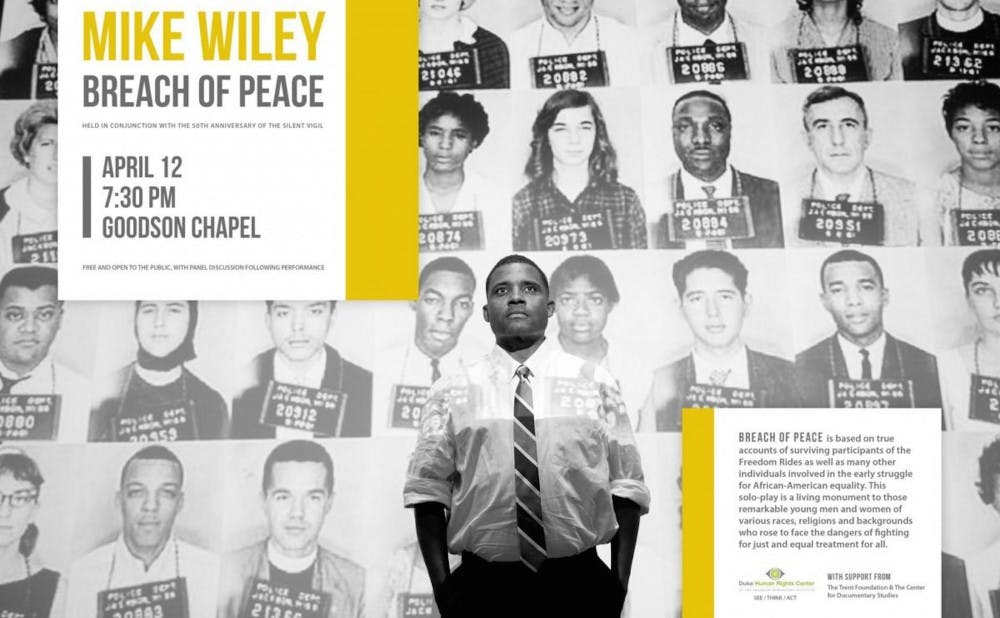

Watching Mike Wiley’s one-man play “Breach of Peace” was a bit of an otherworldly, other-era experience. The hour-long play, performed April 12 at Goodson Chapel, chronicles the history of the Freedom Riders, a group of civil rights activists who rode interstate buses in the 1960s South to call to national attention the non-enforcement of two Supreme Court rulings that mandated the desegregation of public bus systems.

Wiley’s performance was certainly an ode to this historical pathway. However, my bewilderment was magnified by the sensation that Wiley was opening up this time capsule but not revealing all its contents. The most impactful component of his play was not necessarily the performance itself but rather the video montages that bookended it: The first montage served to immerse the audience in the context of the Civil Rights movement through a diversity of carefully-selected clips that portrayed stoic marchers protesting, tenacious students conducting wade-ins on segregated beaches and people of faith fervently worshipping in their local churches.

In order to ensure that the audience’s absorption in this era would and could not be romanticized, Wiley refused to shy away from violence, including clips of white mobs harassing activists or beating them until blood streamed down their faces.

“We have to complicate history, we have to show that history is not clean," said Wiley. "It’s not sewn up with a button, it’s messy and complicated through and through."

The video montage screened at the end of his performance served to reel the audience out of history, allowing them to trace the historical continuity from the 1960s to now. Clips of the Freedom Riders stood alongside videos and photographs of current-day protesters and activists, allowing history to become tangible and feel all the more relevant: What the Freedom Riders accomplished sent shockwaves into the future, and we wouldn’t be where we are today if it were not for them.

If the montages managed to be elucidating and arresting, Wiley’s performance at times felt hermetic and difficult to grasp. The play itself served more as an ode to another era and did not draw any connections between the Freedom Riders movement and modern day. A quick perusal of the history of the Freedom Riders reveals a number of salient questions that remain pertinent: Is the division between the federal and local governments a barrier to increased civil rights? What are the implications when politicians equate the demonstrative actions of activists with the discriminatory behavior of those attempting to maintain the status quo?

The historical continuity of questions like these was not addressed in the play yet was consistently emphasized by Wiley in our interview. For example, he drew parallels between Bobby Kennedy’s request that the Riders “show restraint” and Trump’s comments regarding the white nationalist rally that took place last year in Charlottesville, Virginia.

“That’s why what Donald Trump said about the white nationalists as well as the peaceful protesters in Charlottesville is stuck in the craw of so many Americans of a certain age, because they remembered Bobby and John F. Kennedy equating these Freedom Riders and these racists to ‘extremists on both sides,'” Wiley said.

Wiley also drew strong corollaries between the Freedom Riders and the Parkland, Florida, students leading today’s gun reform movement.

“People get upset about the Parkland students, saying, ‘These kids are being used for a political agenda,’" Wiley said. "Well, if we go back to the Civil Rights movement, we see people saying, ‘Oh, Martin Luther King is just using these young people to get political traction.’ It’s just not new, it’s not new at all.”

Additionally, the play was somewhat disorienting due to the fact that Wiley played more than 12 different characters. Although he changed from one personage to another by changing his voice and posture and revealing a headshot of the character on the main projector, it was difficult to tell the different characters apart because they all utilized language in the same manner and shared the same linguistic style of speaking. The blending of narratives was further exacerbated by the sheer number of names and locations that Wiley listed.

However, these complications may not have bothered the Class of 1968 alumni, for whom the event was organized and who constituted a majority of the audience. These individuals came of age in the 1960s and likely require a less simplified contextualization than someone my age would. Additionally, the one-man play is targeted toward a general audience of high schoolers and middle schoolers and may avoid being too complex or divisive.

“At first I thought the play would be a supplement to what they were learning in schools, but I’m increasingly seeing that it’s now the whole package," Wiley said.

Anyone familiar with the Civil Rights era knows that the Freedom Riders left an indelible mark on American history. Even as Wiley accentuated the historical parallels in our conversation, his play managed to capture and transmit their story but not the imprint it left behind.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.