He had no spouse, son or daughter, but when chemistry professor Jim Bonk died Friday, his family numbered some 30,000.

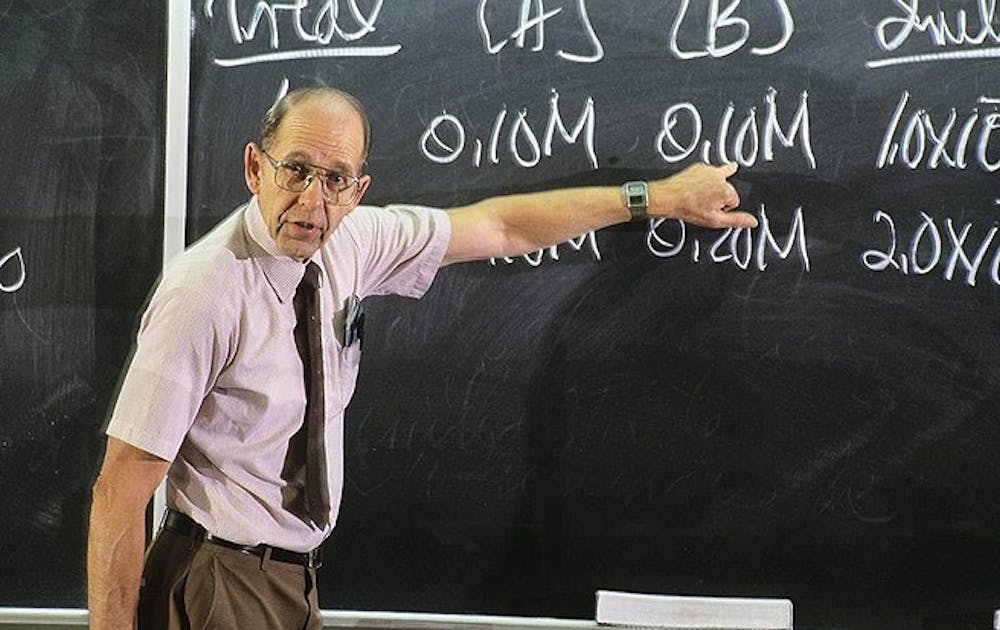

This is a low estimate for the number of undergraduates Bonk taught in his 53 years of service in Duke’s chemistry department. He taught the introductory chemistry classes, Chemistry 11 and 12, up until 2001, becoming so identified with the courses that students began calling them Bonkistry. He continued teaching through Fall 2012 even as he battled prostate cancer.

“He was the most student-centric faculty member I ever ran across. He was always concerned about the students,” said chemistry professor Steven Baldwin, who has worked with Bonk at Duke since 1970 and counts him among his best friends. “He would come in on a Sunday if a student was having trouble and just talk to them, whether it was for class or a boyfriend or girlfriend thing.”

Bonk’s colleagues remember him for his mentoring, humor and dedication to his students above all else. He excelled in preparing freshmen chemistry students and as director of undergraduate studies, said Baldwin, director of graduate studies in chemistry.

Bonk’s general chemistry course included two and sometimes three sections of 300 students per semester. He succeeded by making the material accessible to both the well prepared students and those new to the subject.

“He made the material accessible to everyone,” Baldwin said. “These are freshmen—some are hyper-prepared and some of them aren’t, and yet everybody had an opportunity to do well. He challenged the best and helped the people who needed help.”

Duke recognized Bonk’s teaching with many top honors, including, most recently, the University Medal for Distinguished Meritorious Service in 2011.

Central to Bonk’s teaching style was his sense of humor, which surfaced in several incidents that have since become campus legend. At one point, a group of students went out of town to party before one of Bonk’s exams. They asked to take the exam late, saying they were delayed by a flat tire on the trip back.

Bonk reportedly agreed, and at a later date administered the make-up exam with each student in a separate room. The exam was two pages long. On the first page was a straightforward five-point problem. The second page had just one question, worth 95 points: “Which tire?”

Reports varied about when exactly this took place, and just how much of it was true. Friends of Bonk said that he did not gloat about it, but quietly confirmed that something of that nature did occur.

At a different time, in the 1970s, students competed with each other by throwing pies at notable campus figures, acquiring points for each person hit. When a student came into one of Bonk’s lectures and threw a pie that hit him in the shoulder, the intruder had not anticipated the athleticism of his chosen target, who jogged several miles a day.

“Jim chased him all through campus including the trails on the golf course,” Baldwin said. “I don’t know who the kid was, but my understanding is he was a varsity athlete, so to be run down by a forty-year-old guy must have been surprising.”

His passion for chemistry manifested itself in teaching rather than research. Baldwin noted that Bonk rose to the rank of full professor without ever doing any research.

“It would be interesting to hear from the Duke administration if that would be possible today,” he said. “Chemistry education was what he wanted to do from the time he applied for this job until the very end.”

Bonk passed his passion for teaching on to others, like Lou Charkoudian, whom he mentored when she was earning her Ph.D. at Duke. She and a group of graduate students wanted more teaching instruction than they were getting, and they turned to Bonk for help. He worked with them to develop a class that introduced the basics of science through crime scene forensics.

Bonk cleared the administrative hurdles to allow the graduate students to teach the course, then sat in on their lectures and worked with them to revise and expand the course for the next year.

“He taught us to teach our passion, to not just spout out facts but teach them the scientific process,” she said.

Charkoudian will take up a teaching position at Haverford College this Fall.

When Bonk stopped teaching general chemistry, he started teaching an environmental chemistry course for non-majors. Last semester, he co-taught the Introduction to Chemical Research course with Christopher Roy, chemistry professor and assistant director of undergraduate studies. Bonk taught the first half and Roy taught the second. Bonk entered hospice care in December.

“Jim had always talked about how he was going to teach right up until the end,” Roy said. “He was pretty close. He was teaching up until last semester.”

Outside of the classroom, Bonk worked for the tennis team as an assistant coach and adviser.

He also brought with him tutoring skills that he developed as a graduate student at Ohio State University, where he tutored Coach Woody Hayes’s football team. Bonk developed a tutoring program for Duke athletes in the late 1960s, Baldwin said, which formed the basis for the “absolutely terrific” tutoring program at Duke today.

Bonk never married and has no surviving family members. Baldwin said that because of this, Bonk took on the responsibility of writing his own obituary.

“I was going to write him an obituary until one day he said, ‘Don’t worry about it, I’ve already done it,” Baldwin said. “He had this incredible sense of responsibility. He knew it had to be written, and there was no one else to write it.”

Bonk may not have family to carry on his name, but Bonkistry will continue to hold a place in the Duke lexicon.

“He has touched a lot of people, and his legacy will live long after he is gone,” Charkoudian said. “All the people he taught over the years that became researchers or teachers, there’s a little part of him in all of them. For someone without kids, he’s leaving quite a legacy.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.