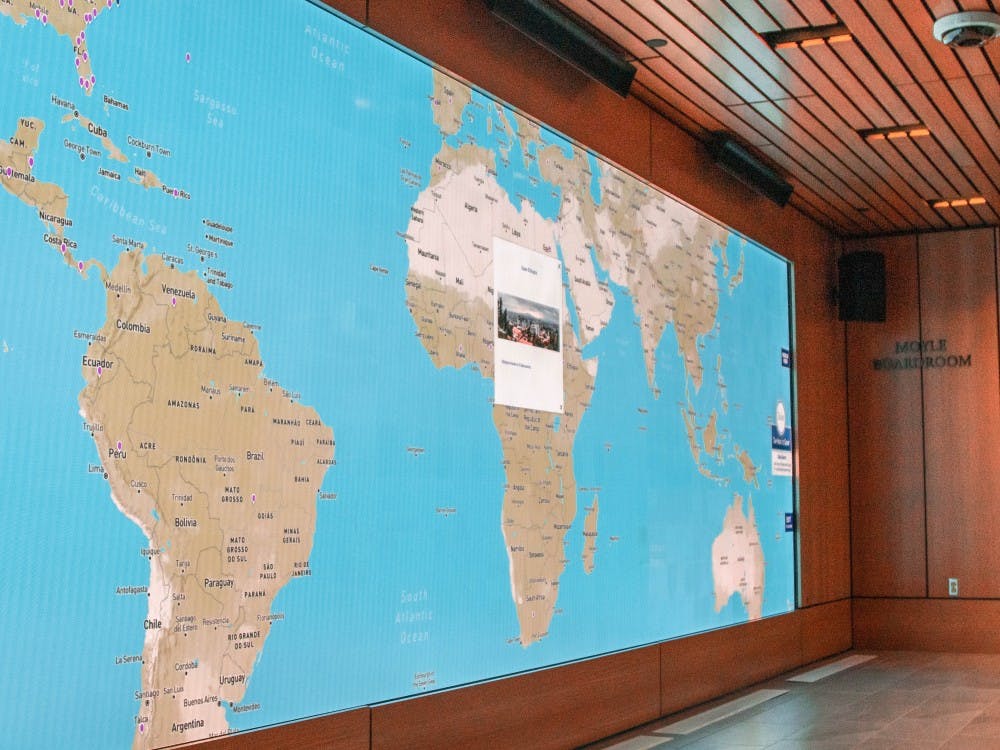

The recently opened Karsh Alumni Center just changed its portrayals of African and Middle Eastern countries. The portrayals were perpetuating stereotypes of Africa and the Middle East, using images of people in huts and riding camels in the desert—meanwhile, these regions are home to some of the largest and most advanced cities in the world. For an institution that touts diversity as an ideal, these portrayals were hypocritical.

What happens when only one narrative is told about a group, and what are the ramifications? When thinking about any place, we tend to think of its branding in the global consciousness. America represents freedom and democracy. France represents artistic culture and good wine. Africa—a whole continent—represents colonialism and poverty.

These ideas have wormed their way into our minds because of the stories told about them. In our culture that prizes practicality, we often forget that the creative and emotional aspects of life can equally sway the world. Stories, which we so often see as solely entertainment, are inherent and necessary to the human experience.

We don’t diffuse stories about just national identity. Why do we love the Hero’s Journey? What is so appealing about the call to adventure, the rising stakes, the “low point,” and the cathartic return to a new status quo? The story formula mirrors our own lives. Like heroes in fiction, we face obstacles, adapt to new situations, and even defeat antagonists in our daily reality. Narrative is not only global—it is intensely personal.

There’s a reason why narrative language pervades modern culture. We read between the lines, read someone like a book, read too far into something. Personal growth is character development. Vacations are a change of setting. In our digital world, we literally project snapshots and video clips onto our Facebook and Instagram “stories.” Stories give us a guideline for what we need to do to lead a fulfilling life. We learn from characters’ mistakes and successes. Who hasn’t pretended to be a favorite character growing up?

Regardless of stories’ influences on us, however, they are often relegated to the realm of frivolous entertainment. Many people speak with pride on not having to read books anymore. They talk of how they can’t watch a TV show until after classes are done. They avoid theater productions, finding them dry and pretentious.

The academic hierarchy also persists. As this column from the Chronicle details, in the wake of the Enlightenment, “subjects such as history, English, literature—became associated with “subjectivity” and thus “unprovable” in an academic world focused on empirical objectivity.” We value majors in the hard sciences for their job security and high salaries, but also because we believe they offer a more valuable contribution to the world.

Although stories often have the purpose of escapist entertainment, this is not to say they have no value beyond distraction. Everyone has a story that they cite as having influenced them in some way. Just because our relationship with narrative is often in the abstract, that relationship still gives us a context for relating to others.

This brings me to one of the main benefits of a narrative form: stories encourage empathy. To immerse ourselves in a narrative, we often literally take the perspective of another person, fictive or not, and live an experience through their eyes. Everyone has an experience that they love to share. Understanding and connection come from listening.

Seeing how stories encourage empathy can lead us to see why the portrayals in the Karsh Alumni Center were problematic in the first place. Continuing to push a single, inaccurate narrative about the lack of development in Africa and the exotic adventure of the Middle East leads to pity, not empathy. Instead of relying on caricature, narratives should be an authentic representation of a group’s experience, something which actually encourages the viewer to “be in their shoes.”

In the end, our whole history and our individual lives are just stories. We live experiences, observe plots and subplots, find twists in the storyline. We want to recount those lived experiences to others, to leave a mark and prove that like any character, our existence mattered in the world.

Ami Wong is a Trinity sophomore. Her column, “the bigger picture,” typically runs on alternate Fridays.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.