Editor's Note: This story is part four of a four-part oral history of the 1969 Allen Building Takeover. Read part one here, part two here and part three here.

On February 13, 1969, approximately 60 Duke students occupied the first floor of the Allen Building to protest the University’s failure to meet the needs of black students. Their demands included the creation of a Department of “Afro-American” Studies, increased enrollment and financial support for black students and a black student union. Protesters remained in the building until after 5:00 p.m, when their exit ignited a clash on the main quad in front of Perkins Library between students gathered outside and police.

No two protesters experienced that day—or the months and years that followed—the same way. Over time, the protest has been absorbed into Duke’s history—there was an official commemoration on the 50th anniversary. Beyond public recognition, however, the memories and lessons of that day remain deeply personal for many of the protesters, whose lives were changed by the act of resistance, the risk of violent force and potential retaliation from the university.

From original interviews, testimony at panel events and archival material, we have compiled personal stories of the 1969 Allen Building Takeover—in the words of those who were there. Some statements have been edited for length and clarity.

'Strong sense of purpose': Life after the Takeover

The Allen Building Takeover was not just a pivotal moment in Duke history but also a significant event in each of the protesters’ lives.

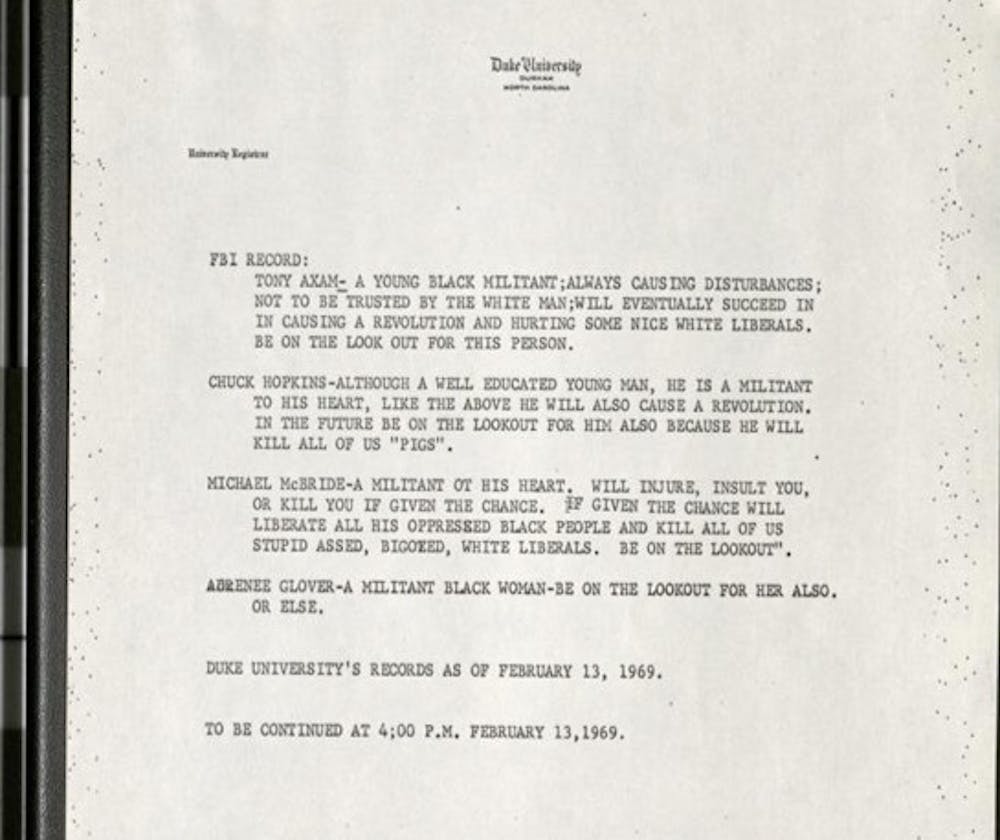

Michael McBride (Trinity ‘71, former chairman of Afro-American Society): I’m not sure when the FBI started watching me, but they did. I found out when I got ready to leave Durham. I was working at a post office... The FBI came by the post office... [An FBI agent] said to me, “I heard you were leaving town soon, so I rushed right down here.”

“How did you know I was leaving town soon?”

He said, “Well, I guess I picked it up somewhere.” He told me, you know, “Well, you know, we watched all you guys, we kept files on you.”

I said, “Why?”

And he said, “We didn't know where your loyalties were."

And until that happened I thought we were all flattering ourselves, you know, saying the FBI was keeping files on us but we weren’t, they were... They kept files on a lot of black students at white colleges. Fortunately, that hasn't affected me afterward. It just shows you how we were viewed by the government.

Catherine LeBlanc (Trinity ‘71): I was sort of bathed in the commitment to wanting to make a difference in my community and so from that point on every job I took—whether it was corporate or not—involved me in some way with the black community. And after being in corporate for about 15 years, I did not have the same sense of purpose and fulfillment with my jobs in corporate. And so I actually left corporate.

And I remember a friend of mine saying to me, “You know, you [have a Master of Business Administration from Harvard]. Why are you going to work for the Atlanta public schools?” He said, “You are an anachronism from the ‘60s.”

At that time, I guess I was. This was in the ‘80s. I left because of the level of commitment that had really gotten galvanized out of the experience, 1969, and at a certain point it just would not be silent, that desire to want to do something that would have a deeper impact on people of color every day... Since then I have worked in the non-profit sector. I have worked in the public sector. And I just have a very strong sense of purpose about my life and what I do.

McBride: [The protest] was important to us, and it's been validated through the years. One of my personal physicians some years ago said, "I had a daughter who came to Duke," and he said, "I want to thank y'all for what you did."

Fifty years later

In February of 2019, many of the original Allen Building protesters and their families met for a weekend-long commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the takeover. From the Washington Duke Inn to the Nasher Museum of Art, the event celebrated the Takeover and its participants—a sharp contrast to how the students were treated 50 years earlier. The events included remarks from Mark Anthony Neal, the chair of Duke’s African and African American studies department, members of Duke’s senior leadership team, testimony from the original protesters and reflections from current students.

Valerie Ashby (Dean of Trinity College of Arts and Sciences), in an address to Allen Building protesters: I go into my office, which is 104 Allen Building, which is right outside where you did your work and I am not confused. I am not confused about how I am able to walk into that office every day. I owe you a huge debt of gratitude. You began a movement in 1969, the benefits of which my colleagues are reaping every day. Our job is to make you proud.

Mark Anthony Neal, in an address to Allen Building protesters: I speak with you... as the James B. Duke professor and chair of the nationally and internationally renowned department of African and African American studies in large part because of the vision and bravery of those students.

President Vincent Price, in an address to the Allen Building protesters: The occupation of the Allen Building was one of the most pivotal moments in our university’s history, a moment that would not have been possible without your courage and conviction and your willingness to stand up for what was right. In the actions that you took, you forever shifted our sails toward the prevailing winds of justice and equality.

In the panels and our interviews, the protesters had varying opinions on being honored for actions that were condemned 50 years ago.

Vaughn C. Glapion (Trinity ‘71): If it weren’t for [Catherine] LeBlanc, Bertie Howard [Trinity ‘69] and other people part of the steering committee, I don’t know if this weekend would have happened... When I walk across campus, I don’t feel any more welcome now then back then. When I look around at everyone walking around campus, I don’t see any more flavor.

Janice Williams (Trinity ‘72): You’re still invisible when you walk on Duke’s campus... I don’t want to contribute all of that necessarily to racism. I think some of that has to also do with the vast mix. You’re not in a microcosm of the Southeast where we’re taught to speak or you get in trouble if you don’t say hey to everybody... It’s almost the same feeling as when you go to New York.

Glapion: I think the Washington Duke Inn was a great place to have the event. All I’m saying is when I went in there, I had a feeling of the old, entrenched plantation system... That Washington Duke Inn kind of reinforced what Duke really is... how entrenched racism is in American life.

McBride: I didn't realize how ambivalent I was about Duke until about... Do you remember the Duke lacrosse thing? Not long after that happened, I was part of a focus group in the Atlanta area that Duke had. It was all black students in the focus group. I was the oldest one there, and the young alumni were very positive about Duke, about the experience they had.

I remember one young woman saying she could not understand how anyone who finished Duke could not support the school because she had a great experience and she would always support it so that others could have the kind of experience that she had. She convinced me to start contributing to the alumni fund, but you could tell how young the alumni were based on how positive their experience was, because mine was the most negative, and then the next oldest person was a little less negative, and then, you know, they became positive.

LeBlanc: We were just very pleased at this point that the University recognizes that something good took place and we really did make a contribution and whenever you get affirmed, I don’t care how long it takes, it makes a difference... . Whenever you make a choice to take a stand in what you believe, you just have to prepared for the consequences, whatever form those consequences might take.

Original Allen Building takeover participants gather for a group portrait at Duke Gardens. Source: Duke University Communications

Williams: I noticed this at the panel. All the people who got up to speak, other than us, got up to say, “Thank you so much, I wouldn’t have had my job if it hadn’t been for you.” But you didn’t see one white person say, “Thank you so much for enriching my life and enabling me to have to work for or alongside these people who are here.” I think that would have made a difference in your perspective on whether Duke has really made it.

McBride: I think Duke had to be pushed. All institutions have to be pushed, even so-called “liberal institutions.” Institutions forget their missions, and they start to exist solely to exist. They just want to perpetuate themselves. They just want to live, it’s almost like an organism...

I could’ve left and gone to a black school, but we couldn’t do that. So we decided to fight. Freedom riders made sacrifices, people lost their lives. So I could fail some classes. I didn’t lose my life... I still had, and I’m still having a good life, is all I’ve got to say. I didn’t see that I had a choice. I don’t think that many of us felt that we had a choice. That’s what black people had to do. You had to fight. You had to win some battles, you lose some battles, but the struggle goes on.

Authors’ Note

As Duke commemorated the 50th Anniversary of the Allen Building Takeover in February 2019, many of the original protesters gathered at Duke, creating a unique opportunity for journalists and documentarians to capture their stories. This oral history pulls heavily from a panel discussion that took place at the 50th Anniversary event. The panel featured Catherine LeBlanc, Michael LeBlanc, Janice Williams, Chuck Thompson, Michael McBride and Charles Becton. We drew from speeches made over the course of the weekend by Catherine LeBlanc, Dean Valerie Ashby, Professor Mark Anthony Neal and President Vincent Price.

We conducted in-person interviews with Reed Kramer, Mark Pinsky, Michael LeBlanc and Bertie Howard, as well as phone interviews with Janice Williams and Michael McBride. We also facilitated a conversation between Vaughn Glapion, Janice Williams and Bertie Howard. We had the benefit of 50 years of archival material with which to further tell this story. We spoke with University Archivist Val Gillespie and drew from the President Douglas Knight papers, previous editions of The Chronicle, the Allen Building Takeover Oral History Collection, the interviews of Bill Turner and Janice Williams conducted by Don Yanella in 1985 and the exhibition of the Allen Building Takeover.

It is our hope that current and future Duke students will see the Allen Building Takeover as the protesters did—as a complex event, as significant to understanding the challenges of minorities today and as an incredible risk taken by students for the future of the University.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.