Di-Ding. “Urgent Message from President Price Regarding COVID-19 Plans”

Click.

“To the Duke Community…” Skimming. “Duke University and Duke Health will remain open, and many of our operations and activities will continue…” Scrolling. “Duke is committed to maintaining our daily operations, completing the semester…” Okay, okay.

“First, all on-campus classes will be suspended until further notice, and we will transition to remote instruction…” What? “Second, all undergraduate, graduate, and professional students who are currently out of town for Spring Break should NOT return to the Duke campus if at all possible…” Huh???

March 10, when President Vincent Price sent out the above announcement, was a historic day for Blue Devils. Many students casually exchanged goodbyes before taking off for spring break, thinking they would see each other in just a week—only to realize days later that their time on campus had come to an abrupt end. Some would never walk across the quad as a student again.

The moment also signified the start of Duke’s uphill fight to adapt to life in the era of COVID-19, a battle that is far from over. From transitioning to online classes to socially distancing on campus in the fall, Duke has bid farewell to its familiar self for the foreseeable future.

To recount how this all began, we interviewed a number of Duke students. These are a selection of the stories they told: stories of ruptured plans, frantic texts, unexpected relief, a life-altering email. Stories that are each, in a way, our own.

———

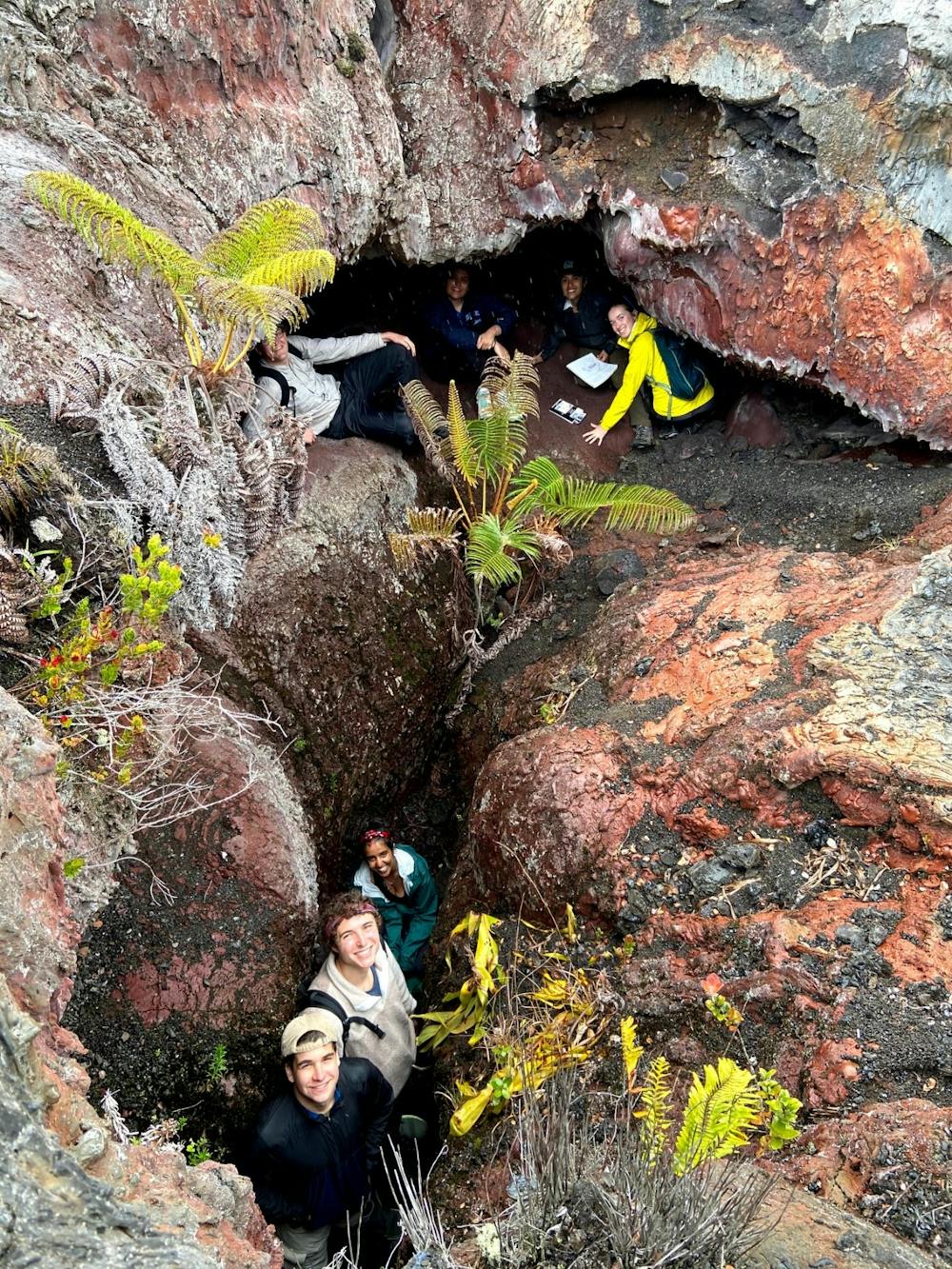

March 10 came early for first-year Anya Gupta, who woke up at 6:45 a.m., Hawaii-Aleutian standard time. (The class years given in this story are students’ class years when the events took place.) But adrenaline soon jolted her body awake. Today was a big day: She and her classmates would be exploring the Kilauea volcano on the southeastern shore of the Big Island, the largest of the Hawaii archipelago. Five days ago, they had embarked on a spring break trip for their Volcanology of Hawaii class. Today, for the first time, they’d be guided by Don Swanson, a research geologist for the United States Geological Survey and a legendary volcano aficionado whose career stretched back to the Sputnik era.

In her tent, Gupta rummaged for her gear: a North Face rain jacket, her gray Osprey backpack and a yellow notebook and mechanical pencil to write down her observations. She surrounded her dark hair with a hat she had bought at Yosemite. Soon, she and her classmates and professor packed lunches and piled into a van to drive from their campsite to the parking lot of the Kilauea Visitor Center, where Swanson joined them.

Puffy white clouds floated above Gupta and the group as they arrived at the Kilauea park. The baby blue sky that held them began just above the horizon, melting into azure. The air was warm, drenched with moisture and the smell of sulfur.

Gupta and her classmates spent the rest of the morning and early afternoon at the park, toppling over gray and black volcanic surfaces, plunging past yellow ferns that clung to the sides of narrow fissures, snapping photos of brown rock formations that rippled like the underside of a cow’s udder. They observed green crystals, spatter ramparts, lava trees. As the day wore on, the clouds grew thick and gray; rain occasionally pelted the ground. The only other sounds came from the laughter of the group and Swanson’s lecturing about volcanoes.

Around 4 p.m., the group finished their last field observations and headed to the nearby Volcano House hotel. Still dripping from the rain, they drew looks from the guests in the sparkling lobby. Gupta and her friends didn’t care, though; they had come for two precious commodities—cheap coffee and free Wi-Fi.

The hotel coffee was black and bitter, so Gupta dumped some extra sugar in hers. Then, she and the other students hurried over to the charging station, where they huddled over their phones, hungry for notifications. Wi-Fi had been scarce to nonexistent throughout the trip, so this would be a bonanza moment.

Gupta connected to the hotel’s network. Immediately, an email from President Price chimed in her inbox.

———

After breakfast, senior Elena Puccio drove with her family from San Ignacio, a small town in western Belize, to Placencia, a fishing village at the southern tip of the country. Puccio’s 18-year-old sister, Mia, was home in Virginia because she was in school.

Puccio’s dad was on his phone, furrowing his eyebrows, for most of the car ride. He is the medical director and chairman of the emergency department in the Inova Loudoun Hospital in Virginia. Family vacations are usually his one respite from his all-consuming job, but one coronavirus-related crisis after another would soon demand him to leave Belize early.

The family made a pit stop at the Inland Blue Hole for a swim at 11:30 a.m. local time, arriving at the resort two and a half hours later.

Puccio spent the next few hours unpacking and walking on the beach. She then settled in a cabana with her laptop, answering emails and working on an assignment due shortly after spring break.

As a front-line worker who had been watching the health crisis escalate since the fall, Puccio’s dad told her that her college graduation would certainly be canceled, if not in-person classes as well. Puccio brushed off the warning, unable to let her mind consider such a tragic loss.

At 5:54 p.m., her friend Ethan texted her: Idk if you heard but rumor is Spring Break extended by two weeks

5:55 p.m., Puccio: WHAT

6:01 p.m., Elena: Helloooo what do u meannnnb

6:08 p.m., Ethan: Sorry was driving

Classes cancelled for two weeks after break

Online classes only I think

6:23 p.m., Ethan: Check your email

———

Chaos reigned in Carly McGregor’s living room even before she learned the second semester of her senior year would be cut short. Eleven members of her Christian a cappella group, Something Borrowed Something Blue (SBSB), were sprawled across her Columbia, S.C., home, where they planned to spend much of a weeklong spring break trip focused on group bonding, prayer and performances for the community.

That day, SBSB awoke on a jumbled assemblage of leather couches, air mattresses and beds, then trickled downstairs to make pancakes. After breakfast, they crammed into McGregor’s “Scrabble room,” affectionately named for the board-game design McGregor and her dad painted on the ceiling when she was 12—four to a sofa, three to a chair, with the rest filling in on the floor. McGregor loaded a Google Slides presentation onto a TV screen.

This was McGregor’s “life story,” a hallmark of SBSB’s annual trip. Each SBSB member prepares an elaborate, sometimes hours-long, summary of their life, displaying accompanying images (a baby photo, a weathered picture of an ancestor, a portrait with a prom date) as they speak. McGregor’s life story, the last of four she’d give as a SBSB singer, was 233 slides long.

After another member led the group in prayer, asking for courage for McGregor to speak freely about her experiences, McGregor started talking. Clicking through the constellation-themed slide deck, she revealed her Myers-Briggs type (INFJ-T), her early artwork and pictures from her parents’ wedding. She described her home church, her first forays into music, some romantic escapades. About 90 minutes later, she wrapped up and fielded questions—some silly

(“What’s your favorite color?” “What hue?”), others serious (“Where do you want to be in ten years?”)—from her arrayed friends. Then the group piled atop McGregor in a group hug, the air mattress they sat on groaning in protest.

SBSB was running late (as always, McGregor said) to their next engagement, a performance at McGregor’s elementary school. On the way out the door, they slapped lunch meat on sandwich bread and tossed each other clementines for the road. Crammed like sardines into three cars, they hummed and vocalized through the drive to warm up their voices.

The crowd of 80 or so third-through-fifth-graders eagerly welcomed them. SBSB performed a five-song set, pivoting from a Whitney Houston cover to a moody contemporary Christian piece to gospel. Before the finale—an uproarious call-and-response take on Bill Withers’s “Lean on Me” for which members welcomed teachers to the stage—audience members posed earnest questions on everything from Duke’s workload to beginner beatboxing. SBSB high-fived the kids on their way out, giving an extra moment to one little boy in a Blue Devils basketball jersey.

After lunch, the group scattered to the winds. Some stayed home to nap, play cards or catch up on schoolwork; others drove to the mall and tried on silly outfits. Two of the boys, dismayed by the dearth of salad materials, headed out for groceries. By evening though, SBSB found their way back to the house, many clustering, rapt, around a game of Monopoly Deal being fought out on the living-room floor. People were talking in vague tones about dinner: The plan was a pasta bake and green bean saute.

At 7:24 p.m., right as the card game was rising to its crescendo, SBSB’s general manager looked up from her phone. “Guys,” she said, “we just got an email.”

———

When junior Laura Benzing joined her family for spring break, they soon thought of her as the resident coronavirus police. She had earned the title from the copious amounts of hand sanitizer she had applied to hands, door handles, refrigerator surfaces, bathroom faucets and the like.

For spring break, she had joined her boyfriend, parents, aunts, uncles and grandparents at Jekyll Island, a relatively isolated island off the coast of Georgia with “jungle sort of vibes,” Benzing said. Benzing’s family wasn’t taking the novel virus too seriously, even though they were the “prototypical at-risk group”—her mom is immunocompromised and her grandparents are in their 80s. That left Benzing as the family’s sole protector against an invisible and potentially life-threatening enemy.

The morning of March 10, Benzing and her family took a Jekyll Island tour, which required them to enter buildings, touch stair banisters and gather in tight places. For Benzing, the tour was “pure chaos,” a minefield of potential coronavirus transmission in a time when six feet wasn’t even in the vernacular yet, she said.

Benzing did her best to control the chaos. Before the tour guide handed out the earpieces to her family, she intercepted them and managed to lather them with Clorox and Purell. At every stop, she forced her family to wash their hands, drawing some looks from the other tourists. She also doused her family members with wintergreen isopropyl alcohol, and, from then on, wintergreen became the scent of the week for the Benzing clan.

Parts of the experience felt foreign. At one point, Benzing went up to a hot dog stand and realized that she had no idea how to navigate the situation. Was the hot dog clean? How to add condiments without contaminating everything? A bottle of ketchup might be swarming with spiky, microscopic spheres.

When Price’s email arrived later in the afternoon, Benzing, who had been stressed for most of the day, immediately felt relieved and validated. “I’m going to continue doing what I’m doing,” she thought.

Her family also took notice: no more griping about the sanitizer.

“That's what the email did,” she said. It changed her from the coronavirus police to the family’s “corona queen.”

———

Sophomore Nicole Moiseyev was in her local Whole Foods when the email arrived. Before the spread of the coronavirus pandemic, Moiseyev had planned on spending spring break in Spain. Instead, she headed with her friends to her hometown of Closter, N.J.

This evening, she and her friends had come to the grocery store to try to buy ground beef to make meatballs. Moiseyev, a self-described Whole Foods fanatic, noticed that the store was packed, thronging with people who pulled item after item from the shelves. The ground beef had disappeared, so had baking flour (thankfully, the toilet paper frenzy had not yet set in). Disappointed, Moiseyev and her friends headed to the kombucha aisle. They were in that aisle when President Price’s email arrived.

When she read the email, Moiseyev panicked. The world felt suddenly uncertain.

She proceeded to buy all the remaining teas of her favorite flavor. Who knew if she’d ever have the chance to buy them again?

That night, Moiseyev returned home with a shopping bag bulging with a dozen lemonade kombuchas.

———

SBSB had planned to return to campus at the close of spring break, but now members were trying to book flights and debating whether to cut the trip short.

“Everyone was breaking off into different rooms to call their parents in various languages,” McGregor recalled.

McGregor, realizing her final semester on campus had just concluded, ducked into a bedroom to cry as goodbyes to friends, spring Gardens strolls and SBSB’s annual WaDuke tea went up in smoke before her eyes.

The evening continued to unfold, a few members gathering in the kitchen to cook, others still on the phone with friends or significant others, and so did McGregor’s grief.

“Different parts of what it meant would just hit us,” she said. She’d been sad that she and a friend missed out on E-ball tickets, but it struck her now that she could never have gone anyway. Then, remembering SBSB’s unfulfilled album contract, she panic-dialed the producer to explain why the group couldn’t record in person.

Late that night, the singers packed into a single bedroom, talking quietly and picking out songs on the ukulele. The following day’s itinerary included a church gig in a Charleston suburb—as it turned out, McGregor’s final performance with SBSB— but this plan felt suddenly gauzy, unformed. Should we just go back to Duke to grab our stuff? One of the guys, an RA, said his sources didn’t think the dorms were even open, nor had most of SBSB settled on a method of getting home. (In reality, students did not immediately lose access to dorms, as was made clear in later emails outlining campus access and then further curtailing access.)

They’d do the concert in the end, reassured by the knowledge that they’d kept out of big cities and virus hotspots. But for now they filtered one by one from the warmly lit room back to their beds, the music and laughter fading slowly into the sweet Carolina breeze which kept whistling above and around them.

———

6:23 p.m., Ethan: Check your email

6:24 p.m., Elena: I sAw

At 6:18 p.m., Puccio received Price’s email, confirming what her dad had gently warned months ago.

7:07 p.m., Elena: Dude

Spring show

I’ll never sing my senior song

I might never rehearse with [Out of the Blue] again

7:22 p.m., Elena: I think my dad is flying back early

7:23 p.m., Ethan: Rop

7:23 p.m., Elena: I’m so sad

I planned so many things

For the rest of Puccio’s time in Belize, she could only fall asleep with the help of Benadryl and consistently woke up at 4 a.m., thinking nonstop about the abrupt end to her time at Duke.

“I’m not an emotional person at all, but I was so sad. I hadn’t been that sad in a very long time,” she said.

Puccio is a firm believer in working hard in the beginning in order to enjoy the end. Having overloaded throughout college except for freshman year and while studying for the MCAT, the chemistry major had intended to make her senior spring her best semester.

There had been so much to look forward to. She was supposed to perform in her last spring show, which she painstakingly planned as a cappella council president. She would have sung her only senior song—“Valerie” by Amy Winehouse—a solo at the last Out of the Blue performance. She had yet to play for the last time with the Duke Symphony Orchestra in Beaufort, S.C. She was going to finally present her research for the first time at the American Chemical Society Conference. She was set to make her debut at Beach Week and finally visit Asheville with her best friends at Duke.

“I’m really big on last times, for the sake of closure, and I feel really uncomfortable when I didn’t know something was the last time and didn’t appreciate it for what it was,” Puccio said. “It was very topsy turvy, trying to remember my college experiences and relive them with the realization now that they were my last time. My last lecture, my last time hanging out with my friends at Duke.”

———

Huddled together in the lobby of Volcano Hotel, Gupta and her classmates scoured the email from President Price. Many in the group began frantically calling their family and friends. Others hugged each other and cried. Gupta called her dad. “We’re not going back,” she told him.

Gupta felt particularly sad for the seniors in the group, one of whom was from Pakistan. She, along with the other seniors, had lost the opportunity to say goodbye to her Duke friends.

“I remember feeling like crying, but nothing came out,” Gupta would later write in a journal entry about the day. “I was in a state of shock—everyone was.”

The hotel lobby had a wide window that gave guests a view of a massive, gray crater. Gupta watched wisps of sulfurous gas rise from the crater and dance between sheets of rain. At least, she thought to herself, she had heard the news here.

Eventually, Gupta and the group left the hotel and took the drive back to their campsite, their spirits as soggy as the wet sky. It was “lots of questions, lots of interactions with our professor, asking, ‘What’s gonna happen?!’” Gupta wrote in her journal.

But their spirits rose as they got back to camp and prepared a dinner of pasta with chicken and vegetables, along with Oreos for dessert. Gupta helped cut the zucchini. Occasionally someone would mention the email—accompanied by a chorus of “What are we going to do?”—but mostly they avoided the topic. There were still five more days left in Hawaii, and they would make the most of it, email be damned.

During the rest of the evening, they played Avalon, a card game, laughing loud in the dark—loud enough that their professor, who had turned in early, kept hollering for them to keep their voices down.

“March 10 was THE most incredible day of field geology of our entire trip, and one of my favorite days of being in Hawaii,” reads one of the closing lines of Gupta’s journal entry. “It was also the most emotional day, knowing that life would arguably never be the same.”

Once the laughter had died down, Gupta climbed into her tent, which she shared with a couple other classmates. It was warm inside. She found her purple sleeping pad and slid inside her black sleeping bag. But then she remembered that she had borrowed both of them from her friends at Duke—friends she wouldn’t be seeing again for a long time. That night, she fell asleep thinking of them.

Correction: An earlier version of this article misstated the reason Puccio's sister was not with the family on vacation. It has been updated to reflect that she was home because she was in school. The Chronicle regrets the error.

Editor's note: Margot Armbruster, one of the authors of this article, is also an opinion managing editor for The Chronicle.

Mona Tong and Charlie Zong contributed reporting.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Margot Armbruster is a Trinity senior and opinion editor of The Chronicle's 117th volume.

Chris Kuo is a Trinity senior and a staff reporter for The Chronicle's 118th volume. He was previously enterprise editor for Volume 117.