Second in a series on use of force by Duke law enforcement officers. Read the first part, about the first use of deadly force by Duke law enforcement, and the third, a review of how DUPD officers have used force in recent years.

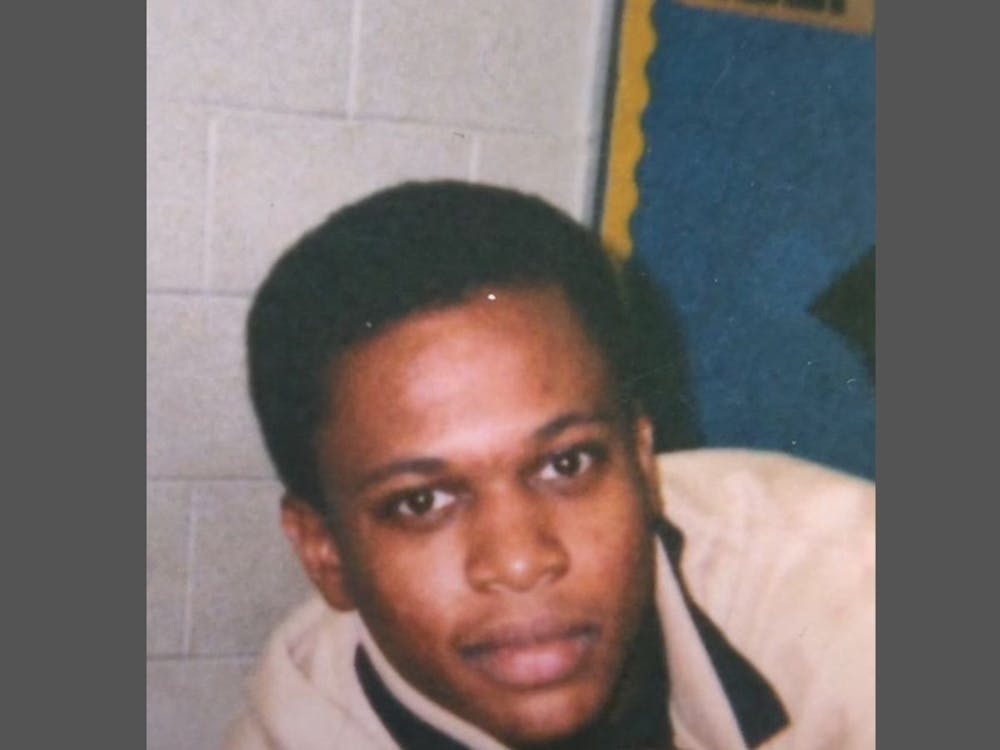

On March 13, 2010, Duke University Police Department officer Jeffrey Liberto shot and killed 25-year-old Aaron Lorenzo Dorsey of Durham.

DUPD Chief John Dailey told The Chronicle at the time that an officer had fired his gun one time after Dorsey attacked two officers and attempted to gain control of one of their guns, Dailey wrote.

Dorsey’s family filed a wrongful death lawsuit against Duke, Liberto and the other officer who was at the scene. The suit was dismissed, then appealed and dismissed two more times. The Chronicle’s coverage of the story at the time did not extend beyond interviews with and statements from representatives of Duke and DUPD, and The Chronicle neither covered the legal proceedings nor gave Dorsey’s loved ones a chance to tell their stories.

Amanda Mason, Dorsey’s fiancee at the time, reached out to The Chronicle last summer asking to share Dorsey’s story. She said in a later interview that after the shooting, she felt the story only came from the perspective of the officers—and not of Dorsey and “who he was.”

“The only thing that I want today is justice for him,” Mason said. “I believe he has a story, and I don’t want the story to just be pushed up under the rug. Just like Breonna Taylor has a story, Trayvon Martin got a story. Aaron has a story as well. And I want justice to be served.”

As a result, The Chronicle is revisiting the incident with the purpose of giving Dorsey’s loved ones a chance to share his story and their own, and of filling in the gaps in the paper’s coverage from over 10 years ago.

***

Liberto shot and killed Dorsey at approximately 1 a.m. on March 13, 2010, outside Duke University Hospital’s main entrance on Erwin Road and Fulton Street.

According to the court decision in a 2014 appeal filed by Dorsey’s family, Modrez Pamplin, a hospital security guard, received a complaint shortly before 1 a.m. from a family at the hospital about “a man panhandling near the entrance of the hospital.” The guard testified that he then asked the man—Dorsey—whether he was visiting someone at the hospital, to which Dorsey replied that he was not.

He testified that he then asked Dorsey to leave, and when Dorsey did not leave, the guard contacted the Duke University Police Department to report Dorsey as a “suspicious person.”

Larry Carter, the other officer at the scene, said in a deposition that he wasn’t sure whether Pamplin saw Dorsey asking for money or if a patron of the hospital complained to him that Dorsey was asking for money. He said that asking for money in front of the hospital is a crime and against Duke policy.

Carter and Liberto arrived at the hospital entrance shortly after 1 a.m. and asked Dorsey for identification, according to court documents. The officers testified that Dorsey turned away from the officers and started walking away, prompting Liberto to grab Dorsey. A struggle ensued.

In Liberto’s deposition, he said that after he asked Dorsey for identification, Dorsey patted his pockets, said that he didn’t have any and just said “Aaron.” Carter added that he saw a bulge in Dorsey’s left pants pocket and asked Dorsey if the officers could search him to make sure he didn’t have any weapons.

Liberto said that Dorsey patted his pockets and then “abruptly turned away” and started to walk around the bench with his hands in front of him. Liberto quickly ran up to him and “tried to gain control of his arms,” giving him something similar to a “bear hug” in an attempt to stop Dorsey’s actions, he said.

Liberto said that he believed Dorsey was going to grab a weapon at that moment “and use it against us or who knows what.”

Liberto, who said he was 6-foot-1, 230 to 235 pounds and bigger than Dorsey, said that as soon as Carter got within reach, Dorsey “broke [Liberto’s] grasp and grabbed on to Officer Carter’s pistol” with both hands.

Carter said that when Dorsey grabbed his gun, Carter proclaimed “He’s got my weapon—he’s getting my weapon.” He said that eventually he and Dorsey “[fell] to the ground” and both he and Liberto gave him commands to let go of the weapon.

Meanwhile, Liberto said that he was punching Dorsey in the head as hard as possible—to the point that he tore the ligaments in his pinky finger—but nothing that they were doing was having an effect.

“The punches aren’t doing anything. I escalate my force. I pull out my ASP baton, which I had not even used on duty before, but I’ve been trained with it,” he said. “I pull it out and I start hitting him with that, thinking if I can distract him, if I can get him to focus his attention on me, maybe Carter can recontain—you know, gain control of his gun. But he never looked at me, never ducked a punch, never anything.”

He said that as Carter and Dorsey were still fighting, he pointed the gun at Dorsey’s head and said, ”If you don’t stop and let go of that gun, I’m going to shoot you.” The first time Liberto pulled the trigger, the gun didn’t fire because it was pressed against Dorsey’s head. Liberto then pulled the gun back and fired again.

“I pulled the trigger because he was going to kill me and Carter,” Liberto said, denying that he pulled the trigger because Carter told him to shoot Dorsey.

Dorsey died at the scene. Liberto estimated that the whole struggle lasted around three minutes “struggling around on the feet, punching, hitting,” and 15 seconds on the ground struggling, he said.

Dorsey’s body was taken to the North Carolina Office of the Chief Medical Examiner in Chapel Hill for an autopsy and identification shortly after the shooting. Dorsey’s name, age and place of residence were identified four days later on March 17.

The autopsy report, which was released June 4, 2010, revealed a single gunshot wound that caused severe damage to Dorsey’s skull and brain, and a laceration and abrasion on the inside of his lower lip.

According to the report, Dorsey was 5-foot-4 and 180 pounds. The report noted that medical tests did not find any alcohol or drugs in his system and found no weapons—only two bus brochures—in his possession.

The incident was the second and last time thus far that Duke law enforcement officers have used deadly force, the first in the 1982 shooting of Danny Lee Winstead.

The State Bureau of Investigation began an independent investigation of the incident at DUPD’s request, and DUPD conducted its own internal administrative investigation.

Dailey told The Chronicle at the time that it was standard protocol for most agencies in North Carolina to have the SBI investigate “officer-involved incidents,” and that it was standard procedure for DUPD to conduct an internal investigation after an “officer-involved shooting.”

Following the SBI’s review, then-District Attorney Tracey Cline did not pursue criminal charges.

Under North Carolina law, an officer is authorized to use deadly force “to defend himself or a third person from what he reasonably believes to be the use or imminent use of deadly physical force.” Dailey told The Chronicle at the time that all DUPD officers are trained in when to use deadly force.

Dailey said that there was no evidence that Dorsey was a patient, employee or visiting family member or that the incident was gang-related.

In a December 2020 email to The Chronicle, Dailey wrote that Duke cooperated fully with the SBI’s investigation and the courts affirmed that the officers’ actions were “appropriate and justified to properly protect the safety of the public and themselves.”

He acknowledged the Dorsey family’s “pain and grief at the loss of a loved one.”

“This was a tragic experience for many—the witnesses, the officers but mostly for the Dorsey family,” he wrote.

Following the incident, The Chronicle reported that Carter and Liberto were placed on paid administrative leave “in accordance with procedure.” Dailey said that the department was working to make sure all officers, especially Carter and Liberto, received necessary support through an employee assistance program.

At the time of the incident, Carter had worked for DUPD for 23 years and Liberto had served for two. The News & Observer noted that as of June 20, 2012, Carter still worked for Duke and Liberto was a member of the Durham Police Department. In a December email to The Chronicle, Dailey wrote that as of 2020, neither officer was still with DUPD.

“One works for another police department and the other is retired,” Dailey wrote.

Despite an extensive search, neither Carter nor Liberto could be reached for this story. Dailey wrote that he did not have their contact information since neither works at Duke anymore.

***

The last time Amanda Mason, 34, spoke to Aaron Dorsey was two days before he was killed. She remembers him calling her and saying, “Hey babe, I’m at the hospital. I’m down here, they’re going to take me into the hospital. I love you, kiss our son.”

When Mason tried calling Dorsey later, her calls went straight to voicemail.

In February 2009, Mason and Dorsey moved from Detroit, Michigan, where they had grown up together, to Durham, North Carolina. She had given birth to a stillborn child in Detroit, and they were hoping to make a fresh start in the Tar Heel State. On Jan. 15, 2010, Mason gave birth to their first baby, Aaron Dorsey Jr., at Duke Hospital. They received a “best parents” superlative from the hospital ward, according to Mason.

Amanda Mason with her son, Aaron Dorsey Jr. Photo courtesy of Amanda Mason.

Dorsey’s mother died Jan. 25, which hit him hard. His mother was buried Jan. 30, and Dorsey returned to his home in Michigan for a couple weeks, before traveling back to North Carolina in February.

By this time, he was having trouble sleeping, Mason remembers, and so that’s why he was hoping to check in to Duke Hospital.

On March 17, 2010—the day Dorsey was identified as the victim—Mason heard a knock on her door from two police officers, who told her about Dorsey’s death. Dorsey, Jr. was just over two months old at the time.

Mason was shocked. Dorsey wasn’t the type of person who would attack police officers, she said. The police portrayed Dorsey as if he was a “monster,” she said, which “didn’t sit right” with her because she knew the type of person he was.

“Aaron Lorenzo Dorsey was my high school sweetheart,” Mason said. “A man that will take his shirt off to help anybody. A hard working man. A family man.”

She added that the police told her that there would be an autopsy report and asked whether he was on drugs or was drinking.

“When the autopsy report came back—no drugs, no alcohol. Aaron wasn’t the person that takes drugs or drinks alcohol,” Mason said. “We were born in Detroit, Michigan and that’s something we know not to do. We know not to attack no officer like they were saying or anything like that. He wasn’t raised like that. I wasn’t raised like that. And for the story just to be out there, it still makes me upset.”

Mason’s sister, Ashley Harrison, who is 32 and who, like Mason, grew up with Dorsey, added that Dorsey was always the cool kid who people wanted to spend time with, not somebody who would attack people or get in fights. In basketball games, he was the one who would break up the fights. He was a “mama’s boy”—lovable, with a beautiful smile.

“There's no way that his personality was this way and all of a sudden one night he snapped and tried to grab an officer’s gun. That really left us with a feeling like this not right….This can't be him,” Harrison said.

Dorsey was only about 5 feet 6 inches tall, said Anthony Deshawn Payne, Dorsey’s brother. He didn’t have an intimidating physical presence. He was like a “pencil,” Payne said.

“My brother sometimes could be a hot head, but it’s with family, it’s not outside, you know what I’m saying?” Payne said. He said Dorsey was always respectful and a “kid at heart.”

“This is not a person who is living on the street and looking for trouble,” he said.

When Dorsey was killed, Mason was “left in the dark” about many of the details of what happened, Harrison said. Mason didn’t have access to the full police report or evidence from the incident.

Mason said the police didn’t return any of Dorsey’s possessions, including his cell phone, which had all of their photos of baby Aaron.

Asked about Mason’s statement that she did not have access to the police report and the police did not return Dorsey's possessions, Dailey wrote that the DUPD “worked with Mr. Dorsey’s immediate family at their request and will continue to respect their privacy.”

***

Dorsey’s estate filed a wrongful death lawsuit against Duke, Liberto and Carter on Sept. 16, 2011, alleging that Dorsey was wrongfully killed.. The plaintiff, William Mills, administrator of Dorsey’s estate, sought damages, attorney's fees and costs as relief.

Payne said that he decided to pursue the lawsuit a few days following the incident because he knew that what the officers did was wrong and that the outcome “should’ve been something different.”

“My sister at the time was in Baltimore and I talked to her about it the first couple of days, when everything was fresh,” he said. “And I just was looking at the TV and a commercial came across and I said, you know what? I know this ain’t right. Let me go see if I can go get some type of legal help and see what went on.”

The lawsuit, which accused Carter and Liberto of employing “unreasonable and excessive force” against Dorsey, made three claims about the officers: negligence, assault and battery, and willful and wanton conduct.

First, the lawsuit claimed that the deadly force used by Carter and Liberto was “unreasonable and excessive.” The lawsuit also accused Duke of not adequately training officers in how to prevent the use of excessive force.

In its second claim, the lawsuit argued that Carter and Liberto’s conduct was an “assault and battery” on Dorsey that deprived his beneficiaries of “care and assistance, society, companionship, comfort, guidance, kindly offices, and advice.”

Third, the lawsuit claimed that Carter and Liberto acted with “deliberate, willful, and wanton disregard of Mr. Dorsey’s rights and privileges.”

The lawsuit also accused Carter and Liberto of fatally wounding Dorsey without “provocation or justification.”

Defendants Duke, Carter and Liberto responded to the lawsuit Nov. 23, 2011, denying all of the plaintiff’s allegations except for basic facts about Duke, Carter and Liberto. The Defendants argued that the plaintiff’s actions should be dismissed.

They asserted that the officers acted in good faith “without malice and with probable cause” and that Dorsey engaged in a manner that required the officers “to use reasonable force to protect their own lives and safety.”

The defendants filed a motion to decide the case without a trial May 2, 2013 on all the plaintiff’s claims. They alleged that the officers were “legally justified in using reasonable force to protect the lives and safety of themselves and other innocent bystanders,” were “entitled to public official immunity” and acted “reasonably at all times.”

The motion added that Dorsey’s actions during the incident “were the sole proximate cause of his death and constitute contributory negligence, barring recovery in this action.”

Paul Gessner, Durham County Superior Court judge, dismissed the lawsuit June 4, 2013, deciding in favor of the University for all claims. The Dorsey family appealed this judgement.

On June 17, 2014, a three-member North Carolina Court of Appeals unanimously upheld the initial ruling. The appeals court ruled that the officers’ actions leading to Dorsey’s death were not “corrupt or malicious, or… outside of and beyond the scope of [their] duties”—the only instance in which a public official can be held individually liable.

According to the appeal decision, both officers testified that Dorsey grabbed Carter’s weapon and would not let go’ even after Liberto hit Dorsey with his fist and a baton. Both officers testified that they believed Dorsey was an “immediate threat because he was pulling on the weapon, would not release it, and might have gained control of it.”

The court acknowledged that some witnesses expressed uncertainty about whether Dorsey’s hand was on the gun, but stated that this was because they could not see what was happening from where they were located and that most of the witnesses reported hearing Carter yell that Dorsey had a hold of his weapon—consistent with the officers’ testimony.

The plaintiff’s expert, Frances Murphy, a law enforcement expert with Fieger Law in Southfield, Mich., testified that he believed Dorsey grabbed Carter’s gun but only after Liberto had hit Dorsey with his fists and baton, according to the appeal decision. Murphy added that the reason Liberto shot Dorsey was because he was “inadequately trained” and “didn’t know how to break the situation up.”

“[Murphy’s] opinion was that the officers were trying to arrest Mr. Dorsey without legal justification and that, due to poor training, the officers used unnecessary force and Mr. Dorsey responded,” the decision read.

The Court of Appeals concluded in the decision that the plaintiff provided no evidence that Dorsey did not attempt to gain control of Carter’s weapon. It added that once Dorsey grabbed Carter’s gun, Dorsey’s response became excessive and unlawful. Had the officers managed to subdue Dorsey without deadly force, they “could have, and almost certainly would have, arrested Mr. Dorsey,” the decision stated.

Although the court also acknowledged that the plaintiff presented expert testimony that Dorsey’s hands were not on Carter’s weapon at the time Liberto shot Dorsey, it affirmed that the officer’s actions were not “corrupt, malicious, or… outside of and beyond the scope of [their] duties,” based on testimony from John Eric Combs, instructor for the North Carolina Justice Academy.

According to the decision, Combs testified for Duke that even if Dorsey’s hands were not on the gun at the time Liberto fired the shot, Liberto’s use of deadly force was justified. He said that the academy teaches that “any attack that includes an attempt to disarm an officer is a deadly force attack.”

“As far as a situation where two officers are around, an assailant grabs an officer’s weapon, my suggestion at that point is for the officer to do exactly what [Officer] Liberto did and use deadly force,” Combs testified.

Former SBI Agent Steven Carpenter also testified that the officers “very, very early in this struggle had every reason in the world to believe [Dorsey] intended to take that gun and harm somebody.”

“They were responsible for protecting a large number of citizens around them that night,” he added. “As a police officer they had a responsibility to protect those people, and, if anything, I don’t think they reacted quick enough to ensure that these people did not meet with serious injury or death.”

Following the appeals court decision, Dorsey’s family filed again in the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of North Carolina.

Defendants Duke, Carter and Liberto filed a motion to dismiss, arguing that “all of Plaintiff’s claims are based on underlying facts and contentions that have already been considered and dismissed in a prior state court action.”

The court granted the defendants’ motion and the action was dismissed Dec. 15, 2014.

Payne said that dealing with the lawsuit hands-on at the time was “very hard.” Having his sister in Baltimore at the time, dealing with lawyers and not having everyone on the plaintiff’s side seeing eye to eye on everything made it especially difficult.

“It was very hard for my family,” he said.

***

Today, 11 years later, Mason continues to be haunted by Dorsey’s death. She now lives in Detroit, but whenever she visits family in North Carolina, she can’t sleep. Seeing the news about Trayvon Martin and Breonna Taylor also brought the memories back, forcing her to relive the incident, Harrison said.

“I still wake up and it feels like it happened yesterday,” Mason said.

Aaron Dorsey Jr., who is now 11 years old, asks about his father all the time, she said. Sometimes, he wakes up at night screaming. She tells him to pray.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Mona Tong is a Trinity senior and director of diversity, equity and inclusion analytics for The Chronicle's 117th volume. She was previously news editor for Volume 116.

Chris Kuo is a Trinity senior and a staff reporter for The Chronicle's 118th volume. He was previously enterprise editor for Volume 117.