Talking in hushed voices, a committee gathers around a table in a conference room. At a nearby airport, an airplane lands on the tarmac. One of the passengers exits the plane and is whisked into the conference room, questioned by the committee for an hour and then rushed out so as not to be seen by the next arrival. Shortly after, the process is repeated with someone else.

It’s not a scene from the next James Bond movie—it’s a key step in the process for those vying to become a high-level Duke administrator.

The University’s administrative search process is complex, involving search firms, search committees, applications and multiple rounds of interviews. Throughout the many stages of the process, the search committee winnows down the list of candidates and submits it to a top administrator or the Board of Trustees, one of whom makes the final decision.

“We do this often, and we have a number of senior positions,” said Michael Schoenfeld, vice president for public affairs and government relations. “They demand a very high level of review and deliberation.”

The Chronicle spoke with several individuals who have participated in Duke’s administrative searches to tease apart what it takes to become one of the University’s leaders.

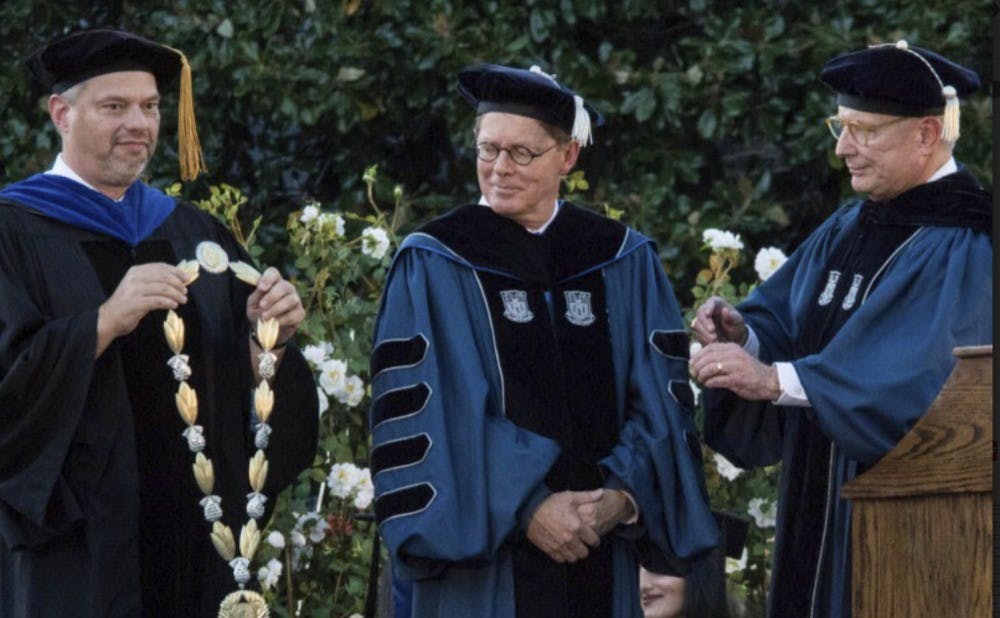

The searches discussed in this article brought Larry Moneta—outgoing vice president for student affairs—to Duke in 2001 and his replacement, Mary Pat McMahon—incoming vice provost/vice president for campus life—to the University in 2019. They also led to the hiring of Vincent Price as Duke’s 10th president in 2016 and Schoenfeld’s appointment in 2008.

‘Big picture sense’: The beginnings of a search

At the heart of every administrative search is a search committee, typically consisting of 10 to 20 people drawn from Duke’s supply of Trustees, deans, faculty, administrators and students. Formed by a high-level administrator such as the president or provost, the search committee is charged with evaluating applicants and submitting a report recommending candidates for the position.

Jack Bovender, Trinity ‘67 and Graduate School ‘69, served as the chair of the search committee tasked with selecting former President Richard Brodhead’s successor in 2016.

He explained that the composition of the committee is an important factor in the search process. For example, when the presidential search committee was being formed, he requested that each dean nominate five faculty members for consideration to become a part of the group.

“It was a process that took in a lot of input from a lot of different sources,” said Bovender, who currently serves as chair of Duke’s Board of Trustees. “[The committee members] came together very, very well, and it became a collegial group.”

Once the committee is formed, it’s time for the members to learn more about the administrative position in question.

Professor of Biology Steve Nowicki has served on several search committees and was co-chair of the committee that brought Moneta to Duke in 2001. Nowicki recalled that searches began by getting a “big picture sense” of important qualities that committee members should be looking for in prospective candidates.

“You start by meeting with whichever senior administrator the person being hired will report to and get what you might call a charge to the committee,” said Nowicki, who also served as Duke’s dean and vice provost for undergraduate education from 2007 to 2018. “Once the committee is assembled, a typical first meeting is to have somebody come in and say ‘These are the key things to keep in mind—these are the priorities I’m interested in.’”

Emily Bernhardt, Jerry G. and Patricia Crawford Hubbard professor in the biology department, chaired the search committee that found McMahon in Spring 2019. She said that her tenure as chair began with her meeting with employees in the Student Affairs department to understand the ins and outs of the job that Moneta’s successor would inherit.

At this point, committee members also begin thinking about potential candidates. Nowicki and Bernhardt said they called faculty members at other institutions who might be able to point them in the right direction. Sometimes the same name would keep popping up during these calls, which would place the candidate in question on the search committee’s radar.

Bovender recalled putting out a call to faculty, alumni and students to nominate candidates to fill Duke’s presidential vacancy, though many of these suggestions were politicians and business leaders whom the search committee did not seriously consider.

“We made the decision very early on that we were going to get an academic—someone who could easily be a part of the faculty at Duke but somebody who has leadership experience at the academy so that they understood the complexities,” Bovender said.

A subset of the search committee—dubbed the “travel squad”—also flew around the country on Bovender’s personal airplane to interview top administrators and candidates. These trips took them across America, from Harvard to Stanford to the University of Chicago, and helped them establish an initial roster of prospects.

‘They have the expertise’: A search firm enters the picture

Calling colleagues at other universities will add a few names to the list, Nowicki explained, but what search committees really need is someone with an intimate knowledge of the university administrative landscape across the country—and that’s where the search firm comes in.

“If you’re searching for a president or a provost or even a dean of a school, you’re always going to engage a search firm,” Nowicki said. “They’re the people who are the professionals who are able to use their connections to get out nationally and put the word out, identify candidates that locally you may just not know about and help bring the whole thing together.”

One such firm is Isaacson, Miller, which the University tapped to assist with the searches that selected Price and McMahon.

In an email to The Chronicle, Mary Connolly, director of business development for the firm, declined to comment on the firm’s role in the search process.

Bovender said that he requested that John Isaacson—the founder and namesake of the firm—oversee the presidential search. Isaacson agreed and set the wheels in motion.

“He and his people helped us put together a synopsis of who we are and what we are at Duke,” Bovender explained. “They did that by interviewing significant numbers of people—deans, members of the faculty, members of the administration, key athletic coaches and so forth.”

Once the firm has a solid grasp of what the University is looking for, it will begin to curate a list of potential fits for the position and solicit applications.

The number of applicants and serious contenders can vary from search to search. Bernhardt recalled that during the search for Moneta’s successor, Isaacson, Miller brought the committee 35 applications from serious contenders. Nowicki said that, in his experience, the starting point might be anywhere from several dozen applications to more than 100.

He estimated that slightly more than half of the candidates on the search committee’s preliminary list end up submitting applications—but that proportion can differ depending on the position.

Nowicki explained that searches tend to focus on two types of candidates. The candidate could be the “No. 1 at a No. 2 institution”—someone who holds a top position at a university that is perceived to be lower caliber than Duke—or the “No. 2 at a No. 1 institution,” someone at a mid-level position at another elite college.

One red flag that can come up during a search, he added, is when candidates apply for the job before the search committee or search firm has sought them out. He explained that candidates often have to be “courted,” and those who would make effective university administrators should not be desperately job hunting.

‘What you’re typically looking for’: Picking the right candidate

Once the applications have been collected, the search committee needs to winnow the field to a smaller number of semifinalists—usually between 10 and 20.

Nowicki explained that there are general attributes important for candidates in any search, as well as more specific qualities for which the committee might be screening in a particular scenario.

Good candidates ought to be “sharp”—which is different from book-smart, he added—have an open mind, articulate a vision for the University and be easy to maintain a conversation with. Another important attribute is the ability to speak one’s mind, a quality he said that Moneta showed in 2001.

“What you’re typically looking for is some combination of a person who has really excelled where they are but has a reason to want to move to a new place,” Nowicki explained.

Bernhardt added that the committee looked for candidates who were prepared to deal “with the inevitable controversial issues of free speech and hate speech.” Moneta has come under fire in the past two years for his handling of speech incidents on campus.

“What we were looking for in the search are people who could handle a really complex business organization, but also have incredible people skills and a real passion for taking care of students—and I mean all students,” Bernhardt said of the search for Moneta’s replacement.

With these principles in mind, Nowicki explained that search committees choose semifinalists using the written materials provided by the candidates, such as CVs and cover letters. This first round of vetting can take a different form depending on the search.

Bovender said that after all applications were received, the presidential search committee conducted a forced ranking in which committee members were required to rank each applicant.

Seven names clustered toward the top when the rankings were aggregated. These became the candidates who would advance.

Then, it’s time for the airport interview.

Although not every search features one—Nowicki recalled that the search that found Moneta relied on phone interviews instead—the airport interview is an important opportunity for a subset of the search committee to meet the candidates face-to-face.

The interviews typically take place in a conference room near a major airport over several days. Nowicki stressed that the offsite discussions are meant to maintain confidentiality—even the semifinalists don’t know their competition.

“The trick is to have these things sort of spread out in space and time explicitly so that the candidates don’t bump into each other,” he said. “Anybody applying for the same job is very likely to know some of the other people.”

The “cloak-and-dagger” nature of the airport interview is not intended to make the search process more secretive, Nowicki explained, but rather to protect the confidentiality of the interviewees.

“A lot of people complain about how it should be more transparent, but not really, because the best people are already in good jobs where they may want to stay,” Nowicki said. “So if it becomes public that they’re looking for a job, it becomes difficult.”

The interview is a “two-way street,” he added, in that the candidates are also evaluating the committee and deciding whether the institution would be a good fit during their interview.

Bernhardt said there were nine semifinalists who participated in the airport interviews for Moneta’s replacement at an undisclosed location, and the semifinalist interviews for the presidential position were held with seven candidates in New York City, Bovender revealed.

Search committees typically narrow the field to three or four finalists after the airport interviews. For the 2016 presidential search, Bovender said this again took place via forced ranking.

These finalists are invited to campus, where they will undergo further evaluation and meet with a variety of administrators and rank-and-file employees. This is also when the search committee calls references for the candidates, Nowicki said.

The search for Moneta’s successor brought four finalists to campus, and three finalists visited Duke in the running to become Brodhead’s replacement—there was originally a fourth, Bovender explained, but she bowed out of the process to pursue another presidential search that was “a little bit ahead” of Duke’s.

This stage of the search is as confidential as the last. Schoenfeld was hired in 2008 and said that, to this day, he does not know who the other finalists for the job were.

Finally, the search committee meets with the administrator or administrators to whom the chosen candidate will report and submits a final recommendation, which may feature a ranked or unranked list of candidates. In the case of the search for Moneta’s successor, the report featured an unranked list of four candidates, Bernhardt said.

For the presidential search, Bovender said that Price was the only name sent forward in the report.

“After a discussion and a vote, it was unanimous for [Price],” he said.

Once the report is submitted, the hiring decision rests with the supervising administrators. In 2016, the Board of Trustees took up the committee’s recommendation and agreed to tap Price as the University’s 10th president. For the search that brought in McMahon to replace Moneta, Bernhardt explained that Provost Sally Kornbluth and Price made the final call.

‘Find people who are better than you’: Evaluating internal and external candidates

All four searches discussed in this article resulted in hiring candidates from universities other than Duke: Moneta and Price from the University of Pennsylvania, McMahon from Tufts and Schoenfeld from Vanderbilt.

Nowicki explained that most searches don’t explicitly ban internal candidates from applying, but that the search committee has a general idea about the quality of prospective applicants already at Duke.

In the search for Moneta in 2001, Nowicki remarked that no internal candidate “[rose] to the quality” that they were looking for, except Sue Wasiolek—dean of students and associate vice president for student affairs—who was named a finalist for that search.

Certain roles have recently trended more toward internal or external candidates, Nowicki explained. Price and his two predecessors as president were external hires, whereas Kornbluth and former Provost Peter Lange served as Duke faculty members before their hiring.

Schoenfeld acknowledged that selections “may have a certain pattern” but explained that searches often include both internal and external candidates.

One reason that Duke tends to hire external candidates to certain positions, Nowicki explained, is that the University stands to gain from recruiting talent from other universities.

“Duke has become a premier institution in the last 40 years or so, and often you do that by saying ‘We have to bring in outside talent, we have to keep recruiting people who are better than us,’” he said. “It’s OK to find people who are better than you. You always want to do that as an institution.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.