As another simmering summer day ends on North Carolina State’s campus, commotion broils around the Witherspoon Student center. A line of students—some swinging lanyards around their fingers, others high-fiving and reenacting stories from the night before—stroll past dozens of reporters and a gauntlet of anti-rape protesters to join the line for the evening’s entertainment: Tucker Max, the self-proclaimed womanizer and asshole and Duke Law graduate, and a screening of his new film I Hope They Serve Beer in Hell. The protesters silently pass out flyers, smiling as they let their posters speak for themselves: Stop Supporting Rape Culture, Real Men Respect Women and This Is Not Entertainment.

Inside the theater, the rape protester gathering is swapped for a gauntlet of post-college 20-year-old promoters, who all possess seasoned fraternity swagger. The welcoming party’s first gift is a red, IHTSBIH wristband, which further blurs the lines between movie premiere and frat party. Next is a black gym bag, stuffed with a bumper sticker, movie poster, T-shirt and beer mug. Compiled by Max’s company, Rudius Media, self-promotion has never been more shameless.

Now fully equipped for a gym-cum-room decorating-cum-Shooters progressive, attendees stroll past a wall of YOUR FACE HERE posters into the theater. Rap music (Project Pat, Young Jeezy, Geto Boys) bumps underneath the booming voice of executive producer Nils Parker, Max’s bulldog-looking sidekick who is the night’s emcee. “Hey there, bunch of tight-shirted guidos,” he barks at a group who enters. Then, turning to the crowd: “They walk around hearing trance music all day.”

Max stands off to the side at first, sipping from a red Solo cup, scrolling through his iPod, but eventually he jumps on stage. “Cocksicle?” he jokes as a few girls enter with popsicles in hand. The fraternity-meeting-style running commentary continues, but Parker and Max’s banter spares no one, as they are as likely to deride each other as they are the audience. “Don’t worry, I’ll stop speaking soon,” Parker says.

The protest, both in its subject matter and the individuals involved, features prominently in the duo’s exchange. “[The people outside] can’t accept reality, can’t make an informed decision. You got your rape whistle? You going to sit on it during the show?” Parker quips. “Fucking bullshit,” Max chimes in. “It’s not 1959 anymore.”

Bored with coming up with their own material, the pair then opens up the floor to the audience to tell embarrassing or humorous personal stories. This move benefits both parties: It provides fanboys the opportunity to out-Tucker Max the real Tucker Max, and subsequently offers Max and Parker pitifully easy targets to continue the derisiveness.

Bro No. 1 offers up a story about (surprisingly enough) attending a Duke Tailgate, getting “waste-facested,” drawing a swastika on a student’s door and breaking one of the televisions at the McDonald’s. “You sound like a fucking prick,” Max immediately fires back, crushing said bro’s hopes of gaining any sort of recognition for his outlandishness.

Other than this instance, every time Max’s law school alma mater enters the conversation, it receives a harshly negative evaluation. Perhaps Max is playing to his strengths with the N.C. State crowd, but his negative portrayal of Duke is painfully hypocritical. He takes every chance he gets to name-drop the institution, but nonetheless relates how terrible a time he had here. His relationship with Duke is a prime example of how Max paints himself as a tragic intellectual held back by unavoidable douchebaggery. Oh, that it should come to this, Tucker!

As Max quickly outdoes his adoring audience members’ stories with his most recent sexcapade at the goal line of University of Florida’s football field, one wonders whether to believe in the Tucker Max behind the self-promotion. He relates later on that this womanizing is a phase—that he wants to settle down, get married and have children.

But Max digs a new hole for himself with each morning-after blog post, photo upload and lawsuit. Furthermore, his self-aggrandizement must affect the organic nature of every new antic he embarks upon, prompting women to sleep with him for their own promotion, for the glory of the story. He clearly reaps the benefits now, but perhaps a more disquieting fate awaits Max, like that of the Frank Sinatra doppelganger Johnny Fontane in Mario Puzo’s The Godfather: alone, hosting women who don’t care or come back and watching his talent fade fast.

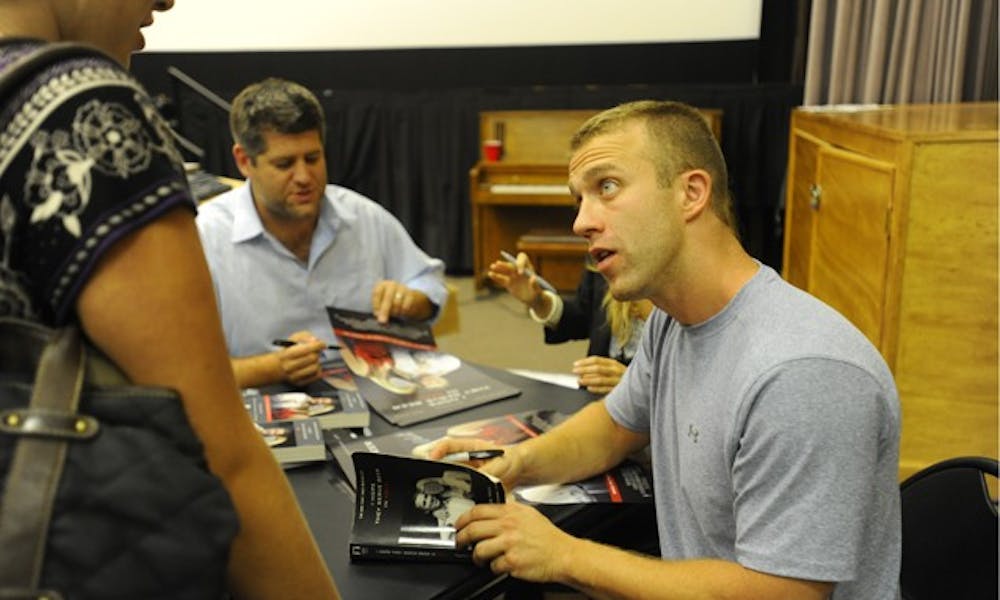

In the meantime, Max can enjoy the comical and bizarre effect he’s had on America’s youth. During the post-screening Q&A, a 20 year old stands up and invites Tucker to his home in Alaska to go fishing with him. A girl professes her love for Max and asks a question about his sex Rolodex (city name first, girl’s name second, special talent third). Another girl relates that she brought Max’s book to college instead of the Bible.

This intense, evidently religious following must hold a frightening mirror up to American culture. Max’s popularity undoubtedly reveals that society secretly savors salaciousness and is fueled by gossip. But it’s a commentary we hear everywhere and we see executed by similarly morally questionable, but far more complex characters—Mad Men’s Don Draper, for instance. But Max and his pseudo-fictional film counterpart lack depth and personality, and inspire no desire for further investigation. One can only hope Max exits his current life stage, negating the need for his place in American culture, and is flushed out of sight like another Internet phenomenon, JuicyCampus.

For now, as long as America continues to buy into the exploitation, Max can—and will—throw back his head, cackle and flash his devilish grin.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.