The University is currently conducting one of the most important administrative searches in the past decade.

When Peter Lange steps down in June, he will conclude his third term, making him Duke’s longest serving provost. During his 15 years in 220 Allen Building, he has been at the helm of dean appointments for each of the University’s 10 schools, the establishment of various research institutes and the creation of Duke Kunshan University, among numerous other projects.

The need to balance broad strategic goals with day-to-day management of a large research university makes the position a challenge for any provost.

“The provost is probably the most difficult job on the campus and probably the least appreciated,” said former Academic Council chair Arie Lewin, a professor of strategy at the Fuqua School of Business who has been at Duke since 1974.

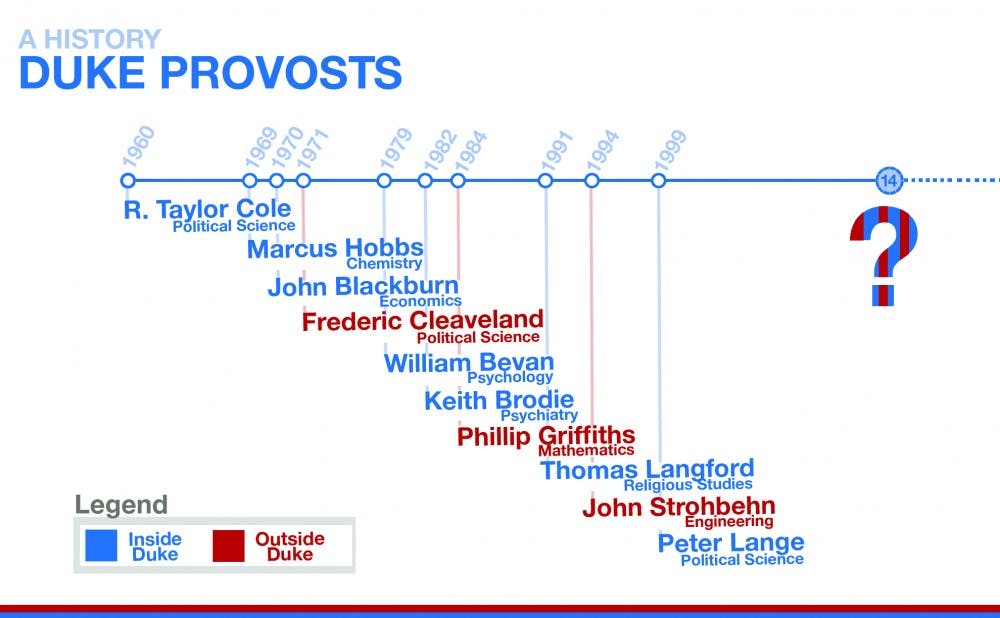

The significance of Lange’s time as provost becomes particularly apparent when considered in the context of the position’s history at Duke. Of the 10 men who have held the job, just four have had terms longer than five years, and Lange is the only one to serve for more than a decade. The length of his term is unique among peer institutions as well—he has served longer than any of his counterparts in the Association of American Universities, which comprises more than 60 of America and Canada’s leading research institutions.

Lange’s leadership style and character have distinguished him from his predecessors, colleagues say—and in the eyes of some, he is the best to have ever held the position at Duke. His legacy will now frame the search for a successor.

53 years of provostship

As the University’s chief academic officer and faculty leader, the provost reports directly to the president and determines the general direction of the institution’s scholarship.

“The president and provost spend three or four hours every week just talking to each other,” President Richard Brodhead said. “There’s no issue that comes up that we haven’t talked through.”

A provost’s responsibilities do not end with academics. Directly under the provost are more than 10 vice provosts, as well as the deans of Duke’s 10 schools. The provost is also responsible for policies related to financial aid, admissions, Duke University Press, DukeEngage, information technology, libraries, institute and initiative directors, the Talent Identification Program, the Nasher Museum of Art and digital initiatives.

“The president can’t do everything when it comes to running an institution, and so a place like this has to have a provost with real authority, who can be backed up by the president,” said Philip Stewart, Benjamin E. Powell emeritus professor of romance studies, who has been at Duke since 1972.

Former President J. Deryl Hart established the provost position in 1960 in an overhaul of the academic administration. The position evolved from a previous role known as vice president of the educational division. Political science professor R. Taylor Cole was the first person appointed to the job—serving nine years, second only to Lange’s 15. Among Cole’s most prominent accomplishments were overseeing the integration of the University and an increased commitment to graduate and professional education.

“He also had a great sense of humor, and that’s critical,” said James B. Duke professor of economics Craufurd Goodwin, who served as assistant provost under Cole. “The stresses and strains are remarkable at times, and when stuff hits the fan, it’s pretty bad.”

The position experienced relatively quick turnover in the years following Cole’s decision to step down in 1969. Chemistry professor and former dean of the graduate school Marcus Hobbs was the second provost. But Terry Sanford was announced as president shortly thereafter and chose to put economics department chair John Blackburn in the role, ending Hobbs’ term after just one year.

At the end of Blackburn’s first year, however, he took a different administrative role, making room for Frederic Cleaveland to become Duke’s third provost in three years.

A political science professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Cleaveland was Duke’s first provost to be hired from outside the University. In the role from 1971 to 1978, his term saw the merger of the Woman’s College with the Trinity College of Arts and Sciences and the beginning of initiatives to promote faculty diversity.

But it was under his successor, psychology professor William Bevan, that the University began to transition from a regional power to a national one.

“There are a number of people here who believe his provostship was the turning point in making Duke standards very, very respectable,” said E. Roy Weintraub, an economics professor who has been at the University since 1974 and former dean of the faculty of arts and sciences.

As provost, Bevan focused much of his energy on hiring talented junior faculty and also worked to standardize the rules for faculty appointment, promotion and tenure. The search for his successor proved complicated, however, and Keith Brodie—later the University’s president—took the role for a year.

Mathematician Philip Griffiths, from Harvard University, ended up in the position from 1984 to 1991 and continued to build on Bevan’s steps forward.

“The secret to [Griffiths’] success—which was considerable—was his cooperation with faculty,” Stewart noted.

Griffiths pursued a strategy of hiring high-profile senior faculty from other universities in order to have an immediate impact, rather than bringing in junior faculty and hoping they would develop into academic stars, said Bishop-MacDermott Family chemistry professor Alvin Crumbliss, who has taught at Duke since 1970 and is a former dean of the faculty of arts and sciences.

“Griffiths, coming from Harvard, was not averse to throwing a lot of money at people,” Weintraub said.

Although many praised his logistical skills and vision for the University, some noted that he did not have a background in administration and had a leadership style that was not conventionally personable.

“His goal was to make this an elite university, and that’s the style he adopted as provost,” Crumbliss said.

After seven years in the role, Griffiths was replaced in 1991 by Thomas Langford, dean of the Divinity School. Langford excelled at communicating with faculty, colleagues noted.

“He knew how to bring people together and was very inclusive and very thoughtful,” Lewin said. “He was also very good at finding compromises.”

Langford spent three years as provost—covering the transition from Keith Brodie’s presidency to Nan Keohane’s—before retiring. He was succeeded by John Strohbehn, previously the provost at Dartmouth College and an engineer by training.

Strohbehn served one five-year term, focusing particularly on undergraduate education and on building in the sciences. He did not have much experience with a large research institution such as Duke, which was sometimes reflected in his work, Weintraub said.

“He was a very nice man, he just didn’t seem to have much of an impact on things,” Goodwin noted.

Lange’s legacy

At the end of Strohbehn’s term, Keohane appointed Lange to the position.

“When Peter replaced [Strohbehn]… the immediate change was pretty obvious,” said Michael Gillespie, professor of political science who has been at Duke since 1983.

Lange had served as chair of the political science department and as a vice provost for academic and international affairs. He also served as one of the key architects of Curriculum 2000, the redesign of the undergraduate curriculum for the new millennium.

One of his priorities as provost was increasing faculty quality.

“That’s one thing about Peter, he clearly knows what it means to be an academic institution, what does it mean to have faculty who have a life of scholarship,” Lewin said. “It’s not just counting articles in top journals.”

As provost, Lange has also worked on increasing the University’s global presence—improving Duke’s international reputation and bolstering programs abroad. A key part of this effort was the establishment of Duke Kunshan University in China, set to open in Fall 2014.

“One of the things that Peter decided long ago was that in order to compete as a global university, we needed to have an international presence and this was the way to do that,” Gillespie said of Kunshan. “People differ about whether that’s correct or not.”

Initially, the venture met with criticism from some faculty who felt the administration had moved forward too quickly without enough time for discussion. Lange and the other project leaders responded by establishing more avenues for faculty input in recent years.

A similar dynamic arose when Lange signed a contract with Internet course provider 2U in Fall 2012 that would have entered Duke into a consortium of schools offering for-credit online classes. In April, however, the Arts and Sciences Council rejected a motion to accept online courses for credit, with a number of professors criticizing a lack of faculty involvement in the planning process. As a result, Duke was forced to back out of the contract with 2U.

“[Lange] hates to lose,” Gillespie noted. “He lost on the [online course] thing last Spring, but he’s approached that in sort of a good spirit in an attempt to get people to think about doing things that way.”

Keohane said Lange struck a balance between confidence in his own views and acceptance of other perspectives.

“He was quite willing to stand up to me when he disagreed with a direction I was taking, before a decision was made or announced and sometimes convinced me I was wrong,” Keohane wrote in an email Dec. 2. “But at least as often he was convinced instead, or was willing to accept my decision and work hard to implement it.”

In addition to greater international exposure for Duke, Lange has spearheaded a push toward interdisciplinary education, as seen in the establishment of Duke’s seven institutes. He has encouraged a system where there are few barriers between departments and schools in terms of research opportunities, Crumbliss noted.

Brodhead credited Lange with creating a deep culture of collaboration across Duke’s academic units.

“The deans at Duke work together in a way that they don’t work together at any other university I can name,” he said. “That doesn’t happen by accident. It’s been the result of endless work by the provost to make people realize that the parts work best when they’re parts of a whole.”

Lange’s colleagues spoke highly of his shrewdness, humor and balance of common sense and intellect.

“When you work for somebody like him, you want to do your best,” said Patricia McHenry, the provost’s executive assistant.

McHenry has worked in Lange’s office for nearly his entire tenure and plans to retire when he steps down.

Delegating is among Lange’s assets and he allows people to do their jobs with relative autonomy, Gillespie noted.

“Peter, I’ve always thought, was the perfect person to be provost, partly because he is probably the most gregarious person I know,” Gillespie said. “He loves to talk to people, and in fact, he’s a little bit uncomfortable not talking to people.”

Looking ahead

A 12-member search committee of faculty, administrators, trustees and students is currently working to find Lange’s replacement, who will assume the position in July 2014. The new provost will oversee the opening of DKU and grapple with the expansion of online learning and its effects on higher education.

Several professors expressed a preference for Lange’s successor to be hired from within the University.

“The problem with bringing somebody in from the outside is twofold—one, the people here don’t know what they’re going to do, and secondly, the people who come in don’t necessarily know where all the bodies are buried,” Gillespie said. “Peter knew where all the bodies were buried and where all the money was buried. Knowing where all those resources are, that makes a huge difference. And the upfront cost to somebody coming from the outside is pretty high.”

A person hired from outside the institution, though, can bring a valuable fresh perspective, Stewart said. But still others pointed to the University’s record of provosts, noting that the majority of the most effective provosts have come from inside.

“It’s a big gamble when you go outside, and we’ve found that in cases before,” Goodwin noted.

All in all, the role of provost is undoubtedly a complicated one. But when asked for the advice he would give his successor, Lange’s answer was simple.

“Love your job,” he said.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.