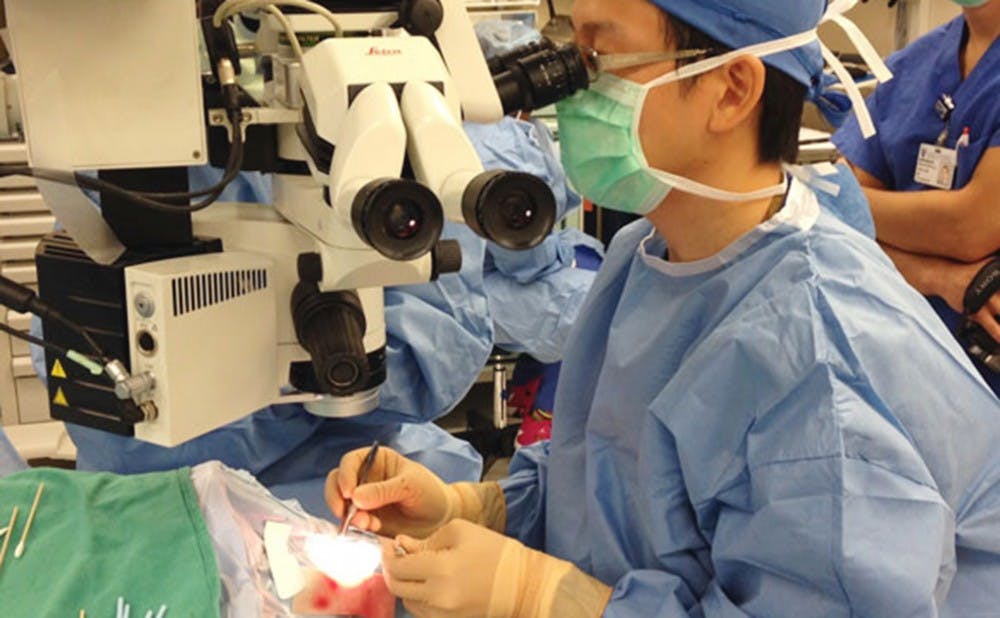

Dr. Paul Hahn, eye surgeon at the Duke Eye Center, fitted patient Larry Hester with the first bionic eye—known as Argus—in state history on Wednesday. The Chronicle's Shreya Ahuja interviewed Dr. Hahn for more insight into this groundbreaking surgery.

The Chronicle: What was the condition of Hester’s eyesight before the surgery?

Dr. Paul Hahn: Larry Hester has conditional retinitis pigmentosa, which is a genetic disease that causes damage to the retinas, essentially the soul of the eyes. It converts light into a signal that the brain and the person can understand. So, if the retina gets damaged, you can’t see. So, he’s 66 years old now, and when he was 33 or so, he started to progressively lose vision. He has lost vision for the last 30 years to the point where he is today, or was previously, which is what we call bare light perception. That means he can barely tell when the brightest of lights are on or off. So if I shined a bright light in his eye, he might be able to tell when it’s on or when its off, but not much more than that. So he can’t see anything moving; if you put up a couple of fingers in front of him, he can’t tell how many fingers. He certainly can’t read any of the letters on the [eye] chart.

TC: Can you explain the “bionic eye” technology?

PH: The technology has two parts; two physically separate parts. So the first part is a pair of glasses—a special pair of glasses that has a video camera right in the middle of it. That video camera is connected by a wire to a little computer that’s about the size of two or three decks of cards. And that little computer is something that the patient wears on their belt or puts in their pocketbook or on their shoulder or wherever they want. That computer processes that video camera, which sends it back up to the glasses and then the signal stops there. And that’s the external part of the device.

And then there’s the internal part of the device. Once that signal gets back up to the glasses, it communicates wirelessly to the part of the device that is surgically implanted. The part that is surgically implanted consists of basically an antenna—it’s called a coil—that goes around the eye to a little microchip that is surgically implanted on the surface of the retina. And what that microchip does is that it stimulates the part of the retina that is still not damaged by retinitis pigmentosa. Retinitis pigmentosa damages a certain part of the retina called the outer retina, and that’s just a part of the eye that is damaged in a lot of retinal diseases. But the inner part of the retina is often better preserved. This part of the chip stimulates the inner retina.

TC: What happens after the device has been turned on?

PH: I think the most important thing that I tell patients when they hear about this is that question. When a lot of people hear about this technology, they jump ahead to maybe what it will be in the next 100 years or 50 years or ten years or however many years. But the first thing I tell patients is that with the technology you’re not going to be able to drive. You’re not going to be able to read. You’re not even going to be able to recognize faces. What this technology does give you is flashes of light that sort of correspond to things that are going on around you. It’s a 60-pixel implant, of which 55 pixels are turned on. The amount of information you can get is a little bit crude, but when you compare it to not having any vision, it’s actually quite profound. So what these patients can do with this type of device is identify straight lines of a crosswalk or curb, which means they can kind of follow that path in order to walk straight. If someone walks in front of them, they can see that movement in front of them so they know to stop or move out of the way. Patients describe knowing where the windows are or where the doorways are so they can navigate the house better. They can identify things like their toothbrush or even their place settings.

TC: How long did this research take and when did the FDA approve it?

PH: This research has been going on for over 20 years. One of the special things is that the research originated at Duke. It was a resident at Duke who started doing this research while during his residency. He went on to Hopkins and then USC where he continued this research and then marketed it to a company called Second Sight, which has done a great job bringing it to the market. So, it was FDA-approved around February 2013. For the first year and a half, there have just been a lot of hurdles. For a while the device was FDA-approved but not yet available, meaning the company just had to manufacture them. So, for the first eight to ten months that was one of the issues. The other one of the big issues was insurance reimbursement. It’s a very expensive device; it’s estimated to be about $145,000. It’s expensive, but in context, these patients don’t have any other options. And if you think about things like a heart valve, they usually run around $150,000 also. Anyway, so insurance agreed to cover it and that’s been great. Medicare now covers this device, and Duke has been very proactive about doing this.

TC: Do you plan to continue performing this procedure?

PH: We do plan to continue doing this surgery. We’re not, however, quite full speed ahead. We want to see what the outcomes are for this device first so we can appropriately tailor further implants to the best of the patient needs.

TH: What do you imagine for the long-term possibilities of Argus?

PH: I think the implications for this device in general are twofold. From the individual patient perspective, I think this device offers a certain level of vision they didn’t have before. And for these profoundly blind patients, like I mentioned before, that type of improvement in vision is actually very significant. But one thing I’m very excited by is that, on a broader level, this device represents a new step forward into a new generation of patient care. So rather than previously, when patients lost vision, there was nothing we could really do about it. And for the first time, we can actually provide artificial vision. And this is the first approved generation of this device, but there will certainly be an Argus 2, Argus 3 and Argus 4 that will provide a better level of vision in the future.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.