Editor’s note: This is the first portion of a two-part series looking into drinking at Duke. Today’s focus is on the increase in alcohol-related incidents on campus and the University's education-based policies. Thursday, The Chronicle looks into the differences between Duke's alcohol policies and other schools' and whether Duke's is likely to change in the near future.

When Tom Szigethy came to Duke in 2008, alcohol seemed to dominate the social scene. Two years later, some measures suggest that little has changed—and the situation may have gotten worse.

University and police statistics show that alcohol-related incidents have increased over the past several years. But Szigethy, associate dean and director of the Duke Student Wellness Center, said Duke has increased discussions and education regarding the risks of drinking, which should eventually reduce alcohol’s detrimental effects on campus.

“I am always hesitant when people judge success based on the number of 911 calls made,” he said. “When I got here, you were not seeing as many students and professionals coming together. Now, everyone is starting to talk about the issue openly.”

Alcohol-related calls to services have increased this academic year—to 45 from 37 as of Oct. 1, said Duke University Police Chief John Dailey.

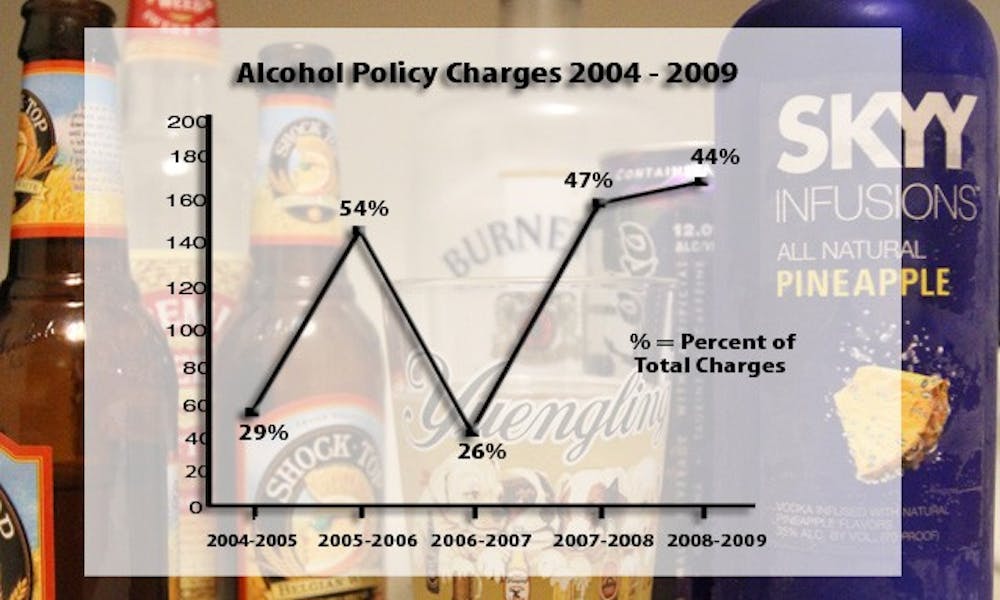

Alcohol policy violations have also experienced fluctuating growth since 2003. According to statistics from the Office of Student Conduct, there were 390 alcohol policy violations in 2008-2009, 173 of which warranted formal disciplinary action against individual students. There were 159 such incidents in the 2007-2008 academic year and 47 in 2006-2007.

“A cultural shift”

Dean of Students Sue Wasiolek, who has worked at the University for the past 37 years, said the number of student drinkers has been fairly consistent over the years but the intensity of drinking has increased. As a result, in recent years Duke has experienced more assaults, injuries, noise and property damage, she said.

Approximately 68 percent of Duke students reported drinking alcohol in the past 30 days, according to the 2009 National College Health Assessment survey. Nearly 40 percent of Duke student drinkers consumed five or more drinks in a row, at least once in the past two weeks. Binge drinking is defined as consuming five or more drinks in one sitting for men, and four or more for women.

Duke students seem to drink and binge at about the same rates as college students nationwide. According to the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 63.9 percent of college students classified themselves as current drinkers—43.5 percent were classified as binge drinkers.

Duke has not changed its alcohol policy substantially in the past two years and is not planning any major policy changes in the near future, Vice President for Student Affairs Larry Moneta said.

Moneta and Szigethy said they do not think changes to University policy will significantly alter student drinking behavior.

“It’s the cultural shift we are after—making it socially unacceptable or uninviting to get belligerently drunk,” Szigethy said. “And I don’t think we can get a cultural shift solely through policy.”

Rather than “laying down the law,” Szigethy said Duke combats alcohol-related issues using a “harm-reduction” model, which prioritizes reducing injuries and harmful behavior over strictly enforcing alcohol policies. The model relies on educating students to regulate their own drinking behavior.

“We have a whole population who are coming to Duke, yet they are blacking out and killing the brain cells that they are trying to educate,” Szigethy said. “I firmly believe that if the entire student population understood all the risks that come with drinking, any rational person would not [get drunk].”

Beyond the numbers

Szigethy said the success of his goals—education about the risks of drinking and increased collaboration between students and administrators—may not always be captured in statistics such as EMS calls and alcohol violations.

He added that the spike in EMS calls may indicate that students are recognizing the signs of alcohol poisoning and seeking help. More surveys and focus group studies are needed to assess the reasons behind the increased number of EMS calls and alcohol violations, he said. The Duke Student Wellness Center has not conducted such assessments because of limited staffing and frequent “crisis type” incidents.

Szigethy said he has raised awareness about the effects of alcohol and emphasized moderation in student drinking over the past two years. He cited the party monitor system as an example of efforts to curb dangerous behavior. Party monitors are now required to participate in an hour of face-to-face training. Previously, party monitor training was conducted online.

One of the only changes to Duke’s alcohol policy in recent years has been a six beers per person limit at BYOB events, Szigethy said. Recent Tailgate and Last Day of Classes reforms have also limited the quantity of alcohol students could carry.

At the 2010 LDOC celebration, when alcohol limits were in place, 19 alcohol-related EMS calls were made, down from 29 in 2009, Dailey said. Thus far, three alcohol-related EMS calls have been made during Tailgates and one student has been transported to the hospital, compared with two calls and one transport during the same period in 2009.

Policy versus practice

Szigethy said the alcohol policy itself is sound, but is typically enforced only when students exhibit disorderly behavior.

“In essence, we do wait until the person is much more intoxicated and can’t manage their behavior and is disrupting the community because of it,” Szigethy said. “Overall, the policy is working now. The question is, how do we enforce it?”

Duke’s policy prohibits students under age 21 from consuming alcohol, as mandated by North Carolina state law. East Campus is a “dry campus,” though of-age upperclassmen are allowed to keep alcohol in their rooms. However, Duke also offers an amnesty program which bars disciplinary action against students who seek medical attention after drinking too much.

Duke’s philosophy maintains that alcohol policy enforcement should be educationally focused rather than punishment-based, Szigethy said. Still, he finds merit in the “strict enforcement” model used by some other institutions that rigorously enforce alcohol policies on campus.

“Right now, we use a prevention strategy, and maybe we need to switch that priority,” he said. “I do think there are many professionals on campus who will be willing to go that route [of stricter enforcement].”

But given Duke’s emphasis on student self-regulation, a sudden switch to stricter enforcement of alcohol policies is unlikely.

“We all have a choice whether we are going to drink or not,” Wasiolek said. “We know the law; we know what we are supposed to do, yet we know some people will choose to [drink] anyway.”

“It’s a little counterintuitive”

In formulating its approach to student drinking, the University must focus on addressing the needs of non-drinkers as well, Wasiolek said. She added that students who consume little or no alcohol suffer from the effects of others’ heavy drinking, including vomit in the hallways and noise late at night. Last Spring’s NCHA Survey reported that nearly one-third of Duke students abstained from drinking in the past 30 days.

Bob Saltz, a senior research scientists at the Prevention Research Center who has studied college drinking said alcohol policies need to focus on all students, not just heavy drinkers. He added that light and moderate drinkers suffer more injuries and assaults.

“[Universities] need more universal approaches,” he said. “It’s a little counterintuitive.”

Injuries, assaults and other alcohol-related incidents, even if on the rise, may not cause changes in University policy.

Szigethy said universities sometimes wait until they experience a crisis situation before making significant changes. He pointed out that Duke changed its alcohol policies after Raheem Bath, 20, died from pneumonia after drinking too much in 1999.

“[Last year, Duke had] almost 20 students who came that close to dying because of alcohol, and we kind of blow it off because those students don’t die,” he said.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.