Everyone knows the Duke Lemur Center, home to the largest collection of lemurs outside of Madagascar.

But not everyone knows the story of who founded it—John Buettner-Janusch.

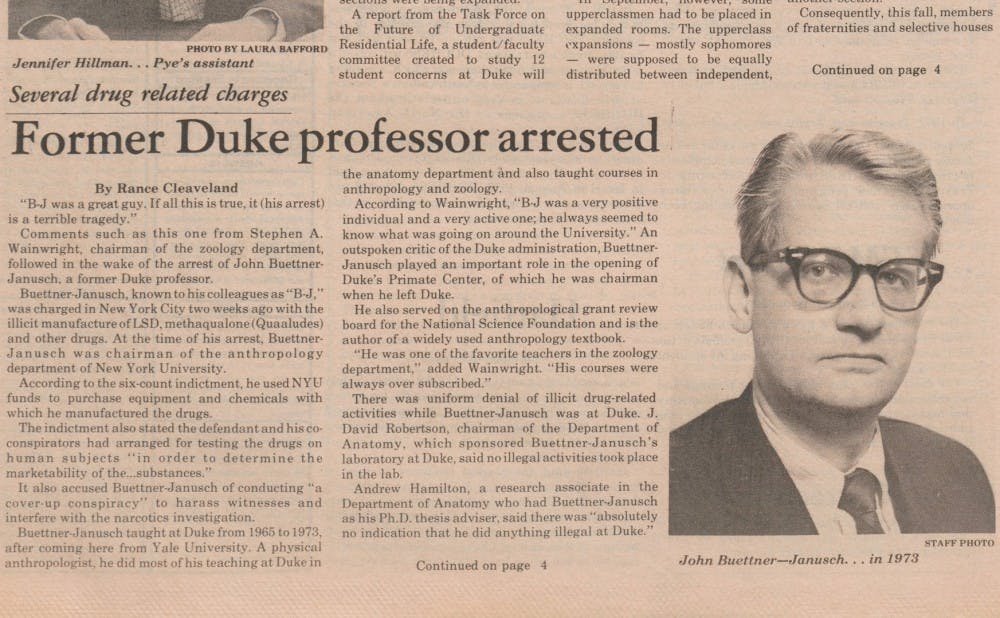

Buettner-Janusch, known as B-J, came to Duke in 1965 and founded the DLC in 1966 as a non-invasive research facility. After leaving Duke in 1973, Buettner-Janusch was found guilty in 1980 of manufacturing LSD and methaqualone in his Manhattan laboratory. Once released, he sent the federal judge who convicted him and others poisoned chocolates—for which he received a 20-year sentence—and died in prison at 67 years old.

Since Buettner-Janusch's time at Duke, the Duke Lemur Center has transformed into a world-class research center.

“The DLC wouldn’t be here today were it not for Buettner-Janusch," said Sara Clark, director of communications for the DLC. "B-J’s contributions to the Duke Lemur Center were huge: the roughly 90 animals that founded the DLC colony were B-J’s, and they moved with him from Yale to Duke. He was one of the first Americans to study lemurs, and he’s inspired generations of lemur researchers since–including all of us here at Duke.”

'Too arrogant to keep his foot out of his mouth'

During World War II, Buettner-Janusch was jailed as a "conscientious objector." Soon after, he received his bachelor's and master's degrees from the University of Chicago. In 1957, Buettner-Janusch received his doctorate from the University of Michigan.

In 1959, Buettner-Janusch began teaching in Yale University's anthropology department. There, he researched the genetic makeup of the Kenyan baboon and was a pioneer in using a method of electrophoresis.

After seven years in New Haven, Conn., Buettner-Janusch's desire to start his own program and to expand his fledgling primate collection propelled him south to Durham. During his time at Duke, Buettner-Janusch led the DLC. He also published the first of his two textbooks, "Origins of Man," alongside his wife Vina Mallowitz Buettner-Janusch.

While at Duke, Buettner-Janusch encountered Peter Klopfer, now professor emeritus of biology. Although Buettner-Janusch took more interest in the physiological and breeding aspects of primates and Klopfer the behavioral side, the two became close associates due to their passion to improve Duke’s resources.

“We decided together that we would establish a center for primate research,” Klopfer said.

Klopfer remembers Buettner-Janusch as “a brilliant scientist who was also egoistic,” and colleagues described him as "brilliant" in his New York Times obituary.

Indeed, Buettner-Janusch was offended when New York University pitched him a salary that Duke would not match—he left Durham soon after. Still, Klopfer believes that Buettner-Janusch ultimately regretted his prioritizing money over the staff at the DLC.

“He was too arrogant to keep his foot out of his mouth, but I don’t think he really intended to leave," Klopfer said.

The Duke University Archives has retained manuscripts of his travels in Madagascar. For instance, one time, Buettner-Janusch was fortunate to run into a pack of diademed sifakas, an endangered species of lemur.

"There were several adults and two juveniles, one quite young which clung to its mother's back. I shot several rolls of film, and they were reasonably good pictures," the manuscript stated. "One problem was that on this trip every damn animal seemed to sit in the trees with his/her back to the sun, so that I was constantly shooting against the light. The pictures are not good pictures, but they are extremely useful and were unique at the time."

However, when his wife died of cancer in 1977, Buettner-Janusch developed depression, according to the New York Times.

Two years later, as the chairman of the New York University anthropology department at the time, B-J was accused of using his laboratory as a "drug factory." Federal agents found that he and his lab assistants were manufacturing LSD and methaqualone.

Buettner-Janusch was indicted in 1979 and convicted in 1980 to five years in federal prison. Although he got off on parole in 1983, he soon would find himself back in prison.

In 1987, Buettner-Janusch sent poisoned chocolates to the federal judge who convicted him. The wife of the judge, Charles L. Brieant Jr., "fell seriously ill after eating four pieces of Golden Godiva candies but survived." He also sent "adulterated candy" to a former colleague from Duke and "authorities intercepted two other boxes."

A fingerprint on the box exposed Buettner-Janusch as the culprit. He was subsequently sentenced to 20 additional years in prison and pleaded guilty.

He died in prison in 1992 at the age of 67.

“We were in contact until the end," Klopfer said.

How the times have changed

Since Buettner-Janusch's departure from Duke, the DLC has expanded its reach beyond being a research center to also serving as a center for visitors.

Greg Dye, newly named executive director of the DLC who was also was director of operations and administration for 11 years, said that the DLC's incorporation into the broader Durham area is vital to its contributions to the community.

More than 60 volunteers come into the DLC each week to assist in some capacity, Dye said.

As executive director, Dye’s typical day varies but some aspects remain constant.

For example, he checks in with Cathy Williams, DLC curator of animals, to determine the progress of pregnant mothers and their babies. Dye also ensures that the DLC is receiving adequate funding from a variety of sources to provide the best possible life for its inhabitants.

Dye said that the DLC has dealt with recent hurricanes and flooding by constructing more durable facilities over each of the past two summers, yet fallen trees and lack of access to food still remain potential hazards to the lemurs.

With this in mind, Dye has increased the DLC’s supply of items essential to maintain a secure atmosphere, such as waterproof flashlights, headlamps and water barrels. Also, Dye has contacted food suppliers to purchase more food in cases of emergency.

The DLC also encourages current Duke students to come in and discover the center for themselves. It provides work-study opportunities as well as internships in animal husbandry, environmental education, communications and field research.

Students also have opportunities to join an existing research team or start their own project.

For senior Anna Lee, a double major in biology and evolutionary anthropology, the DLC has served as one of the defining aspects of her undergraduate experience. Lee, who will begin research on primates next fall in Kenya, explained that the potential to work at the DLC attracted her to Duke as a high school senior.

“[The DLC] reminds me that the world is way bigger than the campus bubble,” Lee said.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.