It was a gloomy day in March 2014. Thousands of students were walking around campus, going to and from their classes, minding their own business.

What they might not have known is that on this particular day, Duke researchers were recording them and putting their likenesses into a data set. This data set would be placed on a public website, and it would be downloaded by academics, security contractors and military researchers around the globe.

Researchers employed the surveillance footage data to test and improve facial recognition technology, which has been used primarily for public or private security purposes. The data has been linked to the Chinese government’s surveillance of ethnic minorities.

The data set and the project’s Duke website were taken down in April, after Microsoft came under fire for its facial recognition database that had more than 10 million images of roughly 100,000 people. The company's database was exposed in a Financial Times investigation, in which the data set from Duke was also mentioned as "one of the most popular pedestrian recognition training sets.”

Microsoft has since pulled its data set, and Stanford University also removed one of its public data sets.

The takedown of the website from Duke came after media reports spurred an investigation by the Institutional Review Board, wrote Michael Schoenfeld, vice president for public affairs and government relations, in an email to The Chronicle.

Schoenfeld explained that the investigation revealed that the Duke study’s data was “neither collected nor made available to the public consistent with the terms of the study that had been approved by the Institutional Review Board.”

The IRB—which reviews all studies involving human subjects—approved a study that would take place in a “defined indoor space” and create a data set that would be accessible only upon researchers’ request. Instead, the researchers performed the study outdoors and placed the data on a public website, he wrote.

“As a result of this significant deviation from the approved protocol, the public website was taken down on April 25, 2019, and there are no plans to reopen it,” Schoenfeld added.

The data set was especially popular in China, where it was used by private companies and military academies to test their own facial recognition technology. China has used artificial intelligence to monitor and oppress minority ethnic groups, most notably the Muslim Uyghur population.

“We have no way of knowing how it was used by those who may have accessed it while it was live,” Schoenfeld wrote.

In September 2016, researchers from Duke and the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia in Modena, Italy, published a paper written to help accelerate progress with developing multi-target, multi-camera (MTMC) tracking systems.

“As MTMC methods solve larger and larger problems,” the paper reads, “it becomes increasingly important (i) to agree on straightforward performance measures that consistently report bottom-line tracker performance, both within and across cameras; (ii) to develop realistically large benchmark data sets for performance evaluation; and (iii) to compare system performance end-to-end.”

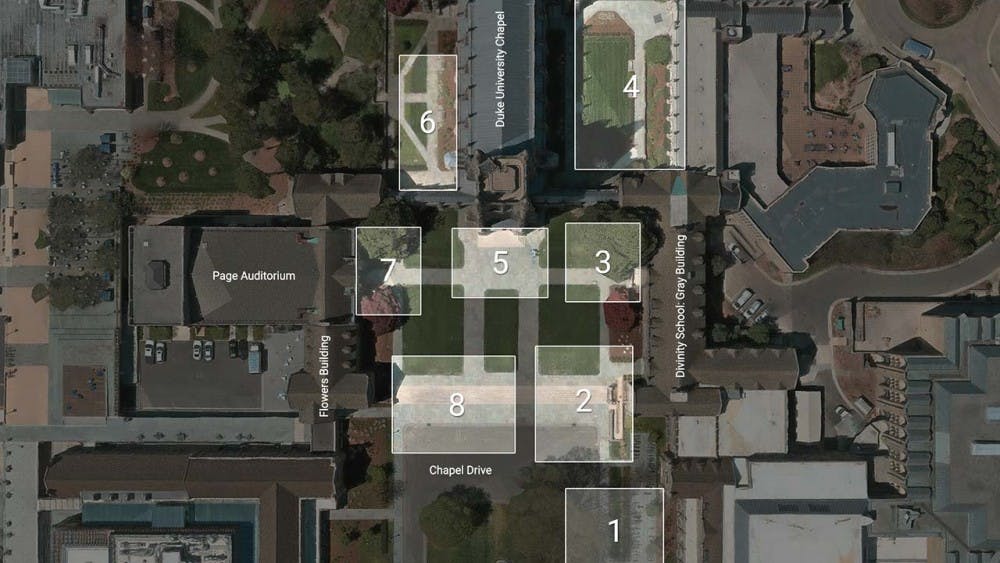

In the paper, the researchers presented a data set they had compiled, consisting of more than 2 million image frames of around 2,000 students from eight cameras placed around campus. The data set was known as the DukeMTMC. The study was funded by the U.S. Army Research Office and the National Science Foundation.

The 85 minutes of video from each camera was captured on one day in March 2014, when researchers knew students would be transitioning between classes.

Ergys Ristani, Graduate School ‘18 and a co-author of the original paper, told the Financial Times that posters were set up around the surveilled area to warn people, and no one asked to be excluded from the data set. It’s unclear whether every passerby saw the posters or understood the ramifications.

Carlo Tomasi—Iris Einheuser professor of computer science at Duke, Ristani’s supervisor and an author of the original paper—declined to comment on the data set, but wrote a letter to the editor offering clarification and an apology.

"I have never worked on facial recognition. We recorded the data to research methods to analyze the motion of objects in video, whether they are people, cars, fish or other," he wrote. "I take full responsibility for my mistakes, and I apologize to all people who were recorded and to Duke for their consequences."

Although the site has been taken down, between 2016 and 2019, researchers from the United States, China, Australia, the United Kingdom and other countries downloaded DukeMTMC in order to test their person re-identification software—a technology designed to match images of pedestrians across different cameras and camera angles. It’s challenging due to varied body positions and obstructions that mask or shadow faces.

Chinese researchers used DukeMTMC more than anyone else, with 143 verified citations, or 47.8% of worldwide verified citations, according to a Megapixels report on the data set. Megapixels is a research project by researcher Adam Harvey and technologist Jules LaPlace that studies facial recognition databases and biometric surveillance. The United States was second with 57.

An April article in the New York Times discussed how China is using widespread surveillance and artificial intelligence to racially track and profile the Uyghur ethnic minority. The article listed Yitu, Megvii, SenseTime, Hikvision and CloudWalk as five Chinese companies that have provided police with the necessary facial recognition software.

The Megapixels report found that Megvii, SenseTime, Hikvision and CloudWalk have all used DukeMTMC or data sets extended from it to test their research on person re-identification.

Additionally, two military academies in China—National University of Defense Technology and Army Engineering University of People’s Liberation Army—that are under the control of their top military body, have also tested software on the DukeMTMC data set.

“Over 2,000 students and visitors who happened to be walking to class in 2014 will forever remain in all downloaded copies of the Duke MTMC data set and all its extensions,” Harvey and LaPlace wrote, “contributing to a global supply chain of data that powers governmental and commercial expansion of biometric surveillance technologies.”

Nathan Luzum and Isabelle Doan contributed reporting.

Editor's Note: This article was updated Thursday at 6:45 p.m. with Tomasi's comments from his letter to the editor.

The Chronicle is not finished investigating the DukeMTMC data set. We would appreciate hearing what you know, think or wonder about it. Please use the form below to leave your comments and questions.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Jake Satisky is a Trinity senior and the digital strategy director for Volume 116. He was the Editor-in-Chief for Volume 115 of The Chronicle.