In a race where its opponents have a head start of a few hundred years and several billion dollars, Duke has pushed the boundaries of education in an effort to catch up.

For the University, one way to keep pace has been pushing the frontiers of a new academic arena: interdisciplinarity. This word is both a direction and a brand, a strategy and a tactic, a vision and a sales pitch. In the fight for tuition money, brand-name faculty and research grants, the University has advanced by promoting itself as a place where traditional boundaries are crossed and new types of collaboration are explored. Duke’s focus on interdisciplinarity has yielded real gains, in terms of both reputation and research. But this move away from a traditional academic structure is also changing the University in ways that may have lasting impacts on students, faculty, and the institution as a whole.

Interdisciplinarity and Duke: a history

Though interdisciplinarity has received increased attention in recent years, it is not new at Duke. In 1988, under President Keith Brodie, a Duke self-study committee released a report titled “Crossing Boundaries: Interdisciplinary Planning for the Nineties.” The report contained hundreds of pages analyzing Duke’s fledgling interdisciplinary efforts.

Even two decades ago, there were “over 100 formal, interdisciplinary units, including Programs, Centers, Sections, and Institutes,” according to the report.

The report also sketched out a path for the growth of interdisciplinary programs at Duke, observing that successful interdisciplinary programs often grow out of a combination of core faculty interest and administrative support.

"That committee determined that given Duke's relative size—that is, that most of our departments are smaller than those of our peers—and given the relative proximity of all of these on the campus…there could be real advantage to Duke to seeking to bring together resources from all parts of the University around intellectual problems,” said Provost Peter Lange, who was on the committee that issued the 1988 report—an associate professor of political science at the time.

Some of the interdisciplinary growth at Duke came through natural collaboration between faculty members in an open intellectual environment. Fields such as political science and economics were beginning to bleed into each other, creating a natural opportunity for cross-disciplinary activity, said Lange.

The cross-disciplinary activity which Duke’s collaborative environment has fostered is not limited to the social sciences. Dr. David Epstein, Joseph A.C. Wadsworth clinical professor and chairman of the Department of Ophthalmology at Duke Eye Center, explained that Duke’s collaborative environment has allowed him to make breakthrough discoveries and lay the groundwork for a clinical startup.

Epstein’s work with Eric Toone, leader of the Innovation and Entrepreneurship Initiative, led to promising new glaucoma drugs which were the foundation for Aerie Pharmaceuticals, a company founded by Toone and Epstein in 2005. The company went public last October, raising $60 million in capital.

“The biggest lesson is the value of interdisciplinary science at Duke,” Epstein previously told The Chronicle. “It never would have happened anywhere else except at a university where you can mix undergrads and graduate programs across different schools.”

Epstein specifically singled out Duke’s open intellectual environment as key to his collaborations.

“There are places where people do not want to collaborate because they think people will steal their ideas, where a professor of chemistry could care less about ophthalmology,” Epstein said. “The culture that we’ve got here—that we’d better not lose—is really unique.”

It was not until the late nineties, however, that Duke began to make a concentrated push toward becoming an interdisciplinary university. Strategic plans approved by the faculty and the Board of Trustees in 1994, 2001, 2006 and 2010 all emphasized the role of interdisciplinary programs. In 1993, the office of Vice Provost for Interdisciplinary Affairs was created, and in 1998, the position was made full-time.

“Most of our peers do not have full time positions for a Vice Provost for Interdisciplinary Studies,” said Vice Provost for Interdisciplinary Studies Susan Roth. “So that’s an important structural thing. You’ve got someone who’s in a position of some authority whose full time job is to focus on interdisciplinary studies. That makes a huge difference.“

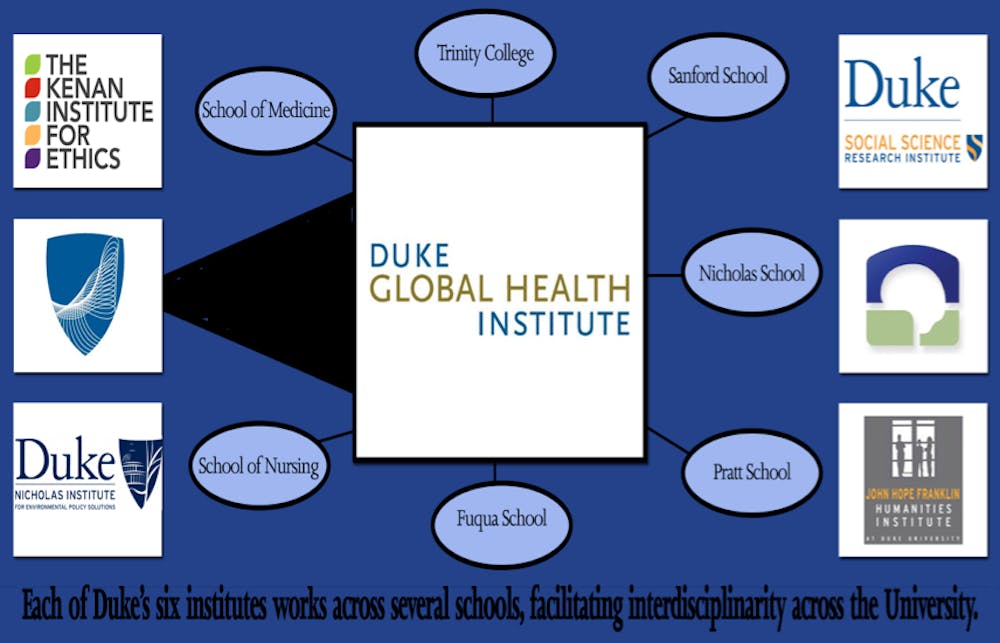

In 1999, Duke began to build a structure to accommodate interdisciplinary programs at a higher level with the creation of University-wide institutes. Beginning with the John Hope Franklin Humanities Institute—established to focus on interdisciplinary research involving the humanities—seven institutes dealing with subjects ranging from social science to genomics were created over the next ten years. This was the beginning of a larger structural shift in the university that would put less emphasis on traditional academic departments and focus more on interdisciplinary institutes as the future of education and research.

A foot in two worlds

While Duke's institutes are on the same level as other academic departments, they do not function in the same way, especially when it comes to hiring. Rather than using the standard model of a tenure track in the department, institutes get most of their faculty from joint appointments with traditional departments.

Joint hires “spend half their time in the institute and half their time in their school,” Roth said. “It’s been an incredibly successful program in terms of the kind of faculty we’ve been able to draw to Duke because they have an intellectual community that is broader than their discipline or their department and it’s incredibly intellectually stimulating.”

This method of hiring faculty provides benefits for both academic departments and institutes. The departments have another group sharing some of the cost of the new hire, while institutes get high-profile faculty in their organization.

“We help to recruit faculty who are outstanding, who are invigorated by the intellectual atmosphere of an interdisciplinary institute,” said Michael Platt, Duke Institute for Brain Sciences Director, noting that the institute has helped to hire or retain approximately 20 faculty. “And then we help to bring resources to the table to help departments make hires that they would not have been able to make. In some cases we do the same for retaining faculty.”

Overall, there are currently approximately 100 joint appointments across all the institutes at the University, Roth noted.

There are also around 500 faculty with some involvement in the institutes, explained Hallie Knuffman, director of administration and program development for Duke's Bass Connections. Multiple traditional departments can also make joint appointments between themselves.

A stable tension

Joint appointments are also one of the main sources of friction between traditional departments and Duke’s interdisciplinary structure. Faculty members who are working both in a department and an Institute are only able to spend part of their time in either organization.

“A lot of people are overcommitted,” said Michael Munger, professor of political science, economics, and public policy and the director of the Philosophy, Politics and Ethics program. “It means that some of what you would have if we didn’t have so many interdisciplinary commitments we’re giving up. The benefit is that there’s a lot more diversity for students and graduate students to choose from.”

Tensions in departments can also occur when professors on joint appointment and professors committed only to the department have differing visions of the work that the department should be doing. Departments may have an incentive to hire faculty who they would not otherwise hire because an institute will share the burden of paying the faculty member’s salary.

“It may distort and push the departments in ways they don’t particularly want to go,” said Michael Gillespie, professor of political science and philosophy. “They’re able to hire more people than they might have, but they have some of their core areas that haven’t been covered.”

Lange points out that when academic departments and institutes are forced to interact, there are bound to be tensions. He compared the current structure of the University to a matrix, with rows of traditional departments intersecting with columns of interdisciplinary institutes and many faculty members sitting at the junctures between rows and columns.

“If you learn anything about matrix systems, there’s always tension,” Lange said. “In fact, if the tension goes away, then either the rows have beaten the columns or the columns have beaten the rows, because the tension is inherent in the system. And you’ve just got to live with it, work with, it recognize it, remove the obstacles where you can, but there’s always going to be tension.”

Duke has taken some steps to ease this inherent tension. Perhaps most significantly, the University has changed the way that research grant money is divided up. Lange explained that grants generally give money not only for research but administrative costs. Before, this administrative money would go to an academic department, incentivizing departments to secure grants only for themselves. Now, administrative money goes to the school or college which contains the department, making it easier for researchers to collaborate across departments or institutes.

Platt also praised this model for handling grant money.

“That’s a really nice model because it ensures that there’s no competition between departments and institutes,” he said. “I think that’s really, really important because if we were competing over those dollars then there would be some tension.”

That does not mean that funding tensions don’t exist. Gillespie noted that although Duke’s interdisciplinary programs deliver benefits, they can cost traditional departments—not just in terms of faculty resources but financially as well.

“Basically the Provost puts a tax on all the departments and all the divisions and they pay money and then he puts money back into institutes, so it’s a top-down kind of decision making,” Gillespie said.

Of course, friction will become more apparent as interdisciplinary research and curriculum becomes more and more central to Duke. Munger expressed serious reservations about attempts to move away from a system where interdisciplinary units are tightly linked to traditional departments.

“Here’s the thing—I don’t want interdisciplinary programs hiring their own faculty. I want the faculty to come from the departments and then have an affiliation with the interdisciplinary program,” Munger said. “If they passed the hiring test of a traditional department and in addition the interdisciplinary program wants them, I think that’s the model Duke has had a special genius for.”

Ahead of the pack

As Roth noted, Duke’s peer institutions—including Harvard University, Yale University, Stanford University, Princeton University, the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Chicago—do not appear to have an office at the level of the Vice Provost or higher solely focusing on interdisciplinary activities. Duke's institute structure, University-wide and independent of departments, similarly appears to be unique. But with interdisciplinary research becoming more common, a number of peer institutions include some sort of structure for interdisciplinary work.

“Research, including the job of involving undergraduates in that research, drives a lot of the crossing of disciplines,” said Rob Nelson, executive director of education and academic planning at the University of Pennsylvania.

At both Penn and Harvard, interdisciplinary structures and organizations are created on an as-needed basis to accommodate research initiatives driven by faculty. The effects on undergraduate education or the overall structure of the university are indirect at best.

Harvard has a number of programs and centers which handle interdisciplinary activities, but all of them are subsumed within other schools or departments

“I think they fill a distinct need, but they fit very comfortably alongside the role of departments and schools,” said Kathleen Buckley, associate provost for science and director of academic affairs for interdisciplinary science at Harvard.

Bass Connections: A revolution in the making?

Both Lange and Roth said that in the future, interdisciplinary programs are likely to become a more integral part of Duke, both from a teaching perspective and a research perspective. One big step towards this integration is Bass Connections, which was funded by a $50 million dollar gift from Anne and Robert Bass.

Bass Connections programs, which were first run in Fall 2013, bring real world topics into classrooms and are integrated both horizontally between disciplines and vertically across different levels of students and faculty. Instead of having standard graduate or undergraduate courses, Bass Connections programs create teams consisting of graduate students, undergraduate students and faculty across different disciplines. These teams work on a number of different research projects related to a central topic and also take classes which involve knowledge from multiple disciplines.

Steven Blaser, Trinity '14, who participated in the Public Access to Government Information program, explained that his program is very different from any other kind of class he’s taken before

“At the base it’s different because you take very few classes that have undergraduates and graduates,” Blaser said. “Getting their perspectives on certain things that you guys are crafting as a group is invaluable and it’s really something you can’t get in many other areas of the university.”

Blaser said that in many ways, the program resembled a combination of independent research project and real world problem solving task force.

“You’re actually coming up with this information and then you’re presenting it to people that are actually relevant stakeholders,” Blaser said. “It might be an extended research project but it gets that practical component that I think really broadens what you’re able to do.”

Junior Christopher Zhang, a member of the Racial and Educational Inequality as a Consequence of Family Structure: Learning from Shotgun Marriages program echoed Blaser’s statement.

“It’s definitely very different from sitting in a huge lecture room where you barely have the opportunity to engage with the instructors,” Zhang said. “We not only learn from our professors, but we also learn from our team members.”

Zhang said he believed that Bass Connections were an extremely valuable research opportunity for undergraduates.

“It’s a very precious opportunity for undergrad students to get real firsthand research experience which they normally don't have the opportunity to have,” Zhang said. “You can really learn a lot from doing actual research. You’re not just reading the literature. You’re actually doing something. You’re making a difference.”

Duke administrators make no secret of their goals to expand Bass Connections and to use it to transform the University.

“I think what we hope for is that it’s not just going to be a program that sits apart in some way, like DukeEngage, that it really is going to influence how things routinely get done around the University,” Roth said. “So we have big ambitions.”

The Bass Connections program has expanded quickly, with 37 project teams operating during the 2013-4 school year and 41 more taking applications for the 2014-15 school year. Demand for the program has exceeded expectations, according to Knuffman.

Lange added that the impact of Bass Connections will be especially felt by students.

“I think curricularly—assuming Bass Connections succeeds—that’s going to leave a real mark on the learning experience of our students because it’s really going to bring the departmental or disciplinary learning together with interdisciplinary learning, it’s going to link what students learn in the classroom in a disciplined way to research projects,” Lange said.

Taking the next step

The future of interdisciplinary beyond Bass Connections is also unclear. Currently, the program is main focus of Duke’s interdisciplinary administrative establishment.

“I couldn’t say what’s after that because we plan on really pushing this very hard for a long time,” Roth said. “We feel like it is an opportunity to do something transformative.”

The future of the institute structure offers flexibility, as well. Each institute undergoes regular administrative reviews, and last year's review of the Institute of Genome Sciences & Policy led to the decision to dismantle the institute into three units. But interdisciplinarity is valuable no matter the form, administrators noted.

“Our interdisciplinary commitment, our global commitment, our knowledge in the service of society commitment and also the notion of engagement, both of faculty and of students, are qualities that have given Duke a really distinctive identity, even among our peers, and that’s an important thing to have,” Lange said. “We don’t want to just be copies, whether inferior or superior copies, and that we derive a lot of value from that.”

How the tensions in this transition are resolved is the major question left to be answered. Answering that question will take time and a willingness from everyone involved to expect and handle problems as they come up.

“These things take time. You don’t do it overnight, you don’t do it with one flashy appointment, you don’t do it with a single gift. There’s a lot of work,” Lange said. “That’s the way a great university is built, over long periods of time.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.