Cassidy Curd is sitting on a swinging bench outside Bella Union, a coffee shop on Duke’s West Campus. It is 8:30 in the morning, and “Cass” has already finished lift, had coffee (iced, despite the cool air) and read several dozen pages of Sarah J. Maas’s “Crescent City,” which now rests on the table in front of her. She has piled her hair into a bun and put on a plain beige hoodie over her workout clothes. The only flashy things Cass wears are the gold rings on her fingers that match the long, ornate cross that hangs on a gold chain resting against her chest. She fiddles with it when she talks about God.

Cass is more used to throwing hardballs than receiving them — as one of the best pitchers in the country, it’s kind of her job — but she answers every tough question under a furrowed brow. She is standing, figuratively, on the precipice of her second season with Duke, one that carries with it the expectations set out for a sophomore who forced a no-hitter out of the third-seeded team in the ACC tournament her rookie year. But here, Cass is sitting, literally, on this blue-cushioned bench — which holds no expectations of her whatsoever — as she explains the origin of the seven tattoos she has inked across her body, seven testaments to the things Cass holds closest to her heart.

The funny thing is — Cassidy Curd does not have a softball tattoo.

A clock, ‘Vienna’ above it, right ankle

Softball, at this level, is about sacrifices. At home in Port St. Lucie, Fla., Cass’s high-school travel team meant missing weekends at the beach and skipping prom. In college, Duke’s third-ranked Division-I program coupled with its demanding academics means missing out on parties and sleeping in and watching basketball games.

That’s why the tattoo on her ankle — a reference to the Billy Joel song — is so important.

“A lot of the time I try to blow through life,” Cass admits. She’s trying not to do that so much. Slow down, you crazy child.

Sometimes it’s easier to count the minutes than to savor them. When Cass got to Duke in the fall of 2022, she kept to herself. The shock of college was too much. Then her long-distance boyfriend of two-and-a-half years cheated on her. She felt alone. She put up her guard. Her love of books became an easy excuse to self-isolate, to distract herself from the problem that had suddenly hit her like a softball to the head: Cass didn’t know who she was, besides a pitcher.

Charlie Densmore, Cass’s spiritual mentor, says pitching in softball “is one of the loneliest places in all of sports.”

Psalms 46:5, left arm

Cass met Densmore a few months into her freshman fall. A campus director for Duke Cru, a Christian ministry organization, he works directly with student-athletes. Her concerns were nothing out of the ordinary, for Densmore: Duke, with its demanding coursework and elite athletic programs full of other elite kids, is no easy place for athletes. But there was something unique about the way Cass opened up immediately.

“God is within her, she will not fall, God will be with her at the break of day” is Cass’s favorite Bible verse, which is why it’s tattooed on her arm. It’s almost like a motto. Densmore has a lot of his own mottos — “living life on life’s terms” being one of them. He doesn’t talk much about softball with Cass. He says there are more important things; the game is just their conduit.

Life at Duke got better for Cass after she began regular meetings with Densmore. She stopped self-isolating. Her faith got stronger, and her softball did, too.

“If I didn’t have him here … I would be in shambles,” she says.

Cass and Densmore know that there’s no way to “compartmentalize” different parts of a person. Maybe this is the hardest thing about being a student-athlete: If Cass has a bad day at school, she beats herself up, the same way she does if she stumbles on the softball field. There’s no way to separate the student from the athlete from the sister and daughter and friend. But at the same time, softball isn’t everything to Cass. It can’t be.

1975 (the year her parents were born), right shoulder

Twenty-year-old Makesha Holbrook put down her softball glove, hung up her No. 19 Nova Southeastern University jersey and never put it on again.

“You have to make a choice,” she recalls her chemistry professor telling her. “It’s medicine or softball.”

“I knew in the long run that softball wasn’t going to pay the bills,” Makesha says. “It was heartbreaking.”

She found solace in her kids, whose athletic careers she was able to live vicariously through. Makesha loves watching her daughter — who wears No. 19 just like she used to — on the mound; she says it’s Cass’ “comfort place.”

Mrs. Curd isn’t alone in watching. In 2022, 2.1 million viewers tuned in to the Women’s College World Series championship game, 200,000 more people than watched the men’s final. Things are different for women’s sports than they were when Makesha said goodbye to collegiate ball. But they’re not that different. Cass sees herself putting law school on hold for a few years to try her hand in the Women’s Professional Fastpitch league, which began play in 2023 and has four teams.

But softball won’t be forever, which is why it’s so hard, sometimes, to dedicate everything to the game. Why make all these sacrifices for something that will end in a few years?

Cass just loves it. She tries hard to remember that.

Picture John Curd, bald, strong (he’s a fire chief), the man who gave Cass her gray-green eyes and resounding voice, except his is laced more strongly with the South. He’s winding up to pitch. It’s a sunny Florida afternoon, and Cass’ eight-year-old brother TJ is stepping up to bat while Cass stands behind him, ready to catch her dad’s pitch. Makesha has first base loaded.

“When I want to go back to a simpler time, that’s what I think about,” Cass says.

Pie, left wrist

Cass is five, throwing a T-ball at her brother. In the field behind the Curds’ home, the whole family has gathered to play ball. At seven, TJ already has a killer swing. Cass decides she’s going to be better than her brother. She decides she’s going to play softball really, really well.

They both stick with the game. TJ commits to Florida for baseball in eighth grade. When he graduates high school, he’s ranked No. 3 in the state. When he’s in 10th grade, Cass commits to UCF, mostly to boast that she had committed earlier than her brother did.

Both their plans change: TJ ends up at Arizona and then Jacksonville, no longer playing baseball. Cass reroutes to Duke. Without baseball, TJ now has more time to be his little sister’s biggest cheerleader.

Somewhere in the midst of all this growing up, the siblings have a conversation about — well, pie, in Cass’ mind — but Pi, the Greek letter, in TJ’s. When Cass turns 18, she gets her pie tattoo, and TJ gets a Pi tattoo in the same spot on his wrist. The pies are perfect for their respective siblings: TJ, calculating, thoughtful, happy with numbers and the natural order of things; Cass, exuberant, sweet and shelled in a hard casing.

A sun and moon, upper left arm

In the spring, an old lady leans over the fence that separates the bleachers from the field at Duke Softball Stadium. Cass’s grandmother stares intently at the pitcher as her son-in-law hollers loudly from the stands behind her.

“My goal is to have a fraction of the heart that she has,” Cass says. She describes her mom’s mom as the kind of woman who “will give until there’s nothing left to give.”

Somewhere between schoolwork and softball and morning lift and Bible study and reading and relationships, Cass finds time for community service. She packs meals. She’s planning an event at the Duke Children’s Hospital for the whole softball team. When she’s home in Port St. Lucie, she coaches younger girls in softball, encouraging them to go after whatever they want.

Taylor Wilke, her hitting coach, has a clipboard covered in the handwritten notes on rainbow Post-Its Cass sticks on her desk every week.

Hi Co-Tay, I love you. What did the blanket say when it fell off the bed? So grateful to have you! You’re the best hitting coach I’ve ever had. I thought about this one all practice: What does a drummer name his two daughters?

It certainly seems like she has at least a fraction of her grandmother’s heart.

A small heart, top of her foot

Cass is seven, and she demands that her mother draw Taylor Swift’s tattoo on her foot after the one from the day before scrubbed off in the bathtub. Night after night, Makesha obliges, until the heart is not just a tribute to the singer but part of a mother-daughter routine. Eventually, Cass will have someone ink it permanently on her foot — one of her seven tattoos. Makesha will get a matching heart on her own foot.

This seven-year-old is the same Cass who piles into her parents’ bed after school and sports to read. Her nose is stuck in a book, then in another one. The reading doesn’t catch with her brother but it sticks with her, like it did with her mom.

At 20, Cass still hasn’t pulled away from the pages. She carries “Crescent City” — a fantasy novel at a monster 816 pages — to and from the women’s bathroom in Duke’s Keohane residence hall, putting it down only when she has to get in the shower.

“I can picture where I am in the book,” Cass says. “It’s a really nice place that I like to go to … takes my mind away from everything else going on in life.”

‘Defy all odds,’ ribcage

When Cass was 14 years old, she heard these words in a church sermon, and told her dad, “that’s what I want to do.”

In her year-and-a-half at Duke, Cass has certainly defied all odds: an All-American freshman team placement, All-ACC First Team spot, ACC Honor Roll and a conference semifinal no-hitter in her rookie season are just highlights. She became the first player in Duke history to have more than 100 strikeouts in her first season. She won the school Rookie of the Year Award. Duke made a limited edition t-shirt with “ALL CASS NO BRAKES” written on it, and sold it in the NIL store.

Now, things are harder. Cass still wants to “defy all odds,” but the odds have become more difficult to beat. There’s a lot of pressure. It’s mostly self-inflicted.

“She beats up herself very bad,” John says of his daughter. “She really wears a burden and really puts a lot of pressure on herself.”

Densmore says Cass is a “people pleaser.” She agrees.

“I get really hard on myself,” she says.

Coming back to school for her sophomore year was difficult. The fall meant long months of waiting for a season where Cass knew all eyes would be focused on her left hand.

But it also meant game nights at the house where the team’s seniors live, and trips to the mall with her teammates (who are her “friends first, teammates second”). Cass and her friends would leave the stadium on East Campus and pretend, for three hours, that they weren’t athletes. She would read at coffee shops, write poetry in her room before bed, agonize over the Contexto — an internet game the whole softball team plays, where you have to guess a random word — call her family, call her best friend Briana (her biggest “humbler”), force books on her mom and teammates.

“I want to be a NARP (non-athletic regular person) for, like, one semester,” Cass says. “I think I would have the time of my life.”

None of that, now. It’s spring again. Game on.

* * *

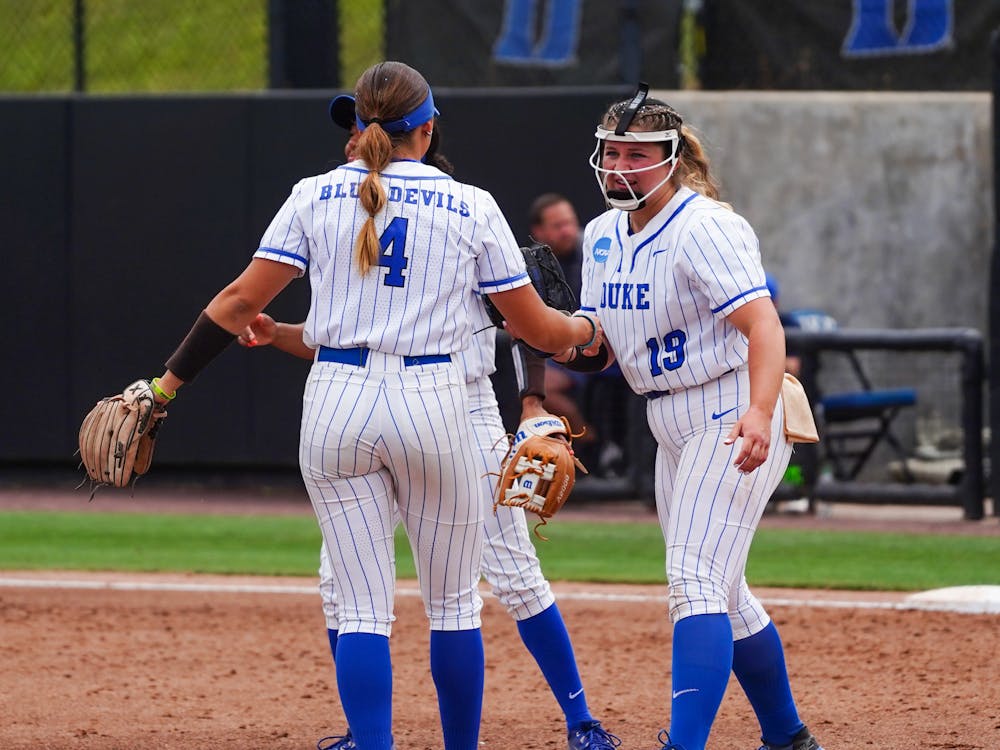

The season has begun with a bang — Duke is undefeated save for two losses, one to No. 1 Oklahoma and one to reigning ACC champion Florida State. On a late February day, Cass balances precariously on the backrest of a metal bench next to two of her four fellow pitchers. Her dirty-blonde hair is braided and twisted into a bun, like it always is on game days. She leans over the black fence surrounding the pitchers’ pen, watching a blowout game against Elon from this secluded back corner of the Duke Softball Stadium.

When the first inning rounds out, Cass hops off the bench and heads to the dugout, where the rest of the team is crowded. Duke leads 6-0. A smile lights up the sophomore’s face as she hugs Wilke from behind and hollers at the batters getting ready to swing.

Cass wanders around, picks up a Slim Jim, takes a bite — then winds up and pitches it away from the dugout with her left hand. She turns to her teammate.

“You like this stuff?”

Laughing, she cracks open a bag of Cheez-Its, takes a sip of a pink Spark energy drink (one of her NIL sponsors, the other one is Aquaphor) and turns her focus back to the game. The Blue Devils close the inning with another run and Cass leans her head back and yells: “Wooooooh!”

Her love of this sport, and what it has brought her, cuts through the air with her holler.

Cassidy Curd does not have a softball tattoo. She doesn't need one.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Sophie Levenson is a Trinity sophomore and a sports managing editor of The Chronicle's 120th volume.