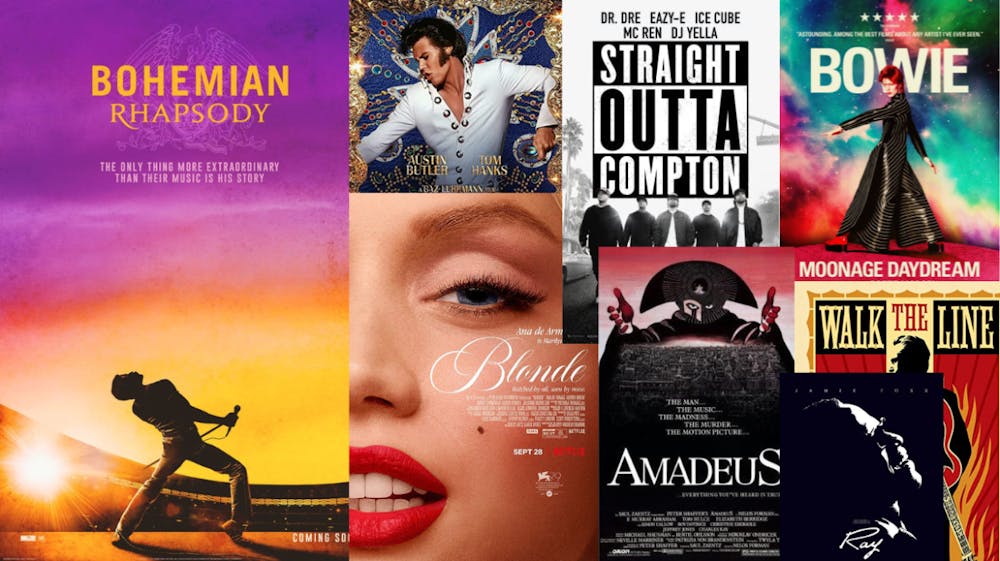

Four years ago, classic rock fans rejoiced in the debut of “Bohemian Rhapsody,” the blockbuster film rendering the breakthrough, achievement and dominance of rockstar Freddie Mercury and 70s juggernaut Queen. “Rhapsody” championed the box office and awards alike, garnering adoration from critics and fans, domestic and worldwide. It became the highest grossing biographical picture of all time, finishing in box office just a hairsbreadth from the billion dollar threshold. “Rhapsody” shattered and reset the biopic market, opening eyes to the earning potential of this genre.

Ever since, theaters and streaming services have shared a plethora of biopic films, namely “Rocketman” for Elton John, “tick, tick...BOOM!” for acclaimed ‘Rent’ playwright Jonathan Larson, ‘Elvis’ for…well, the king himself, the recently released bio-doc-music-video “Moonage Daydream” for David Bowie and Netflix’s “Blonde” for Marilyn Monroe. Each film has attempted, hoped, then failed to recapture the degree of financial and artistic success of “Rhapsody,” and yet, these films have still succeeded, either with critical-acclaim or one hundred plus million at the box office. Perusing the cinematic horizon, there is much biopic promise — from Naomi Ackie as Whitney Houston to Daniel Radcliffe as Weird Al Yankovic and Jonah Hill as Jerry Garcia. The future looks superstar bright. The days of the low budget, acting dependent, niche biographical film are long gone. Let me introduce the newest bankable genre: the biopic.

ARTISTIC RETELLINGS

In the last four decades of cinema, before financial or popular success, the biopic promised companies, filmmakers and actors a success not captured in dollar signs: prestige. In 1984, filmmaker Milos Forman swept the Oscars with “Amadeus” — a crazed and powerful portrayal of the life and genius of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. The musical biopic pocketed hardware for best picture, best director and best leading actor, among others. If you ever find yourself with three hours to kill, I highly recommend it. The soundtrack is, well, you can probably infer.

Two years earlier, all-world filmmaker Richard Attenborough similarly dominated the awards with “Gandhi” for the famed lawyer and ethicist. Biographical works on high profile figures established themselves as prestigious cinematic art, and key stakeholders took notice. “Amadeus” and “Ghandi” ushered an important precedent: biopics need not be accurate to achieve recognition for their brilliance.

In “Amadeus,” the primary storyline is the conflict between mediocre composer Antonio Salieri and the godly Mozart when no such conflict is likely to have occured. Also in the film, Mozart is a pauper genius, never achieving the financial success to match his unbridled and undeniable talent. When, in reality, Mr. Mozart lived quite the upper-echelon life.

As the century winded down and flipped, biopics continued to beget filmmakers an opportunity to celebrate historical icons in an artistic fashion. These excellent roles rocketed young actors and actresses to fame and stature: Denzel Washington was nominated best actor in Spike Lee’s “Malcolm X” and Russell Crowe likewise in the acclaimed best picture “Beautiful Mind.” Still, the biopic was stuck in an introspective phase. These are excellent movies, thoughtful movies, with nuanced and skillful performances, but they are not fun. Here enter the rockstars.

With musical celebrities, accompanying their name is their fame, talent, body of work and too often, their unfortunate demise at the hands of addiction or mental illness. Biopics had yet to realize the preheated storylines and interest baked into the lives of beloved musicians. The early 2000s cried No longer — these stories would be told. In 2004, up-and-coming Jamie Foxx played singer and pianist Ray Charles in “Ray.” “Ray” earned more than six figures at the box office and a best actor win for Foxx alongside a best picture nomination for the film. The formula writes itself: a preordained musical star embodied by an up-and-coming actor to play for us the genius and hardship of their melodic reign, the same formula that “Rhapsody’” would so nearly perfect fourteen years later.

The following year, up-and-comers Joaquin Phoenix and Reese Witherspoon were Johnny Cash and June Carter-Cash, respectively, in “Walk the Line,” earning an Oscar nomination for Phoenix and a win for Witherspoon. It was certified: the formula works. Music videos riddled these films. And why not? Separating lulls in the plot with classic, memorable tunes adds an untapped dimension to the films and provides writers with another tool to engage their audience. The music and film proliferated together, bathing a portion of the audience in nostalgia and a portion in fascination. Bingo.

Phoenix and Witherspoon sang and performed all their songs as well. #nolipsyncing. Wow.

“WHERE ARE WE NOW?” by David Bowie

We’ve re-checked the history. But how did we end up here, with “Elvis”, “Daydream” and “Blonde” back-to-back-to-back, all reaching astounding viewership? You might be inclined to jump right to “Rhapsody.” However, before biopics could reach Everest, they needed to conquer K2. That happened just three years earlier, when the second highest grossing biopic of all time was released to a smattering of positivity from critics and the bourgeois alike.

That film, with greater implication on the modernity of music than any other, is “Straight Outta Compton” — the rise of rap quintet N.W.A.

A personal favorite, “Compton” followed the formula perfectly and went beyond. After portraying his father Ice Cube in “Compton,” up-and-comer O’Shea Jackson Jr. proceeded with a notable career. And the music videos did what blockbuster musical films had never done before — swear a fuck ton.

“Compton” dominated financially, despite any notable international audience, by exploring a band and musical movement, equal parts revolutionary, relevant, controversial and adored. The real surprise, or perhaps travesty, was “Compton”’s poor awards turnout. Maybe the Academy isn’t one for rap.

“Rhapsody” followed and subsequently broke the formula. Rami Malek took a wonderful career to A-list status, showering himself in acclaim on the way, and youth culture will feel the implications for years to come.

Not to mention, there is nothing simpler than naming these films. Three options: the artist’s name, the artist’s most famous song or the artist’s most famous album. Easy as pie.

Each and every biopic —from “Amadeus” to “Elvis” — was an artistic retelling of the actual life of a real human being. In doing so, a film recaptures the intrigue and mystique that made these historic figures so iconic in the first place. A colleague of mine so eloquently described it as “an adaptation that observes accuracy for accuracy’s sake risks being boring.”

Still, despite the allowed leniency on accuracy, filmmakers and writers have a duty to celebrate the artist at hand. And celebration is not a direct equivalent to positivity. A biopic should celebrate the glories and sins, the wonders and disgraces of the human they are depicting. The new “Moonage Daydream” succeeds in celebrating the multi-faceted David Bowie. “Blonde” fails, presenting a one-dimensional Marilyn Monroe.

“Moonage Daydream” is far from a blockbuster movie and much closer to an extended music video filled with stunning behind-the-scenes footage overlaid with Bowie’s poetic voice-overs — put simply, something like a daydream. The medium of choice perfectly suits the life and art of Bowie, a varied savant of music, writing, painting, acting and theater. “Daydream” is the first officially sanctioned film on the artist by his estate. With Bowie as such a multifaceted artist and thinker, the complexity and movement of his life would be limited in a standard sequential biopic. His energy begged for the phosphorescent, intergalactic and randomly stunning sequences in “Daydream.” A Bowie fanatic may be left unfulfilled by the limited new information, but an inexperienced fan will appreciate the aura. A single, solitary qualm: cut twenty minutes. Why are recent projects so long?

YIKES. “BLONDE” IS TOUGH.

In the week since its public release on Netflix, you have likely heard something about “Blonde”. Likely, not something positive. There’s no need to dance with semantics. “Blonde” is cruel. Often appalling. Mind-numbingly stomach-turning. Now, cruel cinema is not necessarily bad cinema. Not always. But in “Blonde,” despite an impassioned and frankly terrifying performance from Ana de Armas, the message is nonexistent. There is no celebration of Marilyn Monroe. Only pain.

“Blonde” is narrow, examining Monroe for her body, mental illness and death, with little space left for her talent. Artistic liberties aside, a filmmaker has a duty to present, if not an all-encompassing portrayal, a well-encompassing one. People are a click away from the terms of Monroe’s overdose. What we desire, and frankly need to learn, is the breadth of her talent, her nuance… why is the subway grate photo the most iconic of the twentieth century? The why.

In the claustrophobic role, Armas leaves no doubt about her skill. The mirror scene is all goosebumps. Armas should play a supervillain, like soon.

The age of the blockbuster biopic is only an infant. Lodged in the growth stage, biopics over the coming years, musical and not, will nudge, reshape, and possibly restructure the market as this genre explodes in popularity. All-world filmmakers are turning their sights on biopics and at least one bomb looms in the distance. Get excited cinephiles, the future looks atomic.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.