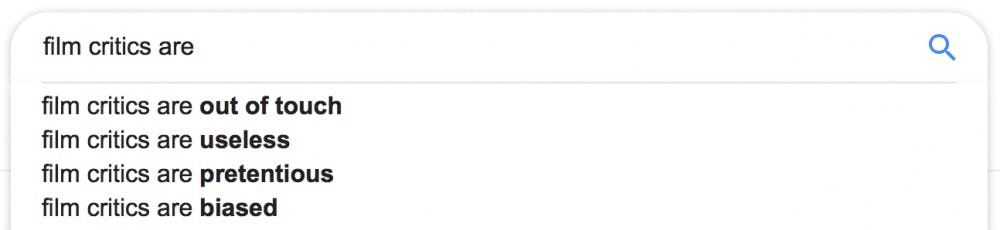

Much discussion has erupted in recent weeks regarding the (purportedly) fading necessity of reviews. In an age of discontinued Netflix-star-ratings, Amazon top customer reviewers and enraged YouTubers, the long-form reviews of movies, books or music that once dominated newspapers are increasingly seen as antiquated or downright ignorant. Ahead of the Oscars on Sunday, staff writer Joel Kohen, culture editor Will Atkinson and design editor Nina Wilder chimed in with their opinions as to why thorough media criticism still deserves a place at the table of today’s journalism.

Joel Kohen, staff writer:

I have a confession to make: I have never liked David Foster Wallace. His monumental, 1,079-page novel “Infinite Jest” struck me as an overly ambitious result of infantile narcissism; I found his popular essays (“This is Water,” “Tennis, Trigonometry, Tornadoes,” etc.) to be but a collection of pretentious platitudes by a self-absorbed philosophy-bro, and his carefully crafted literary persona is to me the impersonation of a pseudo-intellectual vulgar Marxist who should have abandoned his trademark bandana by the time he graduated college.

Sure, this isn’t the nicest thing to write. The tone may strike the contemporary reader as harsh, unfair or inappropriate; after all, Foster Wallace is among the most popular authors of the last three decades. Every once in a while, literary critics dare say that a certain book “had its moments, but failed to live up to the expectations” or that it “is empowering, yet lacking in a few literary aspects,” but the classic takedown-review, in which a much anticipated book is torn to shreds, seems to be a relic of the past.

When the New York Review of Books ran an article in 2013 by esteemed poet Frederick Seidel on Rachel Kushner’s bestseller “The Flamethrowers,” his scathing verdict wasn’t well received. After lambasting the popular novel for being disinterested in its language, characters or motorcycles, the NYRB’s West Coast rival Los Angeles Review of Books immediately published a response, calling Seidel “callous,” “a tad sexist,” “tone-deaf” and “cruel.” Only a few months later, renowned critic Lee Siegel took to the New Yorker to declare that he intended “never to write a negative book review again.” Finally, the millennial-favorite BuzzFeed Books decided to cease publishing critical reviews altogether in November 2013, adhering to a strict “no haters” policy.

The problem with such everything-goes, no-mean-words criticism is that it refuses to take literature seriously: It pretends that all books are created equal; that art is merely a pastime that deserves no honest discussion and ultimately, isn’t really worthy of our time. By praising masterpieces and emphatically rejecting what unrightfully purports to be grand art, literary critics may indeed sometimes display an inflated ego or provoke their readers, but the subsequent controversy is proof of a far larger truth that I believe is worth preserving at all costs — it shows that we care. On a campus obsessed with leadership positions, polished resumes and prestigious internships, a genuine dedication to art may be a somewhat lonely and often marginalized commitment, but blindly adapting such an attitude grants more legitimacy to the pre-professional musings of stressed-out tweens than they perhaps deserve.

The prohibition on unfavorable criticism relegates literature to the level of a negligible fad that has no bearing upon the legitimate interests of 21st-century youth. While students zealously debate whether a fraternity has risen to “top tier” or if a certain consulting firm promises a larger resume boost than another, books are thought to be inadequate subjects of discussion.

Why do so many see contrarian opinions on literature as dangerous rather than stimulating? Those eager to rid the culture industry of verbose comments often point to a damaging effect that these may have on aspiring artists — by having their work attacked, these artists are allegedly alienated from their more established peers. Yet I contend that a perfectly harmonic world in which all creative output is deemed equal would present an even bleaker vision. Not all authors write for the sake of writing; many of the greatest novelists and poets of all time sought to elicit a response from their audience, which they would no longer receive if book reviews were reduced to long-form synopses with a few compliments sprinkled in.

Judging takes time, for it requires the critic to go beyond the mere two weeks that one may spend on a novel. It demands precision, a knowledge both of literary and general history, as well as insights into psychology and cultural theory. And yes, critics make mistakes (lots of them, actually). Yet I remain convinced that, for example, William Faulkner is a superb author while David Foster Wallace simply is not — an opinion that some may find misguided. The right conclusion would be to see such a contradiction as an opportunity for an exchange of ideas, not as an attack on whoever holds a different opinion. That most Duke students would be hard pressed to name a single major, high-brow novel published in the last few years surely has multiple causes, but the nonexistence of grandiose, controversial reviews in their media is one of them. Absent notorious provocateurs like the early Norman Podhoretz, Gore Vidal or the herculean Dr. Samuel Johnson, it seems almost fitting that literature is all too often regarded as a tedious and antiquated interest.

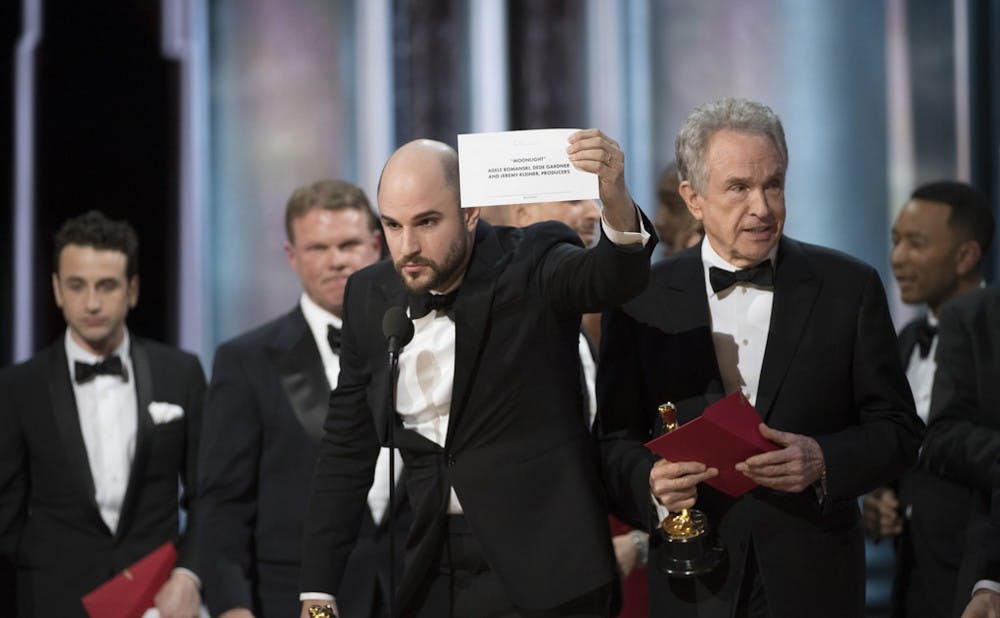

The copious attacks on the job of the critic, as they are sure to multiply in number ahead of the Academy Awards, thus miss the point: that some critics make dubious, sometimes outrageous, assertions is their mistake, but pretending that they have lost their purpose will not address that. As such, I am glad that the Chronicle still publishes outrage as often as elation. The virtuous antidote to bad criticism is more criticism, an honest, even polemical counterargument that challenges its object rather than forbid it. As such, I happily invite all those wishing to defend David Foster Wallace to make their case.

Will Atkinson, culture editor

I’m going to break the rules a bit here with my thoughts on criticism. Specifically, like most things on the internet, there’s far too much of it. This opinion may be a bit unbecoming of someone with the title of “culture editor” (aren’t I supposed to be the resident critic of this section?), but the instant-review mill that is cultural criticism today should make anyone justifiably skeptical of its efficacy. With the possible exception of literature, this race to publish reviews applies to all kinds of media, but I find it particularly prevalent in music.

Every year, it seems like the annual ritual of year-end lists happens earlier. (Next year, I expect I’ll have to submit my top 10 albums on Thanksgiving just to keep up.) Call it the Pitchfork-ization of music criticism: the obsession with rankings and lists; the need to quantify praise, literally, to the nearest decimal place; and — perhaps most crucially — the elevation of perceived cultural import over all else, sometimes at the expense of the music itself.

But this isn’t just Pitchfork’s problem. The sheer volume of content on the internet, and the rapid pace at which it arrives, means that there’s only so much that can be said about an album that hasn’t already been said by someone, somewhere. By the same token, the online review has taken on the same status that music has since the rise of streaming: instant, expendable and (often, when it comes to compensating its creator) dirt-cheap.

It’s been interesting to see the way outlets have adapted to these changes, with some dropping the facade of longform criticism altogether. Consequence of Sound, for example, has taken to publishing quick-hit blurbs (“The Good,” “The Bad,” “Essential Tracks” and the like) in place of reviews, a move that’s oddly refreshing amid the steady stream of 1000-word takes. The A.V. Club, meanwhile, tends to favor weekly roundups with the occasional full review, while Pitchfork has seemingly only doubled down on their list game, publishing the 50 Best Shoegaze Albums and following it up two years later with 30 Best Dream Pop Albums, for those who care about the difference. Presumably, lists get clicks, and a once-yearly tradition now occurs almost monthly.

The side effect of this race to deliver content is that music reviews increasingly seem to focus on the cult of the artist — the marketable, autobiographical narrative surrounding any given work. It’s no wonder: When you’re at one end of the PR chain for an album rollout and under pressure to publish within hours of release, it’s difficult to assess the work on its own merits, much less pen a thoughtful, personal reaction to it.

To see this trend in action, one need look no further than the end of last year, when Mitski’s “Be the Cowboy” dominated the year-end lists (rightfully, I’d add), taking the number-one spot for Pitchfork, Consequence of Sound and Vulture and placing in the top 10 in NPR, Stereogum and The New York Times, among others. This was an album that was really quite experimental in its treatment of pop music — 14 songs all around the two-minute mark, drawing from disco as much as country and vaudeville, full of skewed chord changes that defy easy resolution, all held up by incredibly dense and varied production — yet a great many recaps of the album seemed simply bent on decoding the “cowboy” mythology at the center of its title, whether as an allegory for Mitski’s empowerment as an Asian-American female artist, or for a subversion of toxic masculinity, for the rootlessness of a childhood spent moving constantly, or all of the above.

While these themes certainly speak to the whole of “Be the Cowboy,” they tell us relatively little about what actually makes the songs so special for the listener, and they minimize the real sense of craft put into the project by Mitski, who is without a doubt one of the most talented songwriters, on a purely technical level, working in the indie world today. When one considers that Mitski herself has said that most of her songs are odes to music, it’s all the more baffling that the music — what the album is all about, really — takes a back seat.

Of course, this isn’t to advocate for some sort of retrograde, music-isn’t-like-it-used-to-be formalism in music criticism, or to ignore the overarching emotional themes that charge an artist’s work. Rather, it’s to acknowledge that all good music — like good cinema and good literature — has a craft to it. And to pass over that craft in favor of the quickly digestible narrative surrounding it (a narrative that’s often formulated by the critics themselves) does a disservice to the artist.

It’s something that I’ve always felt like film criticism has prized. (Nina, correct me if I’m wrong.) Most good film reviews, in my experience, remark on acting, editing, cinematography — the craft of the film — in creating a more complete assessment of the totality of the film. For whatever reason, there doesn’t always seem to be an equivalent in music criticism, and music critics would do well to take some cues from their film counterparts.

Rarer still are the reviews that let a work settle over months or even years, capturing the subjective experience of the reviewer rather than attempting to be the end-all-be-all reaction of a first listen. When it comes to our work at Recess, we have the unique opportunity to let writers to do just that. A previous editor of this section once warned me against letting Recess “devolve into the Yelp! of cultural criticism,” and it’s a fate I’ve steadfastly (if not always successfully) tried to avoid, whether that means encouraging dual reviews à la The New Yorker or abstaining from a quantitative rating system.

And this, too, is why we have the “In Retrospect” column: It’s founded on the idea that criticism, like most writingjournalism, is really nothing without acknowledging the person behind the writing. Taking a look back at the albums or films or books that painted our most formative memories often does more justice to the work — and to the reader — than any 24-hour review would do. There may be a lot of criticism out there, but there’s still room for criticism that’s thoroughly attentive to craft, thoughtfully constructed and unapologetically personal.

Nina Wilder, design editor

Pauline Kael, a woman you’ve most likely never heard of, completely revolutionized film criticism in the 1960s. Well, it began in 1953, when she was overheard by the editor of City Lights magazine in a coffee shop, arguing with a friend about films. The editor asked her to write a review of Charlie Chaplin’s film “Limelight,” which she so-smartly called “Slimelight,” and her career in film criticism was born.

Kael hated the idea of objectivity. “I worked to loosen my style — to get away from the term-paper pomposity that we learn at college,” she once said. “I wanted the sentences to breathe, to have the sound of a human voice.”

For Kael, films were a personal experience, so criticism was, too. She wrote, I imagine, how she spoke: passionately and unapologetically. Most of her reviews hover around 10,000 words. She never bothered with the contemporary standard and formulaic approach of summarizing the film, outlining its merits, tongue-clucking its shortcomings and wrapping up with the non-committal, “neither-here-nor-there” declaration.

Kael believed art was the formalized expression of experience, and her job, consequently, was to evaluate a film’s success in conveying experience. Not a movie’s craft — a component of film criticism that Will appreciates, as do I — but its ability to address its audience. She was interested in the immediacy of movies, the emotions they provoke, or don’t; a film’s failure wasn’t necessarily in its subpar directing or flimsy writing, but its inability to connect to a broader human experience. She could care less that “2001: A Space Odyssey” reimagined the sci-fi genre or presented dazzling aesthetics. “It’s a monumentally unimaginative movie: Kubrick, with his $750,000 centrifuge, and in love with gigantic hardware and control panels, is the Belasco of science fiction,” Kael wrote. What does heart-stopping cinematography matter if its meaning can’t even be parsed out?

Most people — filmmakers, film critics, magazine readers in general — hated (and still hate) Pauline Kael. In a 1980 article titled “The Perils of Pauline,” the former New York Times book reviewer Renata Adler writes, “[Kael] hardly praises a movie any more, so much as she derides and inveighs against those who might disagree with her about it.” She was viewed as a deliberate contrarian, which, as Joel points out, automatically devalued her opinions. Most panned her writing as self-indulgent, overly critical and baseless; cinephiles take personal affront that she saw no value in films made by the likes of Stanley Kubrick, Federico Fellini, Ingmar Bergman and Terrence Malick. And, given her deeply personal approach to film criticism, her writing is often thought to be useless or widely unrelatable — who cares that Kael felt (or didn’t feel) deeply moved by a film? What about its technical merits, or the contexts in which it was made?

I’ve always found it difficult to teach film criticism to myself, to my writers, to whoever is looking to learn. Certainly, reading as many different pieces of criticism from as many critics possible is an excellent start. But what are the rules — or, what should they be? There are formalities of criticism that I find valuable: close readings of scenes, an interrogation of the film’s real-life contexts, examinations of the filmmaking techniques used. As Will stressed, part of the critic’s job is to evaluate a work of art’s technical execution, the ways it is able to work within the medium’s outlined parameters and challenge them, too.

Then again, if I wanted a formal analysis of Francis Ford Coppola’s use of parallel editing in “The Godfather,” I could probably search JSTOR and yield innumerable results. Criticism, I believe, should do what Pauline Kael always tried to do: tap into a style of writing far more intimate and experience-based. Films do not exist without an audience, nor should they. What the critic experiences when watching a movie matters, because the relationship between a film and its patron matters — and that relationship should be meaningful, emotional and intimate. A truly brilliant film deeply affects you, and it certainly never leaves you.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.