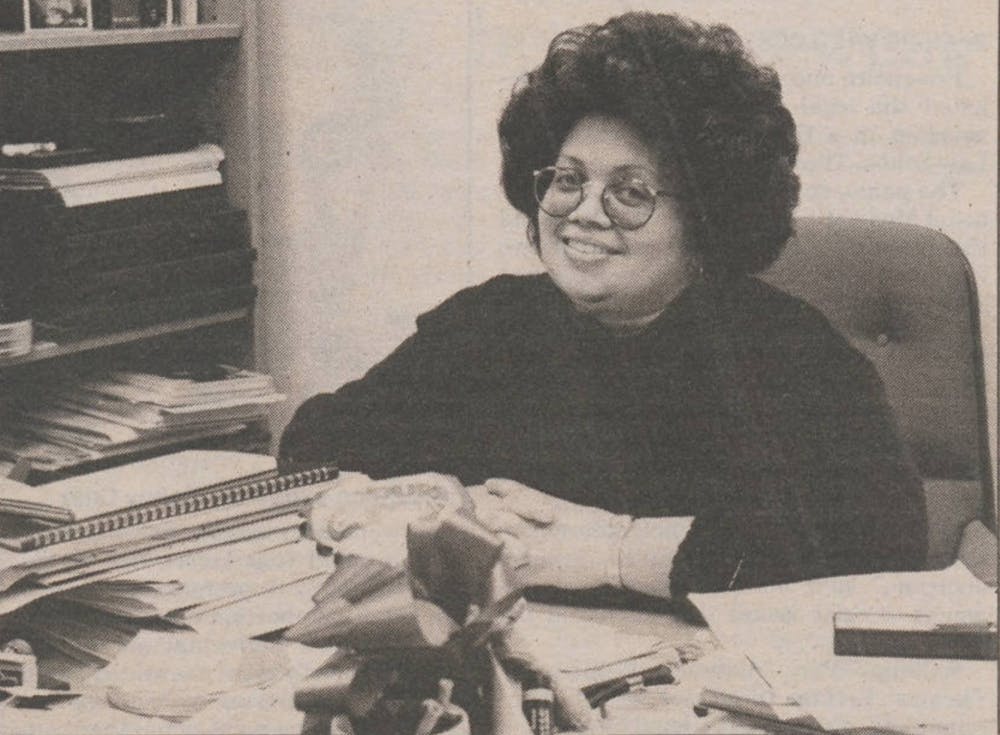

In Brenda Armstrong’s 69 years, the woman was a force to be reckoned with—and she was a force who made an indelible mark on Duke through her activism and care.

Armstrong, who died Sunday, grew up in Rocky Mount, N.C., before coming to Duke in the late 1960s, where she had no sooner arrived on campus than she began to change it.

Armstrong, Woman’s College ‘70, was a leader in the Allen Building Takeover in 1969, and she went on to become the second black woman in the United States to earn board certification as a pediatric cardiologist. As associate dean of admissions, she would mold Duke’s School of Medicine into a more diverse place.

“Dr. Armstrong represented the best of Duke’s ambitions and potential,” wrote Karla Holloway, James B. Duke professor emerita of English, in an email. “She was a fierce advocate for students, a clarifying voice for issues that directed Duke’s efforts in diversity and representation and how excellence accompanied these goals, and she represented how being an activist voice for change—from within the institution’s most challenging administrative structures—would make a critical difference in achieving a better Duke.”

From her undergraduate days as an leader in the Takeover to transforming the Medical School’s admissions process to make it a more diverse community, Armstrong’s legacy at Duke lies not only in the barriers she broke but in the ladders she built for others to climb.

The activist

Armstrong attended segregated Booker T. Washington Senior High School in Rocky Mount. When she arrived at Duke, black undergraduates had only been at Duke for a handful of years. It was not long before she became part of a growing movement to push back against racism on campus.

In an essay Armstrong wrote decades after her undergraduate years explaining her role in the Allen Building Takeover, she said that the Afro-American Society formed in 1968 as a result of “the living, breathing scourge on our attempts to get an education from Duke.” Armstrong would be chairperson of it. There were maybe 90 African Americans at Duke then, and some were the “onlies” in their dorms.

“Some of us came back to our dorm rooms to find Confederate flags on the doors with ‘n***** go home’ written over it,” she wrote in the essay. “Most of us never heard a friendly voice, except that of the dorm ‘maids.”’

After Black Week—an annual event organized by the Afro-American Society that brought speakers to campus and fostered discussion—in Spring 1968, black students gathered together and came up with 13 demands for the University. They met with administrators to discuss the demands.

Armstrong recounted finding out that Martin Luther King Jr., had been killed, and walking out of a French class the next day in tears to find other black students doing the same. They then peacefully occupied the president’s house to find out what Duke intended to do in response.

“We decided that we would demonstrate to the university our resolve,” Armstrong wrote. “We would demonstrate to the university that its racist ethos (and the pursuit of that ethos) was choking the academic, social and cultural life of some of the most gifted African Americans. We would not go down without a fight. Allen Building was on.”

In preparation, some students memorized the floor plans of the building as others made plans to bypass Duke’s communication with the media to directly project their message.

They planned to secure the building in three minutes or less, and they would not take any weapons. The students would only notify their parents once they were safely locked inside.

“None of us slept that night. Sixty or sixty-one students showed up at 6:00 a.m. for that fateful trip in a dark U-Haul truck down Campus Drive to the Allen Building," Armstrong wrote. "I cried, trembled and prayed as I rode in the dark. When the doors opened, we ran into the building and secured it as planned."

After the occupation ended, administrators tapped 13 students as the ringleaders and tried to put them on trial, but all the others surrendered as well.

“Most of [our parents] embraced us and supported us,” she wrote. “And all of them knew that their children had met their destinies without flinching, and had been ever defiant and undaunted. In choosing to confront Duke, we students had carved a place in history for ourselves.”

Holloway noted that part of Armstrong’s legacy and lesson for students is that the personal is political, and that there are direct means of having a voice that matters.

“Having a seat at the table is as much a responsibility as it is an opportunity,” Holloway wrote. “She handled both with grace.”

If the Takeover was a defining moment of her undergraduate time at Duke, it was only the beginning of her dedication to shaping the school into a more equitable place.

"The Allen Building showed us that there was nothing we couldn't do," Armstrong told The Chronicle in 2009. "What it did was validate what our parents sent us to Duke to do. They sent us here to be the next generation of leaders. In many regards, we owed the Allen Building to them."

The physician

Armstrong graduated from Duke’s Woman’s College in 1970 and completed a fellowship in Duke's School of Medicine that ended in 1979. She became just the second African-American woman in the country to earn board certification as a pediatric cardiologist.

As a physician, Armstrong was kind and caring.

“She had a real knack for being true with families and knowing how to communicate with them,” said Ross McKinney, chief scientific officer at the Association of American Medical Colleges and a former colleague of Armstrong's in the pediatric intensive care unit at Duke.

She was an equally good colleague.

“If I had to call her at night, no problem,” McKinney said. “She was as good as you can hope for—a truly committed, caring colleague.”

Armstrong would go on to spend more than 20 years as the associate dean for admissions at Duke’s School of Medicine, where she had a profound impact on the admissions process and the diversity of its classes.

Armstrong had a two-pronged approach to increasing opportunities for diverse candidates, said Mary Klotman, dean of Duke Medical School. Instead of just evaluating an applicant’s test scores, the school began to take a more holistic view of prospective students, considering their diversity as part of the equation.

“She changed the way we look at applicants,” Klotman said. “She actively went out and developed relationships and partnerships with undergraduate institutions—some of those were traditionally black colleges and universities—and actively recruited the very best.”

The change in the diversity of Duke’s classes began to reflect this effort in the 1990s and early 2000s.

“I was really in awe of how much she changed the profile of the Medical School’s student body,” Klotman said. “It was kind of a national buzz.”

Holloway, who was on the executive committee of the Academic Council at the time, remembered noticing a shift in the school’s academic quality and diversity.

“It was as clear an indication as Duke would ever want that pushing ourselves to create a more inclusive campus would also elevate our academic standing,” Holloway wrote. “She knew that would be the metric. And she delivered.”

'She cared a lot about the University'

The mark Armstrong leaves behind is as big as the intense effort and care that she poured into Duke for five decades.

“She cared a lot about the University,” President Emeritus Nannerl Keohane said. “She was an undergraduate, a professor and a dean. Both as an administrator and as a faculty member—and I gather from the records, as a student as well—she pushed really hard to make Duke a better place. She cared about the institution and she wanted to make Duke live up to some of its high ideals.”

Keohane said she best knew Armstrong for her voice in large staff meetings, in which she would stand up and advocate for increased respect and inclusion for staff across levels of the University.

As president, it pushed Keohane to be more cognizant of staff’s commitment to the University and desire to feel like part of its common goal.

“It meant that it was somebody I had to listen to,” Keohane said. “Sometimes it wasn’t easy because she pushed hard. But she pushed thoughtfully and what she said needed to be heard. I think it’s important for a university president to have people who are taking stands and pushing back, even if it’s not always easy.”

Keohane said that one of Armstrong’s significant influences was in her role as a conduit between Duke and Durham. Because she was respected on both sides, when Armstrong spoke for Duke or to Duke, people listened.

Aside from her work at Duke, she led a community track team called the Durham Striders.

In the broader community, she is being remembered as well. At the Durham County Commissioners meeting Monday night, Commissioner James Hill called Armstrong a “tremendous force here in Durham and at Duke.” U.S. Rep. G.K. Butterfield (D-N.C.) took to Twitter to share a memory of his longtime friend.

“She was fierce. What you have to know about Brenda is that she was incredibly caring, incredibly dedicated and she had no problem telling her truth to power,” McKinney said. “As a result, she really made a difference.”

Memorial services for Armstrong have yet to be announced, but Duke lowered its flags for the physician.

“She was remarkable in her courage, her joy and her example,” Holloway wrote. “I feel we have lost a part of our institutional spirit.”

Although Armstrong died four months short of the Takeover’s 50th anniversary, the physician and activist knew well the mark those early change-makers left behind.

“Our enduring legacy would be one of leadership, commitment, extraordinary academic and professional productivity. Indeed, such achievement through struggle and the ensuing myths created would be the stuff of legends,” she wrote in her essay about the Takeover. “And, on our shoulders would stand generations of black students to complete their unfinished business at Duke.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Bre is a senior political science major from South Carolina, and she is the current video editor, special projects editor and recruitment chair for The Chronicle. She is also an associate photography editor and an investigations editor. Previously, she was the editor-in-chief and local and national news department head.

Twitter: @brebradham

Email: breanna.bradham@duke.edu