After significant decreases in National Institutes for Health funding, Duke professors are rallying for political support behind their research.

NIH funding has steadily decreased over the past several years, with especially steep cuts stemming from the 2013 sequester. As researchers find themselves feeling the funding cuts more deeply, some are turning directly to Congress—including four Duke professors who met with lawmakers two weeks ago as part of the Annual Rally for Medical Research Hill Day, which brought representatives of the medical community to Washington, D.C. But this trip to Washington was only one step of what could be a long battle, researchers said, emphasizing the importance of federal funding for their work.

“We want to send a clear message that medical research is of enormous value to the health and economy of our nation,” said Steven Patierno, deputy director of the Duke Cancer Institute and one of the faculty members who went to Capitol Hill. “Keeping people well allows them to be productive citizens, and research creates jobs. For every dollar invested into NIH research, there’s a minimum of a twofold return on investment.”

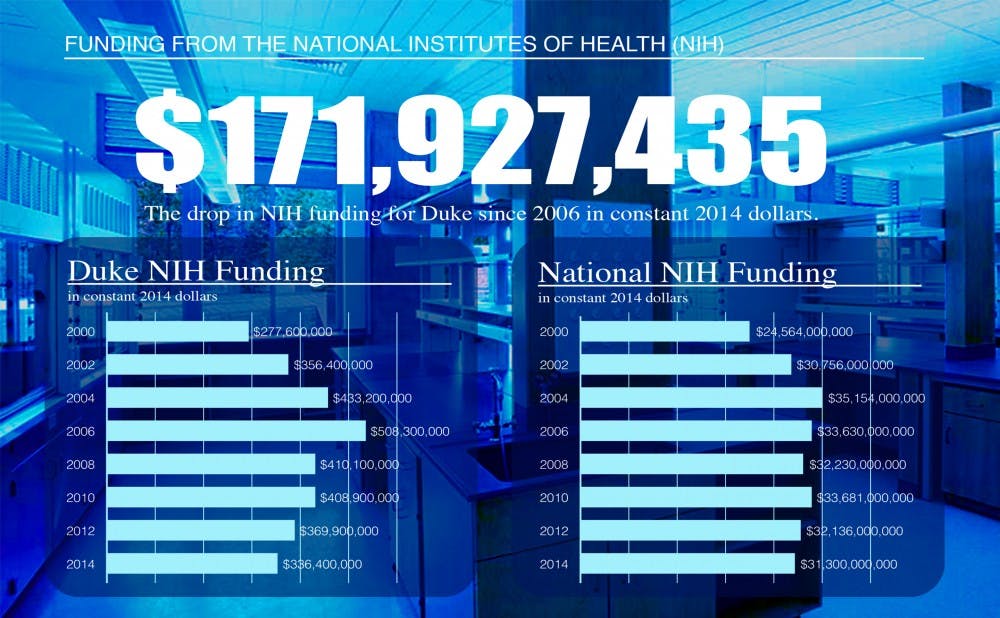

The NIH, which obtains its budget from Congress, has seen its funding slip since 2003—translating to a 20 percent loss of purchasing power, according to the nonpartisan Congressional Research Service. But even if funding levels were restored to previous levels tomorrow, it would take the research community 20 years to recover from the past decade, Patierno said.

“We’re stuck in this budget battle where many of us are left hanging and waiting,” said Raphael Valdivia, vice dean for basic science and one of the lobbyists. “So we’re pushing for a more stable funding stream because our concern for the future is that we’re going to lose our competitive advantage.”

The four Duke professors were joined on Capitol Hill by faculty from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Wake Forest University to meet with North Carolina's congressional delegation. The goal was not only to personally convey the importance of research, but to emphasize the significance research holds for the state’s economy, Valdivia said.

“We do have the power to do something about this,” Valdivia said. “Scientists in general tend to think the value of what we do is self-evident, but that’s not always the case. We need to be better at communicating with not only the public but those who control resources that we’re not just another expense.”

The faculty also wished to show the congressmen how the funding cuts have been affecting the next generation of scientists. With less money to go around, it has become increasingly difficult for graduate students and postdoctoral researchers to receive adequate training and get their own grants.

“Large numbers of very productive senior faculty who have been [at Duke] for years are now losing their grants – in many cases having to close up or scale down their laboratories,” Patierno said. “And even in the best of times, it’s very difficult for young students to get their first grant, so under the current situation it can be almost impossible.”

Patierno noted that fewer students are staying the course in the biomedical fields, with fewer undergraduates going to graduate school and fewer doctoral students pursuing careers in science. A reason for this, he said, could be the negative environment surrounding funding.

“They’re looking at their mentors and seeing what it’s like to struggle day after day, getting grant applications rejected again and again,” he explained. “We’ve already lost an entire generation of researchers and we’re in danger of losing another.”

The decrease in funding has also resulted in a significant drop in the numbers of grants awarded. Patierno said the financial cutbacks have resulted in a lack of sustainability of ongoing research, meaning many members of labs had to be laid off last year and a lot of projects had to be stalled.

“Excellent and outstanding grants aren’t even being funded anymore,” said Richard Brennan, professor of biochemistry and also among the four who went to Capitol Hill. “Younger faculty get their first grant now on average in their early 40s. In the long run we’re hurting our ability to do cutting edge research, while countries in Asia and Europe are quickly catching up to the U.S.”

Congressmen—and citizens, in general—may see the costs of funding research and not recognize the long-term investment that it represents, Brennan noted. But scientists are trying to show their representatives that the cuts could have an impact far deeper than what lawmakers see on the surface.

“I think it’s a very powerful message that Duke and UNC went together to the senators’ offices,” Patierno said. “If it’s possible for Duke and UNC to agree on something, then you guys can figure it out.”

The researchers hope that funding can eventually be restored to previous levels, which would be in the range of approximately $29 billion to $32 billion. At the least, the goal is a guarantee to match inflation in the upcoming years to minimize purchasing power losses, Brennan said.

“Everyone we met with is sympathetic towards us,” he added. “The battle doesn’t so much lie with their wanting to support us, so much as how they can actually do this as a divided Congress.”

Patierno noted that although there’s still a long road ahead to get Congress to agree on a budget, faculty members agree that direct dialogue with local and state representatives is crucial to solving the problem.

“We’re not just geeky scientists who stay in our labs holding pipettes,” Brennan said. “Biomedical research should be a priority in the U.S. We have tools and technology now that didn’t exist years before—we can make great advances now, but we can’t be held back by these funding issues.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.