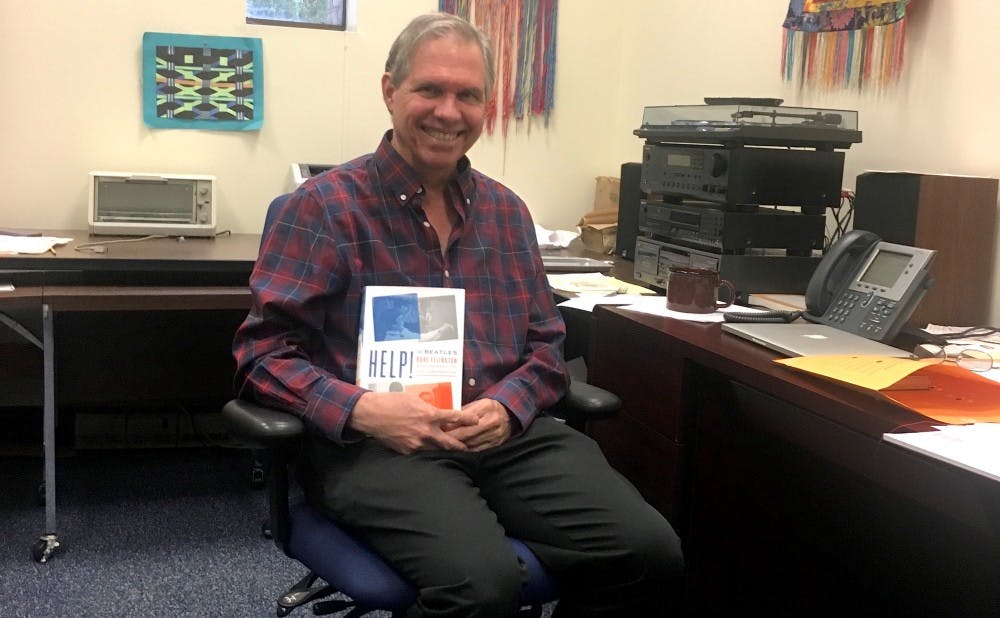

Like many of their artistic peers, famous composers are commonly panned as egocentric monomaniacs obsessed with their own genius. To challenge this myth, Duke professor Thomas Brothers recently published “Help! The Beatles, Duke Ellington and the Magic of Collaboration,” a new book dedicated to the methods of collective composition. Citing two seemingly unrelated groups — the Beatles, a British rock band, and Duke Ellington’s famous jazz orchestra — Brothers explores the various ways in which their music was a lot more than the product of singular brilliance.

“I often say that I’ve been working on this book since I was eight years old,” said Brothers, who became a lifelong Beatles fan after their performance on the Ed Sullivan Show in 1965.

A professor at Duke since 1991, Brothers got his doctorate in music at the University of California, Berkeley in that same year and serves as director of graduate studies within the music department. His work focuses on popular music and he has previously written about Louis Armstrong.

The new book’s title already indicates Brothers' main point: “Help!” is the title of the Beatles’ fifth studio album, as well as of one of their most famous songs. Written by Paul McCartney and John Lennon, its lyrics allude to the necessity of help, which may apply to life in general, but also to the particular endeavor of composition.

“When I was younger, so much younger than today/ I never needed anybody's help in any way/ but now these days are gone and I'm not so self-assured," Lennon and McCartney sing, emphasizing how, inevitably, we all require assistance at some point in our maturation.

“The only people who worked as closely as Lennon and McCartney were those two people at the bottom of the cover — Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn,” Brothers said.

Paraphrasing art sociologist Howard Becker, he writes that both the Beatles and Ellington’s works “could not have been achieved by a solitary composer, no matter how much coffee he drinks or how early he gets out of bed." Both relied heavily on an easy flow of ideas and came out of a specifically African-American tradition of communal music-making, which had also shaped such virtuosos as Louis Armstrong, Aretha Franklin and James Brown. Their method is to be sharply distinguished from the previous ways of classical music, in which a single composer’s notation had given each musician precise instructions. Brothers stresses, however, that neither method should be lauded as superior. Instead, he writes, "we should seek to understand their differences."

Beginning with detailed historic treatises, the book traces the two groups’ respective foundations and their workflows, which Brothers calls a “division of creative labor” that has since become the norm for popular music. Ellington, for example, is often exalted as the greatest American composer of the 20th century, but Brothers points out the importance of trumpet and cornet player James “Bubber” Miley, of whom little is known. Comparing them to painters Pablo Picasso and and Georges Braque, Brothers argues that their work is in fact almost inseparable, with each one continuously imbuing the other.

“He’s at the center of the process but he’s not necessarily the guiding vision," Brothers said of Ellington's approach to writing.

Brothers likens Ellington’s decentralized work scheme to that used for the 1939 movie classic “The Wizard of Oz.” Instead of being dominated by a singular “auteur,” the movie employed 10 different screenwriters and four directors, who each contributed their own perspectives.

“Ellington was in charge, but an egalitarian spirit was in place,” writes Brothers, concerning the orchestra’s shaping arrangements, although he could be more assertive in pieces that were less connected to jazz or dance. In a subsequent chapter, Brothers explores the interplay of Ellington and fellow composer Billy Strayhorn, who was well acquainted with Martin Luther King but remained an elusive figure because of his open homosexuality.

Brothers also devotes extensive attention to the unique cooperation of John Lennon and Paul McCartney, who worked together so closely that they decided to cosign every one of their compositions, regardless of each one’s individual contribution. The author sketches the group’s evolution from its early Hamburg years to its later struggles with megacelebrity, as well as drug-fueled episodes of excess and provocation. Another focal point is record producer George Martin, who had an enormous influence on each Beatles album and set the example for the now ubiquitous producer’s role.

In spite of its academic subject, Brothers’ prose flows smoothly and eschews the terminological obscurities that characterize many book-length works of criticism. Rich with quotations from acquaintances and appropriate imagery, the reader is drawn back into the '60s and its notorious debauchery, with remarkably cogent storytelling elucidating their artistic and social conditions. The myriad of copyrights surrounding the Beatles’ legacy, however, complicated the book’s development, as Brothers was not allowed to directly quote lyrics or use photographs without explicit permission.

For a semester-long experience in similar musings, interested students can spike up their spring bookbags with the matching class, since Brothers will be teaching a course on the Beatles and the 1960s.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.