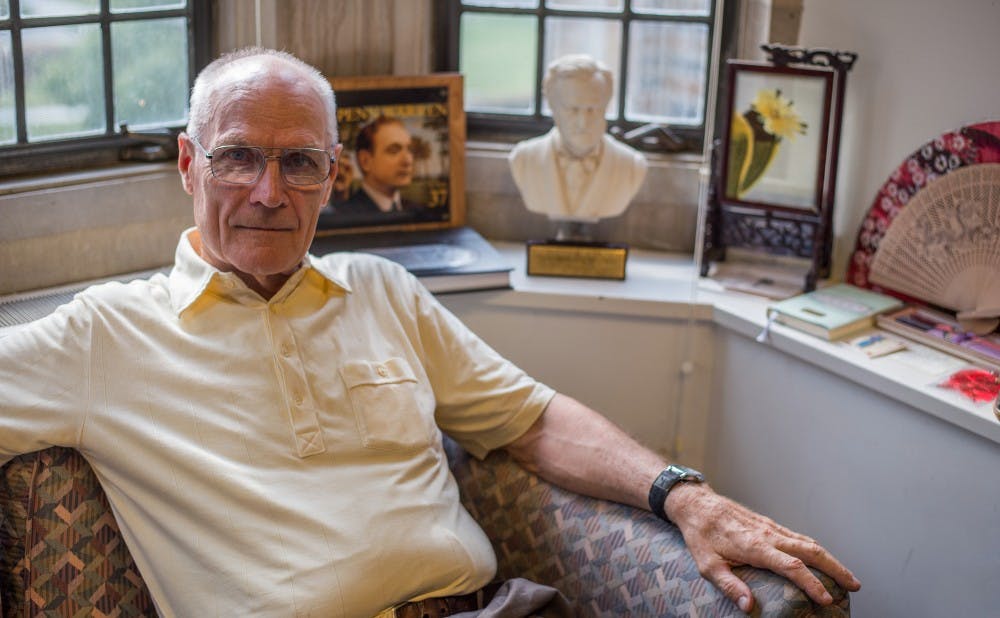

Victor Strandberg is a professor of English who has taught at Duke for more than 50 years—since 1966, to be exact. The Chronicle talked with him to discuss how Duke has changed, how Strandberg got his start as a professor and the famous students he's taught. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The Chronicle: What has it been like to teach at one school for so many years? How has the institution and the profession of teaching here changed in all those years?

Victor Strandberg: The student body has changed, obviously, in the ethnic makeup. I think, I don’t know if I ever remember an Asian American student from the first years I was here. Certainly [it would] be very rare. And there were few black students; it was not segregated, but there were just a few black students back then. So it has gradually integrated in many ways.

It makes it a much more interesting place, really, and I think a more fertile place in an academic sense. It makes it more representative of a wider range of student experience.

Second, the ethics of the students I think has changed somewhat. The most important change, I think, has been the amount of charity work students do. It’s an enormous amount of charity work. I interview all my students, as you know, and I do ask them about extracurricular activities, and it’s almost universal that students engage in charity work. This is enormously expanded. Now part of that might be the general ethic across the whole country, it’s not just Duke, but nonetheless it does happen at Duke, or it has happened over these 50 years, and it’s a very welcome thing.

I myself did quite a lot of charity work pouring concrete, one of my skills, and sometimes Duke students and I would pour concrete for Habitat for Humanity, that kind of thing. I’m too old for it now. I’m 84 years old; they wouldn’t let me do it [now], but I did for quite a few years.

Next, I would say the change would be academic. The curriculum has changed very substantially since I first came here. When I first came here, I taught American and English literature, and there were standard courses. All students at Duke had to take two years of English or English American literature. And the curriculum was fixed, so I had a list of books I had to teach. And I didn’t mind doing that; it was good for me, and these were then considered classic books.

What we now have, it could be better in some ways, it certainly covers a lot more ground, but students no longer have a common core of literary knowledge that they used to have, and in my opinion that’s a considerable loss. Though others may say it’s worth that loss considering what’s been gained in the way of the various, you know, black studies, queer studies, women’s studies, and so on.

Duke, in terms of its physical plant, has simply exploded. It keeps broadening out to the Science Drive, for example—we never used to have a Science Drive when I started here. And the way East Campus has become a freshman campus—it was all just a women’s campus back then, and there was no interchange: no women on West Campus, no men on East Campus.

TC: Have you ever taught someone in your class who went on to be famous?

VS: As far as students who made good in the world, I’ve had something like 11 or 12 thousand students over the years, and it’s a little hard to remember everybody. And there may be students who made very well in the world indeed, but I’m not quite aware of it. But one of the students who’s done very well was a sports writer [John Feinstein, Trinity '77], he wrote a book [“A Season on the Brink”] about Indiana coach Bobby Knight’s first championship team. And his books are on sale there right now in the Duke textbook store, you walk in and you see his books. But he’s written a number of books, and he’s really hit the jackpot with them.

And there’s been others. I had a student named Ian Abrams [Trinity '77], who went to Hollywood, and he did very well. He wrote some scripts that became a television series.

TC: You’ve taught American literature the whole time you’ve been at Duke. Where did your love for that originally come from, and why have you stuck with it for so many years?

VS: Well, it developed when I was in college. And generally speaking, in college you want to do two things. You want to discover what your interests are, if you’re not sure what they are to begin with. And second, you want to see where your talent is, if you’re good at something. And if you’re fortunate, those two things will come together, what you’re interested in and what you’re good at. So I discovered in college that that was my main interest, and I was quite good at it, if I may say so. So that led to an English major, and then eventually to grad school.

I went to a working-class college—my family couldn’t afford anything more than that, and I was the first one to go to college: Clark University in Worcester, Mass., which was founded expressly for the working-class youth of Worcester county. And then I couldn’t afford to go to graduate school—had no intention to do that—but one of my professors, just one of them, he kept pushing me and pushing me and pushing me, so I hastily applied to Brown University, and that’s why I went to grad school. If I hadn’t run across the path of this professor, I never would have gone to grad school. But that’s a result of being from the working class, nobody in my family had been to college, and we didn’t really know the ropes or anything.

And then in grad school, likewise, I could pursue my interest in English and American literature, and then eventually on the job market I discovered that Duke had a high salary rating. And my wife pushed me to go after that high salary rating. We had two little girls to raise, and that would cost money. So that’s how I ended up at Duke.

TC: You’ve spent all of your sabbatical years teaching American literature abroad. Why, and what has it been like?

VS: Well, of course, I was very eager to experience other cultures. And I started with Sweden because that was the land of my ancestors. My father was an immigrant from Sweden, my mother’s people came from Sweden. So I applied and got accepted at the University of Uppsala, one of the great universities in Sweden.

And next I applied and was accepted in Belgium, at Brussels, which was a somewhat different culture. It was Catholic, for example; Sweden is Protestant. And they spoke French in Belgium, my part of Belgium. And then the next sabbatical I taught in Monheim, Germany, and the next appointment I went to Japan, a highly different culture.

Then I taught also for a month in Morocco, in Marrakesh, and that’s of course an entirely different culture too, with a call to prayer five times a day, including very early in the morning in the mosque next to my hotel, but I got so I enjoyed it. Then the last place was in the Czech lands, in a city called Olomouc. And all of these were wonderful for broadening my own experience of other cultures, and I assume that they got some benefit from my teaching of American literature over there, too.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Matthew Griffin was editor-in-chief of The Chronicle's 116th volume.