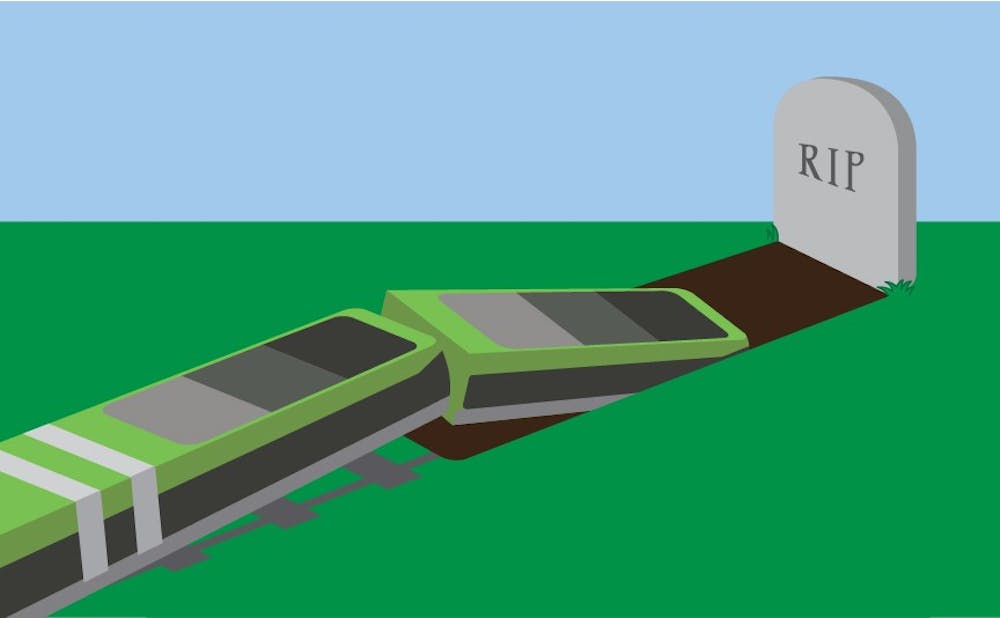

Congressman David Price was “profoundly disappointed” when the light rail died.

Price expressed his frustration at the failure of a project that he said “voters, businesses and government leaders overwhelmingly supported” in a news release March 27, the day GoTriangle ended the light rail project. Price has represented a portion of North Carolina’s Research Triangle in Congress every year except two since 1987, and he was a professor at the Sanford School of Public Policy prior to his tenure in the House of Representatives.

Price is the chairman of the House Subcommittee on Transportation, and Housing and Urban Development and Related Agencies, which had the power to give approximately $1.23 billion to Durham and Orange Counties to help fund a light rail spanning from Durham to Chapel Hill.

The Durham-Orange County Light Rail Transit project (DOLRT) faced a number of hurdles in its lifetime. GoTriangle—the public transit authority in charge of the project—was working against a tight deadline, the North Carolina Railroad hadn’t agreed to lease parts of its railroad corridor and costs were skyrocketing. And there was Duke, which was reluctant to sign a cooperation agreement and give up its land near the medical center by Erwin Road for the project.

Then the University sent a letter to GoTriangle Feb. 27 that all but killed the light rail.

"Notwithstanding these many good faith efforts, it has unfortunately not been possible to complete the extensive and detailed due diligence, by the deadlines imposed by the federal and state governments, that is required to satisfy Duke University's legal, ethical and fiduciary responsibilities to ensure the safety of patients, the integrity of research and continuity of our operations and activities," President Vincent Price wrote in the Feb. 27 letter to GoTriangle detailing why Duke would not sign the cooperation agreement.

The backlash was swift, with IndyWeek and the New York Times running pieces that pointed fingers at Duke for the light rail’s demise. But the University defended its choice, pointing to potential dangers to the medical center.

So who is to blame for derailing the light rail? If you ask Duke, the administration was clear for 20 years that building tracks 100 feet from the medical center was problematic, and GoTriangle wouldn’t listen. GoTriangle would push back and argue that Duke has been an inconsistent, opaque negotiator that did not make its concerns clear until it was too late.

But the University was just one of many entities involved in the pathway to build a light rail connecting Durham to Chapel Hill.

“The issue is, it's really fun and easy to blame Duke,” Executive Vice President Tallman Trask told The Chronicle in late March. “We're the least of [GoTriangle’s] problems. They're hundreds and hundreds of millions of dollars over budget, even the inflated budget.”

Bill Bell, former Durham mayor and IBM senior engineer, described the DOLRT as an AND gate on a computer chip—every input had to come true for the output to be true. GoTriangle had secured cooperation from many of its partners, but in addition to Duke, it still needed Federal Transit Administration funding, state funding, local and private funding and the North Carolina Railroad Company (NCRR)/Norfolk Southern’s cooperation. If everything didn’t break the right way, there would be no light rail.

Transit is not a new problem

The Triangle—the region anchored by Raleigh, Durham and Chapel Hill—has been wrestling with the idea of a light rail for more than 20 years to deal with its rapid growth. The area is one of the fastest growing in the country, featuring a business hotbed in the Research Triangle Park and three major research universities.

For example, the Raleigh-Cary metropolitan area saw an 18.1% surge in population from 2010 to 2017, and traffic planners are preparing for another half million people within the next decade.

The fight to reduce traffic and connect people in a rapidly growing region has been arduous yet persistent. In 1989, North Carolina’s General Assembly created the Triangle Transit Authority to serve as the regional public transit authority for Wake, Orange and Durham counties.

In the late 1990s, the TTA devised plans for a diesel rail line from Raleigh to Durham. The designs had an elevated stop by Duke Hospital’s main entrance and a track continuing down Erwin Road, Duke’s medical corridor. The University disapproved of the plans, however, citing Erwin as its main problem. Trask said constructability and noise from diesel were Duke’s two main concerns, in addition to fears that the rail line would disrupt hospital operations.

Securing federal funding from the Federal Transit Administration proved to be a challenge as well. Facing rising costs, a change in the federal cost-benefit formula and weak FTA interest, TTA scrapped the project officially in 2007.

From 2008-2009, the rebranded Triangle Transit worked with local governments to develop a regional plan for transit, including buses, light rail and commuter rail. The General Assembly passed a law allowing Triangle counties to put a half-cent sales tax for transit on the ballot, which passed in Durham and Orange Counties in 2011 and 2012, respectively. The next few years saw Triangle Transit working with the FTA to design a Durham-Orange electric light rail route.

‘We didn’t have forever’: Wrestling with the state

Building the light rails is not cheap. To complete the project, it required state and the federal government assistance.

The FTA committed about $1.25 billion to the DOLRT project, provided GoTriangle could cover the rest of the $2.7 billion cost. When Charlotte, N.C., wanted to build its Lynx Blue Line, it secured 50% of funding from the FTA, and approximately 25% each from North Carolina and the local government. Thus, Durham County Commissioner Ellen Reckhow explained that GoTriangle believed it would be able to get half of the remaining money from the state.

The North Carolina General Assembly had other ideas.

In 2015, the legislature reduced how much it would contribute to light rail projects to $500,000. After several years of lobbying and back-and-forths with the Republican-led General Assembly, GoTriangle finally got the state to commit more money in the summer of 2018. The state would offer a maximum of $190 million, or around 7.7% of the total estimated project cost.

The state said that all local funding must be in place by April 30, 2019 and federal funding must be ready by Nov. 30. The time constraints were “unprecedented,” Reckhow said.

Wib Gulley, Trinity ‘70 and general counsel for GoTriangle from 2004-2015, said he believed the General Assembly had partisan motivations.

"This is the Republican-led state legislature,” he said. “I think it's important to note that because, for whatever reasons, the Republican leadership of the General Assembly has been hostile to [DOLRT]. I think the fact that these two counties are the most Democratic in the state and [the legislature is] Republican is one thing."

North Carolina State Senator Floyd McKissick Jr. told the Durham Herald-Sun that it took more than a week of work to reach a consensus with the General Assembly. He said legislators are more interested in seeing road infrastructure projects rather than light rail.

“First, you have people who are skeptical of mass transit, don’t believe the light rail system is needed and are afraid that it would soak up more money than is currently allocated for it,” McKissick told the Herald-Sun.

Gulley added that he didn’t think North Carolina leaders understood the need for light rail in sprawling metropolitan regions such as the Triangle. As a result, GoTriangle suddenly faced a wide gap in fundraising it had to make up in a short time frame. GoTransit Partners—the fundraising arm of GoTriangle—was having trouble raising private money because the project’s success seemed unlikely.

“If we had forever to solve the problem, we could've solved the problems,” Bell—a GoTransit board member—said. “But we didn't have forever.”

A tunnel to nowhere

Gulley and Reckhow remained confident that had Duke signed the cooperative agreement, DOLRT’s future would still be bright. However, Reckhow did say that it wouldn’t have necessarily been smooth riding.

"We, in good faith, thought through the end of February that we could have proceeded if we had gotten the cooperative agreement from Duke,” she said. “But amazingly, just within 8 to 10 days after Feb. 28, we got some news that substantially hurt us, and then the project cost increases that came out of the risk assessment were $237 million.”

The additional cost estimates were a result of needing to build a tunnel in downtown Durham to accommodate the light rail without stalling downtown businesses.

NCRR—which operates the rail corridor GoTriangle wanted to build its light rail on—and its main operating partner, Norfolk Southern, were two other partners DOLRT needed cooperation agreements from in order to proceed.

They were concerned with the light rail’s potential alignment in downtown Durham, especially at the Blackwell Street railroad intersection. As a result, GoTriangle proposed closing Blackwell Street and adding a pedestrian bridge so people could cross it.

That proposal did not go over well. Duke, the Durham Bulls and businesses in the American Tobacco Campus complained that closing Blackwell Street would choke them off from the rest of downtown Durham. Two board members from GoTransit resigned in protest.

Therefore, GoTriangle told the FTA in December it would build a tunnel underneath downtown Durham for the light rail. The agency had five months until the April deadline and 11 months until the November deadline. GoTriangle asked the FTA if there would need to be another environmental review for the downtown tunnel.

And then the federal government shut down for 35 days.

GoTriangle didn’t hear back from the FTA until the first weekend of March, after Duke had sent its letter announcing the refusal to cooperate. The same day Duke said no, NCRR sent a letter stating that it would not sign on until the downtown plans were more complete.

To make matters worse, the FTA said the agency did need to conduct an environmental review for downtown, and it estimated the new plan would add $237 million to the project—not including the 10% fund reserve the agency had to have in case they went over budget downtown. Having to do the environmental review meant that the agency probably wouldn’t have submitted its FTA grant application on time to meet the state’s deadline.

No winners, all losers

Bell compared the DOLRT project to a “a circle of dominoes. When one falls, the rest come down.” To Bell, Duke was that first domino to fall—taking down the entire project with it—but it wasn’t the sole factor that could have killed the light rail.

So where does public transit go from here? In his news release, Price said he was “committed to working with local leaders” to move past the light rail’s setback and address the region’s transit needs.

“Doing so will require all stakeholders to put the long-term interests of our communities ahead of the narrow concerns that doomed this project,” he said in the release.

Reckhow also said she had not given up on mass transportation, and that GoTriangle and Durham County are devoted to finding a solution to the region’s transit woes.

“We will be looking at whether there are aspects of the light rail project we can repurpose, ways to use the corridor we know so well with different technology, are there ways to do a blended situation,” she said. “We'll be looking at a variety of options.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Jake Satisky is a Trinity senior and the digital strategy director for Volume 116. He was the Editor-in-Chief for Volume 115 of The Chronicle.