The big secret about sex, Leo Bersani writes in his 1987 essay “Is the Rectum a Grave?,” is that most people don’t like it. And this is true, he says, even for those who seem most capable of embracing their own sexual impulses, including, say, the most enthusiastic proponents of polysexuality with multiple sex partners. In saying this, Bersani intimates that there is nothing more disorienting and boundary-breaking to our selves than the truth of our sexual desire. Or we can say with Bersani that desire disrupts and dissolves the coherence of any stable identity, causing the “shattering of the psychic structures themselves.”

What Amber Bain’s second studio album, “In the End It Always Does,” would have us confront is this messy and disorganizing force of desire. While the lead-off track “Spot Dog” limns the height of a loving relationship, modeled allusively on the throuple that Bain entered into during the pandemic lockdown, the rest of the album attests to the emotional turmoil of having these relationships come to an end. The transgressive and self-shattering desire evoked by loss and heartbreak – transgressive because Bain “know[s] [she] shouldn’t want it,” self-shattering because it “makes [her] wanna die every time” – makes its presence felt on “Touching Yourself,” for instance, as the wish to picture her ex-partner caressing herself, a wish whose blind insistence breaks down any defenses she attempts to conjure up.

“In the End” is, to be sure, an album about loss, despair, mourning and the frustration of failing to obtain one’s object of desire. But what is so distinctive about Bain’s production, in my opinion, is the playful exuberance with which she broaches the vicissitude of her desire. Notably, the use of the synthesizer on tracks such as “Over There,” “Boyhood” and “Sunshine Baby” not only serves as a welcome supplement to her laid-back and sultry vocal performance but, in virtue of its effervescence, also provides the somber and wistful lyrics with a much more nuanced affective tone. In these songs, Eric Mason has observed, “vocal hooks [take] a backseat to highly textured folktronica instrumentation and a more impressionistic rendering of desire.”

On this point, let us turn to my favorite track, “Sunshine Baby,” in which the wonderfully mournful hook – “I don’t know what’s right anymore/I don’t want to fight anymore” – is juxtaposed with zestful instrumentation as the song reaches its climax. The lyrics may labor to show us the way in which desire is, in Jamieson Webster’s words, “sometimes felt as a curse” because it disrupts our moral sense, but the thrust of the synth-laden instrumentation, performing a significant labor of its own, represents the ineffable pleasure-in-pain which renders this desire-as-curse itself desirable.

Here, the melody both literalizes and elicits what Bersani has called the “ecstatic suffering into which the human organism momentarily plunges when it is ‘pressed’ beyond a certain threshold of endurance.” And, as if to anticipate this climactic moment of catharsis in which sensory pleasure and self-shattering converge, Bain tells us to “hold on to this feeling ‘cause/you won’t feel it for long.” This is Amber Bain at her best: even as she fails to make good on her losses in and through “In the End,” her music is itself an aesthetic education in how to take pleasure in, rather than subdue, the unbearable desire incited by irremediable losses.

Another recurring theme of “In the End” is its meditation on the repetitiveness of desire, in the sense of returning to the same person and situation over and over again. On tracks such as “Morning Pages,” “Indexical reminder of a morning well spent,” and “One for sorrow, two for Joni Jones,” where acoustic guitar and piano take center stage and create a cozy, dreamy ambiance, we encounter, in ever-renewed forms, Bain’s candid admission and heartfelt acceptance of her inability to find anyone other than the person she has lost.

“But wait for a second, it always comes back to her/You always comes back to her:” we might hear, in this excerpt from “Morning Pages,” echos of Serge Leclair’s gloss on desire in his book “Psychanalyser” – that desire “aims more at insisting, at repeating itself enigmatically than at saturating, gratifying or suturing itself in some fashion.” This motif of repetition is ubiquitous in “In the End,” so much so that we might wonder, if desire is invariably the desire for the old, whether singing about desire’s incapacity for novelty can lead to something new.

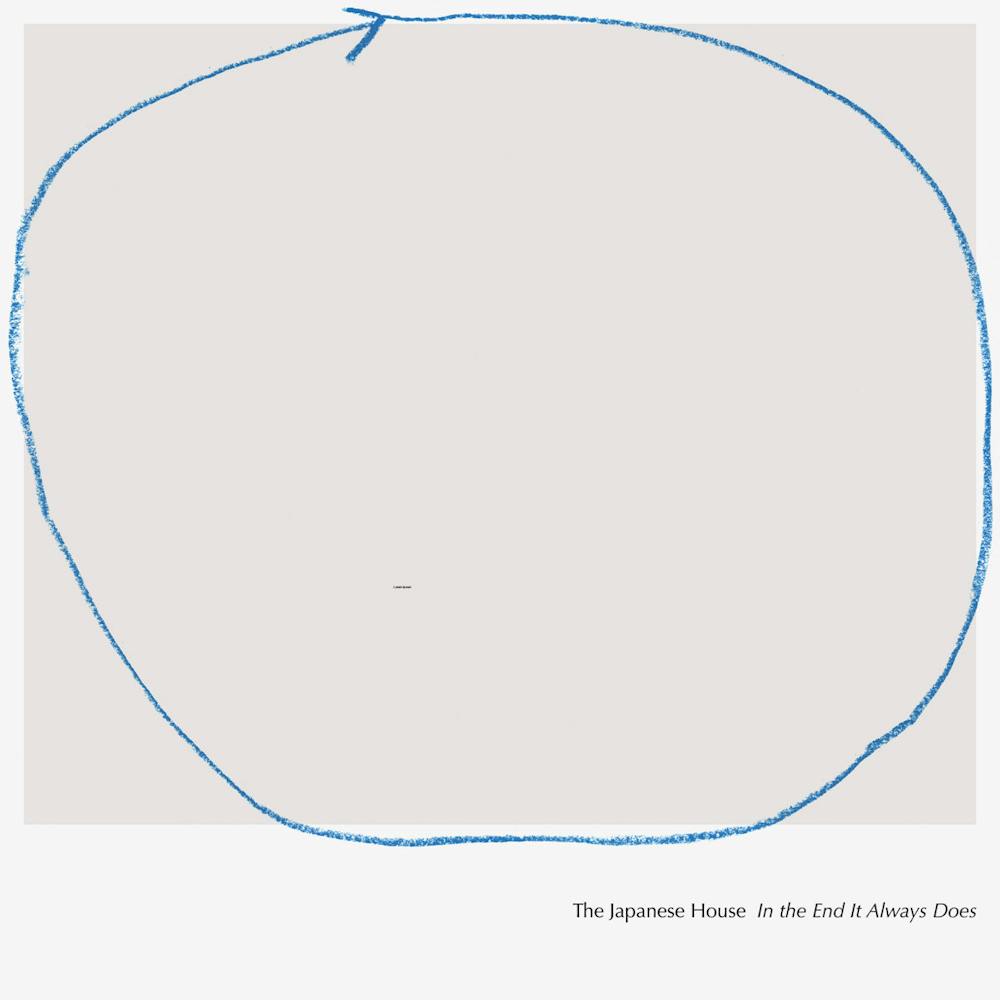

I want to end by dwelling briefly on the way in which the album cover, too, captures the idea of coming full circle. The mark of the blue crayon, like the movement of “In the End,” traces the vain detour taken by desire, only to circle around a void and begin anew on its old path. This detour, as “In the End” shows us, is one that never ceases to disturb, disorient and queer us. But Amber Bain’s music – even as it does not shy away from delivering emotional gut punches at certain moments – nevertheless manages to secure a mode of enjoyment proper to this shattering of the self.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.