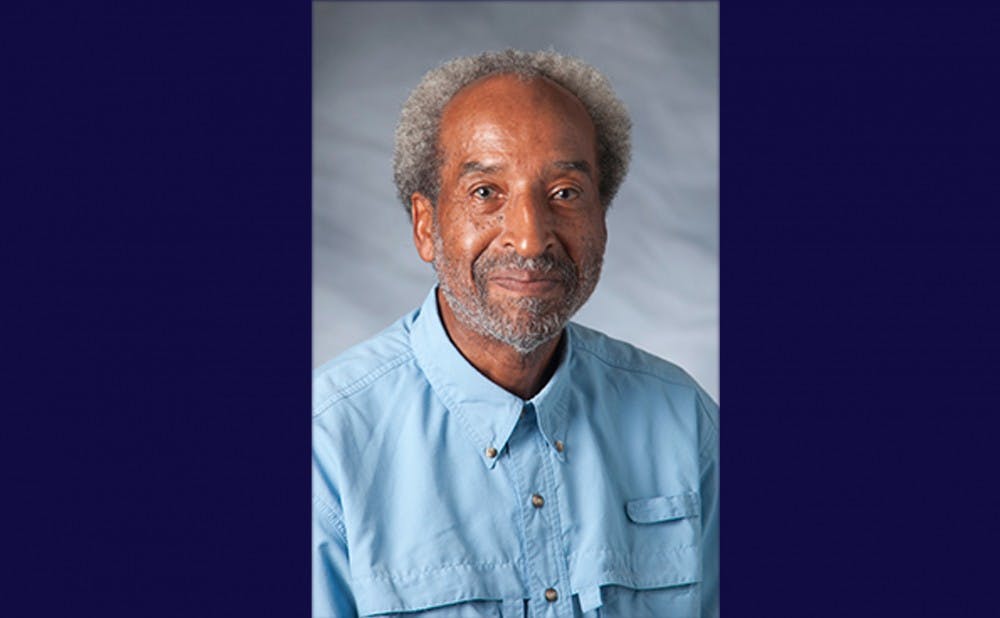

As support for removing the Carr Building's name continues to grow, here's a look at the legacy of the man the history department wants to rename it for.

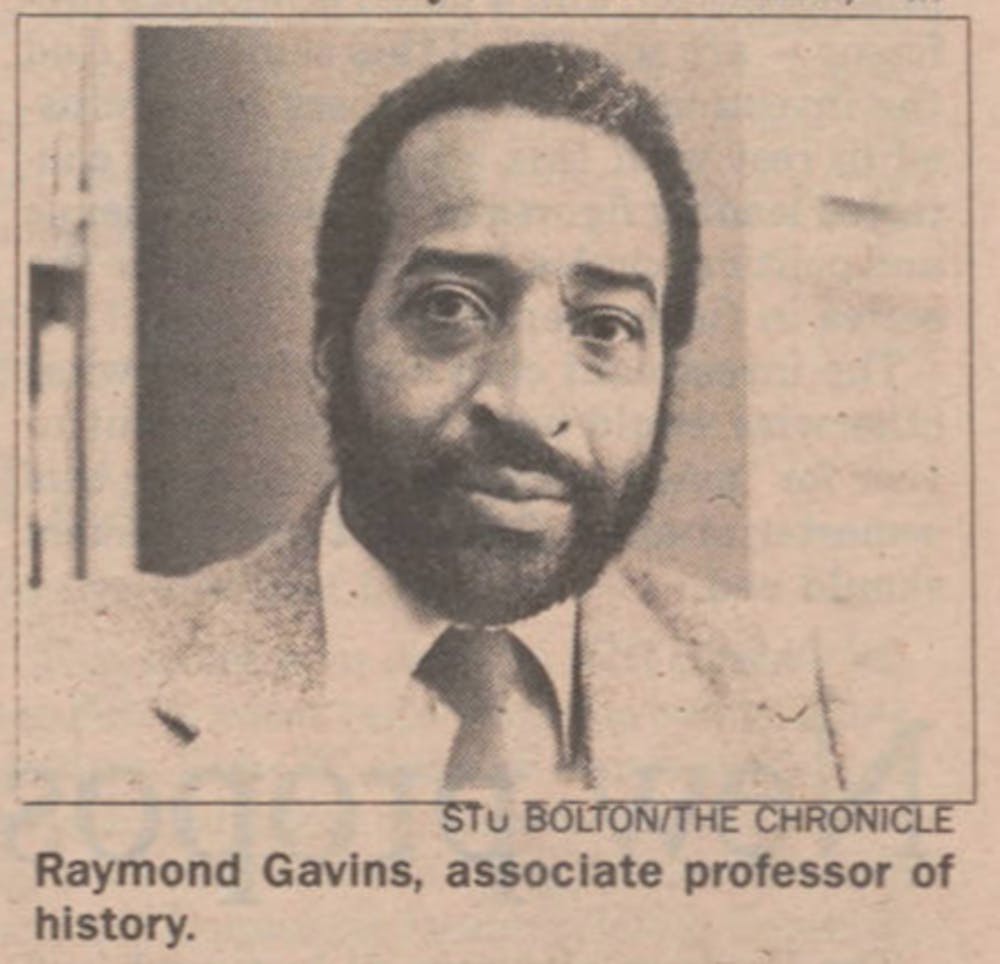

In late August, the history department submitted a proposal to the Board of Trustees, recommending that the Carr Building be renamed after Raymond Gavins, the first African-American history professor at Duke.

One-hundred forty Duke history alumni also signed a letter submitted to Richard Riddell, senior vice president and secretary to the Board of Trustees, earlier this month denouncing the namesake of Julian Carr, a “virulent white supremacist” who donated Blackwell Park to Trinity College, allowing the college to move to Durham in 1924 and become Duke University. They also unanimously recommended Raymond Gavins as a new namesake for the building.

Gavins joined Duke’s faculty in 1970, becoming the first African-American faculty member in the history department. His students say he not only shaped the trajectory of the department, but served as a mentor and role model for students during his 46-year tenure at the school. Gavins died in 2016.

Born in Atlanta, Ga., Gavins was the seventh of eight children in his family and went on to pursue his higher education at the Virginia Union University in Richmond, Va., until his graduation in 1964. He then earned both his master’s and Ph.D. degrees in history at the University of Virginia, becoming the first African American to earn a Ph.D. in the history in the university’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in 1967.

Gavins taught Duke's first course in African-American history in the Fall 1970. Waldo Martin, now the Alexander F. and May T. Morrison professor of American history and citizenship at University of California at Berkeley, said he remembers taking the class as a sophomore.

“I think it was one of the key inspirations on my road to becoming a historian. I’m not sure I would have become a historian if I hadn’t taken Ray’s class. I didn’t really like history that much,” Martin, Trinity ‘73, said. “Ray’s class inspired me. I saw myself in that class.”

Joining the Duke faculty at a time when there were only a handful of African-American students at the University, Gavins made mentoring scholars of color a priority.

“I believe Dr. Gavins should be honored by having the Carr Building renamed for him because he worked tirelessly to diversify the historical profession within the academy,” said Crystal Sanders, Trinity '05 and associate professor of history and African American Studies at Pennsylvania State University, for whom Gavins served as her Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellowship advisor as well as her honors thesis advisor.

As an African-American woman from a rural small town in eastern North Carolina, Sanders said it was very important for her to see someone in the history department who was not white.

“Representation matters, but it wasn’t just seeing him—he encouraged me and told me I had what it took to be a historian and enter the historical profession as a scholar, educator and author,” Sanders said. "Him believing in me allowed me to believe in myself."

Gavins’ pioneering work helped create the field of Afro-American history and highlight the importance of social history and oral tradition. He also made African-American history classes at Duke popular.

According to his former students, Gavins impacted thousands of students with the message of pursuing truth in African-American history beyond the scope of the implementation of white supremacy but also studying social history and oral traditions to record the people’s history.

His groundbreaking scholarship included cofounding the Behind the Veil project which documented oral history interviews of African-American life in the Jim Crow South from the 1890s to the 1950s. He also helped launch the history department’s Oral History Program.

Now teaching at Georgetown Law School and writing legal history, Brad Snyder, Trinity '94, said Gavins inspired many of his current endeavors.

“His office was an intellectual greenhouse and the door was always open as he supervised my honors thesis for three years. His classes changed my life," Snyder said. "He was my biggest fan. I miss him so much. I wish I could tell him about what’s going on in my life. I dedicated my second book to him."

Philip Rubio, Graduate School ’06, said Gavins encouraged students to examine history critically, which is exactly what students did by challenging of the landscape of confederate monuments and through the later demonstrations on campus were.

Braxton Shelley, Trinity ’12 and assistant professor in the music department at Harvard, said he credited Gavins for the nuts and bolts of his academic foundation.

“Renaming the Carr building in his honor would be a fitting tribute that would point to some of the work he did in nearly half a century on the faculty. It’s a no brainer and I really hope to see it happen,” Shelley said. “Very rarely a week goes by where I don’t think about him…that really inestimable amount of impact is certainly worthy of a building.”

Editor's note: This article was updated to include Sanders' current academic affiliation.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.