The recent redistricting of North Carolina’s congressional and legislative districts has sparked conflict between those who believe the new boundaries are deliberately unfavorable to Democrats and black voters.

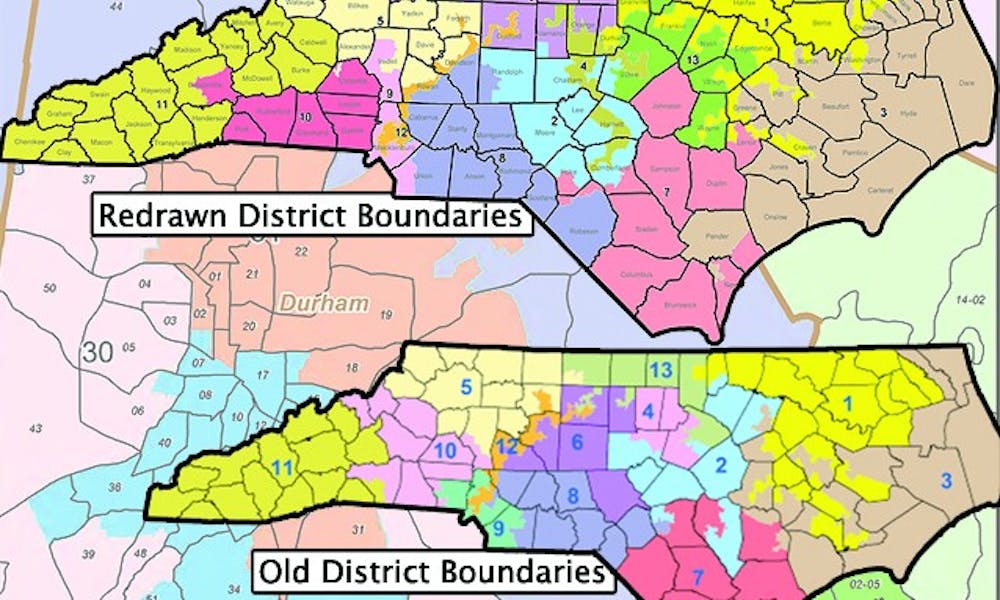

The North Carolina General Assembly passed legislation July 28 that redrew the boundaries of the state’s 13 congressional districts and districts for the state Senate and House of Representatives. This redistricting theoretically seeks to create equal populations in each district, but N.C. Democrats and civil rights groups are accusing the state and the Republican-controlled General Assembly of gerrymandering—redrawing districts for partisan gains. Democratic officials and some voters filed a lawsuit against the state Nov. 3 and a second lawsuit was filed Nov. 4.

“There are no ethics in redistricting, it is a straight power game,” said Ran Coble, executive director of the North Carolina Center for Public Policy Research. “Whoever is in power draws district lines to benefit their party.”

Redistricting is done every 10 years, and this year it follows the completion of the 2010 census.

Before the legislation was passed, there were seven congressional districts that were historically Democratic and six districts were historically Republican, said state Sen. Floyd McKissick, D-Durham. If the legislation remains unopposed through May 2012 elections, there will be three districts likely to vote Democrat in federal elections and 10 likely Republican districts, he added.

“The Republican majority has gerrymandered the state in order to reduce the number of Democrats who can be elected to Congress,” McKissick said. “That’s not exactly what I consider to be fair, reasonable or balanced.”

Lawsuits claim ‘packing’

The first lawsuit was filed by elected Democratic officials in Wake County Superior Court Nov. 3. A second suit was filed by four civil rights groups and 27 registered voters in Wake County Superior Court Nov. 4. Both suits aims to overturn the redistricting legislation.

The lawsuits claim the legislation involves “packing”—the practice of creating districts where minority voters are the majority population. In some districts, black voters were concentrated into districts that were already heavily Democratic due to the historical tendency for black people to vote for Democratic candidates, thereby decreasing their voting strength throughout the state, McKissick said.

Such methods of division violate the federal Voting Rights Act and the equal protection clause protected under 14th Amendment, Coble said, adding that the lawsuit will likely not be decided before the elections in May.

State Rep. David Lewis, R-Harnett, said Democrats are misusing the Voting Rights Act in order to garner Democratic votes.

“This is absolutely not a racially charged redistricting process,” Lewis said. “It is one in which we grant roughly proportional representation.”

The lawsuit also claims the redistricting legislation violates provisions in the state constitution requiring that district lines are drawn in such a way that they avoid splitting existing counties, districts and precincts when possible. The July redistricting plan splits 500 voting precincts, whereas the last redistricting plan in 2001 split only 149. According to the lawsuit, this could affect about 2 million adults.

Voters’ interests at stake

Anita Earls, attorney and executive director of the Southern Coalition for Social Justice, said this redistricting might cause confusion for voters, who may not know which districts they live in or which candidates to consider.

“[Under the redistricting] there is a street in Durham that is divided into four districts,” she said. “This means that your neighbor may have a sign in his, her yard for a candidate, but you may not be voting for that candidate.”

Duke will also be affected by the redistricting legislation on the state level, said Chris Ketchie, policy analyst and community organizer for the Southern Coalition for Social Justice. Students living on East and West campuses will now be in the same district, whereas under the previous division the campuses were in different districts. The areas surrounding Duke, however, are less uniform, Ketchie added.

Duke’s interests might also be at stake because its current congressional representative, Rep. David Price, D-N.C., will, as a result of the redistricting, now run against another Democrat, Rep. Brad Miller, D-N.C., said Pope McCorkle, visiting lecturer in public policy studies.

“David Price was in tune with the needs of Duke and knew Duke,” McCorkle said. “Duke loses in this process, to the extent that they may lose Price.”

Demography to ‘defeat’ redistricting

Bob Hall, director of Democracy North Carolina, criticized the redistricting for decreasing competitiveness in some districts, affecting voter turnout. If a district, for example, is heavily partisan, people might not be inclined to vote because they believe their vote will not affect the outcome.

But Lewis said he thinks the new redistricting will make the elections more competitive than years past.

“We sought to make this very competitive, and I think what we’ll have now is a much more balanced and competitive situation,” he said. “This will make the people much better served by their government.”

Although it is difficult to predict voter turnout, it is likely that the redistricting will not have a direct effect, Coble said, adding that even bad weather can influence voting behavior.

“Most voters think that redistricting is a very political issue so they turn their heads,” Coble said. “Instead voter turnout will depend on other factors such as how much candidates campaign here.”

If the courts do not overturn this redistricting, time will eventually nullify whatever errors were made in the process, McCorkle said.

“Demography will ultimately defeat the gerrymandering,” he said. “The demography of North Carolina is changing enough and becoming more diverse and multicultural, that in 10 years or so, even these maps won’t work.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.