Religious studies scholar Anthea Butler addressed racism in American evangelism, describing it as a feature and not a bug at Tuesday’s “UNIV101 Presents” webinar entitled “Religion, Race, and the Future of Democracy in America.”

Butler, who is the chair of religious studies at the University of Pennsylvania, was the featured guest in the latest installment of the UNIV101 speaker series. UNIV101 is a semester-long University Course designed to teach students about the concept and history of race. To highlight the pervasiveness of racial hierarchies across several disciplines, the course features guest lecturers from across Duke.

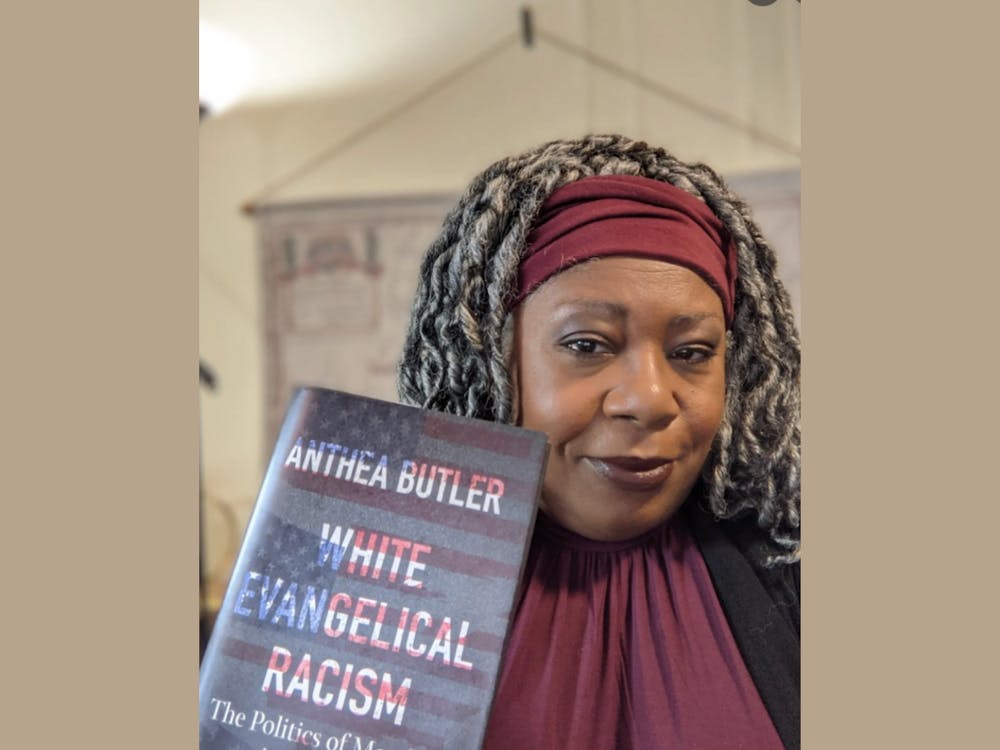

The webinar was co-sponsored by the Office of Undergraduate Education, the Duke Divinity School, Jewish Life at Duke, the Duke Wesley Fellowship, and POLIS: Center for Politics. It centered on Butler’s recently published book “White Evangelical Racism: The Politics of Morality in America.” Frank Stasio, former host of WUNC's “The State of Things,” moderated the conversation.

The pair started the event with a discussion of Evangelicalism’s history in the United States.

“Morality and purity came together in the South to make this very noxious mix,” Butler said. “One of the things that we should really consider is that this sacralization of virginity, of purity and all these kinds of things for evangelicals come out of these 19th-century ideas.”

Butler contended that racialized Christian doctrine, along with this history, laid the groundwork for the modern evangelical movement. She launched into a discussion on prominent North Carolina evangelist Billy Graham’s questionable record on racial issues.

“Billy Graham believed in maintaining order just like a lot of evangelicalism did,” Butler said. “He was not on the right side of things for a very long time,” Butler said. She added that Graham was well-connected to southern politicians, so he had to walk a fine line on racial issues.

Butler pointed to the Civil Rights Movement as evidence that white evangelicals selectively involved themselves in political battles to maintain a racial hierarchy.

“We don’t like to associate religion and violence, but I promise you, it goes together pretty well,” she said. “You get the letter from Birmingham Jail, and that letter comes from other white Christian pastors, who don't see fit enough to come out and support a cause that is righteous.”

Asked by a student attendee to define evangelism, Butler compared them to Christian fundamentalists, who believe that the written word of the Bible should be taken literally.

“Evangelicalism can think that too, but evangelicals are more apt to want to embrace culture, to think about music, to think about songs,” Butler said.

Discussing the rise of the evangelical coalition as a powerful political force, Butler dispelled the myth that abortion animated religious conservatives. Instead, she said, the first battle lines were drawn over the case of Bob Jones University, a fundamentalist Christian college that lost its tax accreditation for refusing to allow interracial dating in the 1970s.

“It’s culminated in the Texas state law [severely restricting abortion] that everyone’s trying to get rid of. This is the work of 40 to 50 years of evangelical advocacy; you have to look at it as the long game,” Butler said.

Later in the discussion, Stasio asked how Butler could explain former President Donald Trump’s support among evangelicals in light of his moral failings.

Butler cited Jeff Sharlet’s book “The Family: The Secret Fundamentalism at the Heart of American Power,” saying that evangelicals really wanted a strong man who they viewed as divinely anointed. They cared that "[Trump] would take care of the moral people, he could be an immoral man who cared for moral people, and they are the moral people. And so it didn't matter.”

Butler extended this argument to other authoritarian leaders like Indian prime minister Narendra Modi and Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro, who also excited religious fundamentalist bases.

Toward the end of the session, Stasio asked about Butler’s own experiences with race and religion.

“I wasn't thinking about the question, but I was living the question,” she said. To work for racial progress, Butler called for “real reconciliation.”

“What I would really like is a way in which people are really engaging with each other, and getting down to the heart issues,” Butler said. “But unfortunately, right now, it's really difficult to get down to the hard issues.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Anisha Reddy is a Trinity junior and a senior editor of The Chronicle's 118th volume.