremoff would probably say that it can.

“I think it’s very visionary of the people who started this,” he said. “To see this collection and say, ‘This is a great resource and we should make a museum out of it—it’s inspiring.” p

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.