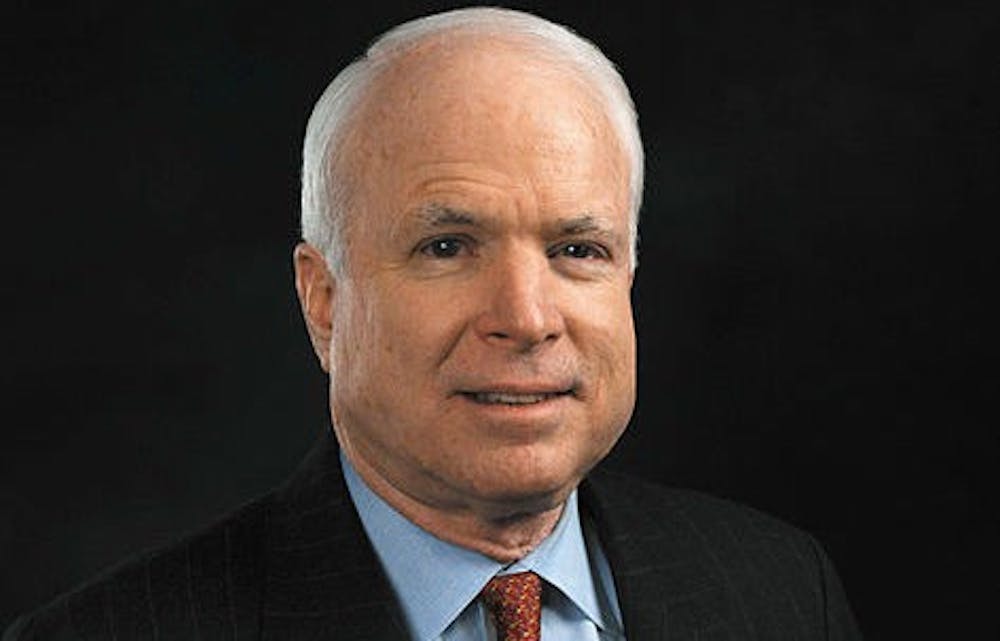

On the 25th of August, one American “[came] to the end of a long journey” to, as he put it, “[make] a small place for [himself] in the story of America and the history of [his] times.” That American was John McCain.

Six days later, another American—watching as the rest of America convened in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda to finish the last sentence of McCain’s chapter in the “story of America and the history of his times”—cried. This American was me.

Countless times this past summer, I guided constituents of West Virginia and North Carolina through the halls of the Capitol to this Rotunda, the most immaculate room in the Capitol whose lofty height compelled gasps of awe and pride that this was ours, as Americans. As I watched—from here at Duke—McCain’s stars-and-stripes-draped casket lie in the center of that exalted room, whose history and influence on pilgrimaging Americans I had come to know so well, I couldn’t help but weep because I recognized this feeling.

Mere weeks earlier, I had wept in that same great Rotunda. One evening, toward the end of my time interning for a member of the Senate, I heeded the advice of a beloved aide in the office and ventured once more through the underground tunnels to take in the full grandeur of the Capitol before leaving for the real world and for Duke. Without the hundreds of visiting schoolchildren and bustling staff filling its walls, it was hauntingly quiet. I had it to myself to take in and to attempt to grasp its full weight, to appreciate why it was there and I with it.

Eventually that evening, I made it, once more, to the Rotunda. I regarded, in new way, the statues of Washington and Jefferson and Lincoln and King and Reagan that I had passed and described so many times before, all floating upon the transcendent legacy of the American dream. And I sensed that they, too, were watching me, watching me grasp, heart and soul, towards that “more perfect” dream of what America could be. I felt, only for a second, to be small in the great halls of great American statesmen. But in that smallness, that necessary and weighted and igniting smallness, I understood a bit of what it meant to have political courage, to dare to dream the dream of America like John McCain had. And so I cried.

Crying for the loss of John McCain as he laid in state was similar to this moment, but in one way profoundly different: now, Washington’s and Jefferson’s and Lincoln’s and King’s and Reagan’s immortalized figures were joined by another exceptional shaper, dreamer, of America—McCain. No longer did I and the rest of America have him alongside us to toil on that mission to dreaming America into existence; rather, as McCain joined the ranks of those who concluded their long and illustrious chapters in the “story of America,” he made the legacy which we must uphold heavier to bear.

America is no more than a dream, a dream that inches asymptotically towards a reality only through the sacrifice, allegiance and noble struggle of the politically courageous: those like John McCain.

Political courage is not about blindly adhering to an individual, party or ideology, nor about standing self-righteous, unwavering and unable to compromise or engage with the other side. It’s not about being contrarian for the sake of causing division or proving a point, nor about being bombastic or controversial for the sake of shocking or provoking others. It’s not about “do[ing] battle with the left” or the right, nor about using blacklists or disparaging slander or rigged elections to attempt to keep some in line and to silence others.

Political courage is not about claiming victimhood or shielding oneself from the world with self-pity, fear and moral apathy, but is, in many ways, about making yourself vulnerable for the sake of strengthening yourself, advancing a cause and serving a higher purpose. It’s about doing what’s right when it’s hard; having a confidence and independence of mind when you know others will be quick to question and criticize you; pointing out the wrongs of that which you love because of your love; pursuing truth for the sake of truth—even when it falls short of your hopes; having the humility to bear your imperfections and admit to your own offenses and mistakes; being guided by the legacies you’ve inherited with humble servitude; and committing your whole and honest self to a pursuit greater than yourself. As many distinguished Americans have reminded us recently, John McCain—in all of his faults, which he was ever-willing to admit—did all of this.

I cried, and I cry, because I fear we don’t have enough exemplars of such virtues of political courage—not in Washington, D.C., not here at Duke.

As an American, I look to McCain because I, like him, yearn to serve this “big, boisterous, brawling, intemperate, restless, striving, daring, beautiful, bountiful, brave, good and magnificent country,” if only half as much as he did so faithfully, so enduringly, so selflessly.

As a conservative, I look to McCain because he proved that conservatism, at its core, is a nature and an outlook on the world “that hardly requires adherence to a particular set of policy positions.” He, among other icons of the American conservative movement like “Ronald Reagan, Abraham Lincoln [and] Alexander Hamilton,” never felt that he had to prove his conservatism to his peers and constituents, nor did he permit his conservative convictions or association to a political party to obscure his allegiance to his higher calling as an American that, as he remarked in his farewell letter to the world, “meant more to [him] than any other.”

Calling out his own party and its leaders from time to time, for McCain, came from the understanding that “some principles transcend politics. Some values transcend party,” and “he considered it part of his duty to uphold those principles and uphold those values.” Admittedly, for as long as I’ve self-identified as a conservative—especially since the 2016 presidential election and since arriving at Duke—I’ve been faced with numerous ethical dilemmas within political circles that have challenged my fundamental comprehension of what it means to be a sincere conservative and a committed American. My humble aspirations towards political courage—of the “romantic” McCain variety—have guided me during those testing times to confirm that I am a conservative before I am a Republican, and to put my country before my party.

As a Duke student, I look to McCain as I write this column out of a profound appreciation for what Duke is and a profound hope for what it can be, with the right measure of devotion, hard love, honesty and that same unwavering optimism with which I arrived at Duke.

So, I devote my column and my great vision for Duke, conservatism and America—my political courage—to you, John McCain.

Lizzie Bond is a Trinity sophomore. Her column runs on alternate Fridays.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.