For 42 years, “Coach K” and “the rivalry” were intrinsically linked. Mike Krzyzewski dominated the Duke-North Carolina narrative, driving the competition and fueling the fire. Without his familiar face as the frontman, many have questioned the future of the rivalry. The 1,560 Duke students camped out in Krzyzewskiville, and the hundreds more who fell short in their hunt for that coveted real estate, disagree.

Just as the rivalry didn’t die with Krzyzewski, it was not born with him, either. Duke and North Carolina have been facing off on the hardcourt since 1920, and those first 60 years set the stage for the modern landscape of Triangle college basketball.

The two programs’ first matchup took place Jan. 24, 1920. Both true football schools at the time, basketball took a backseat in priority, funding and publicity for the first few years. The Tar Heels dominated the first decade, winning all but four 1920s matchups. Duke football head coach Eddie Cameron took over the program in 1929, guiding it into Southern Conference contention and the national spotlight. Cameron kept the rivalry competitive throughout his tenure, though he transitioned to the athletic director position following World War II. The early days of the rivalry were still heated and competitive, but not quite up to modern standards. It would be a few decades until that present-day hostility revealed itself.

A coach scorned

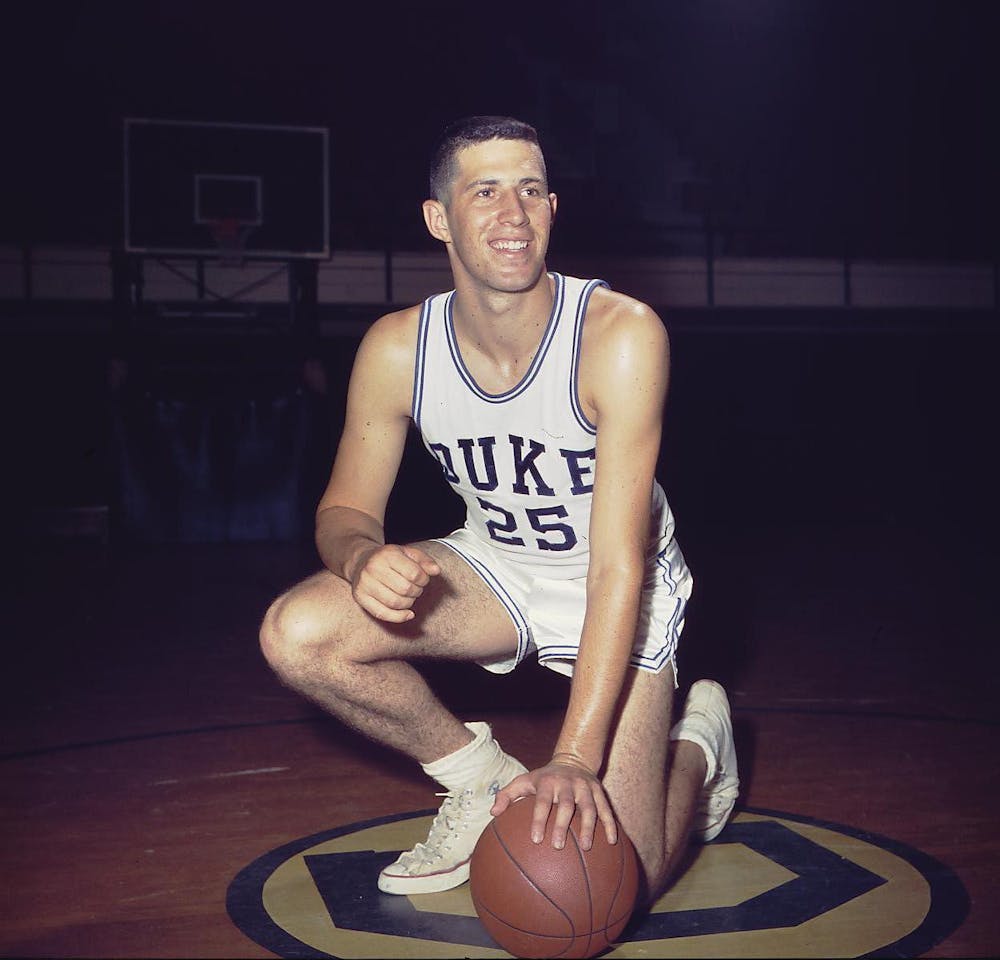

While Duke and North Carolina, fueled by their eight-mile proximity and perennial success, have always had an antagonistic athletic relationship, it was exacerbated in 1959. Tar Heel head coach Frank McGuire had firmly cemented his program atop the college basketball ranks, winning the 1957 national championship to cap off an undefeated season. The New York native dominated the Northeast recruiting scene, and Art Heyman was the player to get in the 1959 class. He had signed his national letter of intent to play for McGuire in Chapel Hill, but his family visit went sour. Heyman’s stepfather and McGuire got into an argument and Heyman decommitted from North Carolina.

“I had to step in between them,” Heyman said about the incident, per GoDuke.com. “My stepfather called Carolina a basketball factory and McGuire didn’t like that. They were about to start swinging at each other.”

Shortly after Heyman’s initial recruitment, Duke brought in Vic Bubas as its next head coach. Bubas was hired off of N.C. State’s staff where he had worked under head coach Everett Case for eight years. The Gary, Ind., native was an expert recruiter and continued to pursue Heyman despite his commitment, specifically targeting his family. His persistence paid off.

“He charmed my mother and stepfather,” Heyman said. “They made me go to Duke.”

McGuire’s failure to maintain one of the top players in the country, and the fact that he lost Heyman to his rival, drove the rivalry to new heights. When the Blue Devil and Tar Heel freshmen teams met in 1960, Heyman was punched in the mouth, an injury that required five stitches. The violence was indicative of what was to come, as the forward was soon to set the rivalry ablaze.

In the 1960-61 season, Heyman was starting for the Blue Devils as a sophomore. Duke had just won the ACC tournament before losing in the East Regional final of the 1960 NCAA tournament to NYU. The first Tobacco Road matchup of the season resulted in a 76-71 Duke loss. North Carolina’s Doug Moe shut down Heyman through the final 35 minutes. The Blue Devils took the loss personally, winning six straight and climbing to fourth in the AP Poll with a 15-1 record entering the rematch. The Tar Heels were ranked fifth at 14-2.

The game was ugly. With 15 seconds remaining, Duke led 80-75 after two Heyman free throws. North Carolina guard Larry Brown drove to the basket and was fouled by Heyman. That hard, likely unnecessary foul was enough to cause the tension to boil over. Brown threw the ball at Heyman and the two began exchanging blows. Both benches quickly cleared as policemen rushed onto the court to break up the brawl.

While the on-court violence is exemplary of both schools’ feelings toward the other, the events that followed feel familiar to anyone involved in the rivalry. Debate immediately ensued regarding the first punch, with much of the media claiming Heyman dealt the initial blow. Bubas’ response? The coach called a press conference the next day to play the footage of the fight for every media member in attendance, clearly showing Brown striking Heyman first.

“I think at that point Duke replaced [N.C.] State as Carolina’s archrival, and basically that’s been the case ever since,” journalist and longtime Duke expert Jim Sumner told The Chronicle.

“The Fight,” as it was coined, proved disastrous for both programs’ seasons. Heyman, Brown and Tar Heel Donnie Walsh were suspended for the remainder of the season. That season was McGuire’s last with North Carolina, as his recruiting tactics had gotten him into trouble with league administrators, resulting in NCAA probation for the Tar Heels. He resigned and was replaced with eventual North Carolina legend Dean Smith.

Back and forth

Though the Tar Heels would win the regular-season finale, defeating the Blue Devils 69-66 in overtime, McGuire’s departure set Duke off on a winning spree it would maintain for most of the 1960s. Through the 1965-66 season, the Blue Devils had won nine of the last 11 matchups, two of which came in the ACC tournament. Those two losses, though, were crucial for Smith’s career with North Carolina.

On Jan. 6, 1965, the Tar Heels fell hard to Wake Forest, their fourth-consecutive loss. Frustration with Smith had reached a breaking point. The team arrived back at Woollen Gymnasium after the beatdown to an effigy of Smith hanging from a tree outside. The hateful display sparked a fire under North Carolina—it hadn’t beaten Duke since the Tar Heels’ 1961 overtime victory, and had a quick three-day turnaround before making the eight-mile trek to Duke Indoor Stadium.

There, for the first time in his career, Smith and his unranked Tar Heels beat No. 8 Duke. They would repeat the feat a few weeks later in Chapel Hill. Smith had redeemed himself in the eyes of the North Carolina faithful. Two seasons later, he took his team to the first of three straight Final Fours, and while the Blue Devils still managed to pull off an upset here and there, the Tar Heels ruled the next decade of Triangle basketball.

The Foster rebuild

Bubas transitioned into administration in 1969. Bucky Waters and Neill McGeachy, his successors, kept the team afloat but neither could manage better than a fourth-place NIT finish. In 1974, Bill Foster arrived in Durham to try his hand at righting the fallen Blue Devil ship.

Foster kicked off his tenure by beating No. 8 North Carolina in the Big Four tournament.

It was an achievement he wouldn’t repeat for three years, but a proud accomplishment, nonetheless. Foster spent his first few seasons putting together the broken pieces of Duke’s program, bringing in strong players and setting up his crowning 1977-78 run.

Jan. 14, 1978 was the next time the Blue Devils downed the Tar Heels. Foster had perfected his squad, composed of junior Jim Spanarkel, sophomore Mike Gminski and freshman duo Gene Banks and Kenny Dennard, all future NBA players. In Cameron Indoor Stadium, Foster’s crew upset No. 2 North Carolina to cement itself in the conversation of top teams in the nation.

“1978 was, for the first time since maybe 1968, the programs were at parity,” said Sumner.

Though the then-13th-ranked Blue Devils fell to the eighth-ranked Tar Heels in the second matchup of the season, Duke then wouldn’t lose again until the national championship game against Kentucky, its first Final Four appearance since the Bubas days. The programs traded off their next five contests to close out the final two seasons with Foster at the helm for the Blue Devils. To replace him, Duke hired Army’s head coach with a long, Polish last name—and the rest is history.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Rachael Kaplan is a Trinity junior and sports managing editor of The Chronicle's 119th volume.