“Are there black men in prison in the Durham County Jail because Duke students use drugs with relative legal impunity?”

The question lingered, met with silence from students. Adam Hollowell, adjunct professor in the Sanford School of Public Policy, asked it during a class exercise in his annual course "Ethics in an Unjust World." Hollowell sought to capture the relationship between drug use on college campuses and the broader structural realities of drug arrests and sentencing in America, outlined in books like Michelle Alexander’s “The New Jim Crow.”

Before posing the question, Hollowell asked students to assume they had $100 and the desire to buy an illegal substance. He framed the situation as hypothetical to keep it free of judgment. He asked whether students feasibly could purchase drugs in the Sanford School building within two hours—without leaving the building, with the ability to use their phones. Students circled yes or no on paper, and folded and submitted their responses to keep the survey blind.

Ninety-two percent of students wrote yes.

Hollowell has posed the same question to his class every year, with responses ranging between 70 and 92 percent. Although he said that students seemed unsurprised by the results, they demonstrated greater resistance to conclusions he drew from the survey.

He asked students if these interactions would classify the Sanford building as a drug market, or if this meant that Duke students were drug dealers. In both cases, students hesitated to respond in the affirmative.

“I am genuinely curious about how drugs flow into this campus, what the repercussions are of that drug flow for the broader community and the ways that race and racism play into who faces which consequences for illegal drug use on campus,” Hollowell said.

Blacks and African-Americans comprised 37.2 percent of Durham County’s population in 2016, according to the Durham County website. In contrast, 7 percent of Duke’s student body is black or African-American.

Hollowell has spent the last seven years teaching at Duke, where he also earned his undergraduate degree in religious studies and philosophy in 2004.

His class exercise portrays a student body that does not often consider those outside our institution who enable our lifestyles—the people who cannot write their own rulebooks.

We are taught to criticize, analyze and deconstruct systems of power in the classroom. But applying the same logic to evaluate the balance of power between Duke and Durham reveals that our academic ideals might diverge from our lived decisions.

We distance ourselves far from the language of addiction, incarceration and crime. Inside Duke’s walls, we are Duke students: ambitious, invincible, blameless.

A consistent relationship

Twenty-seven days, 106 text messages.

Between October 26 and November 22, a Duke student exchanged 106 text messages with one contact. During the same time period, he exchanged just a few more messages with his mother: 120.

This person is not his girlfriend, his best friend or his lab partner.

He is the student’s cocaine dealer.

Requesting anonymity for legal protection, the student estimates that he has probably exchanged thousands of text messages with various dealers throughout his time at Duke.

The student, who is a white male, said he usually smokes marijuana two to three times a week. He uses other drugs approximately every other week—most frequently cocaine. He classifies himself as a regular drug user.

The student does not directly interact with his marijuana dealer, but he knows his cocaine dealer well. He said the man has “strangely become a friend.”

He said he feels more comfortable buying drugs from the dealer who he knows more closely. This dealer is similar to the student in terms of socioeconomic background, ethnicity and education level. He knows this dealer has other revenue streams to comprise a safety net.

When questioned, the student said he could not separate his drug consumption from the larger issue of mass incarceration. He thinks every customer bears responsibility.

Many of the dealers he has interacted with in Durham are black. The student acknowledged that mandatory minimum sentences disproportionately affect blacks and African-Americans.

He described his nonchalant attitude toward purchasing drugs.

“A cop seeing me driving is most likely never going to pull me over unless I’m doing something egregious, so I’ve never felt like I was ever at a significant risk of getting in trouble,” he said. The student said this is largely a function of his privilege as a white male.

He also said he would feel worse about implicating a black dealer than a white dealer.

Police officers demonstrate a greater likelihood to stop, search and arrest black or Latino drivers than white drivers, according to an analysis carried out by Stanford University researchers. Police abide by a lower threshold of suspicion to search minorities during routine traffic checks.

This national pattern has been observed in Durham. Black drivers in Durham were searched more frequently than white drivers, according to Durham Police Department Stop-and-Search Data published by the Southern Coalition for Social Justice in 2013.

Black and Latino offenders are more likely to be incarcerated than white offenders, according to the ACLU. Black males also get longer sentences than white males arrested for the same crimes with similar criminal backgrounds.

The student said he prefers to obtain drugs for himself rather than relying on friends as intermediaries. He likes to have agency over the situation so others cannot be blamed.

He said that if a dealer were to be caught by the police for a transaction involving him and his friends, his first emotional response would be to feel concern for his friends. However, he believes the dealer would face the greatest risk.

“If I were to reflect honestly on who I am the most concerned about facing legal trouble, or actually like having a life altering-experience from it, it would probably be the original source [of the drugs],” he said.

The student said that he and his friends have access to resources, if a situation with legal repercussions arose.

“We have parents that—at the end of the day—are going to sit down with us and help us get lawyers...we’ll probably get some sort of community service assigned to us, and it will be wiped off our record. Other people don’t have those resources.”

Previously, he has never given much thought to who bears degrees of risk during these transactions, he said.

'A part of this system'

A conversation with another student, a white female who also requested anonymity for legal protection, revealed a similar risk assessment. She considers what is at stake for herself and other people she is with when she uses drugs, but does not initially think about the dealer’s circumstances.

In a message, she wrote that she uses marijuana seven days a week in addition to occasionally using other drugs. She obtains marijuana from a Durham resident who supplies many Duke undergraduates.

They communicate through text messages and typically meet every other week at a specified location on Duke’s campus. The student wrote that she feels comfortable buying drugs on campus, but not elsewhere in Durham.

She asks friends to go into the dealer’s car, so she and the dealer have not met face-to-face. She has little background information about him and would not want to know more, she wrote. She does not want their relationship to be a close one.

“It always made me a little uncomfortable to be in such close quarters with someone doing something so blatantly illegal,” the student wrote. “Which is ironic, because me buying drugs from him was just as illegal.”

She also reflected on whether she believes her consumption of marijuana is related to increasing rates of incarceration.

“During the act of smoking or interacting with my dealer, I have never thought about the risk that he is putting himself at and the role that I am playing in that risk,” she wrote. “Maybe that’s because I am selfishly thinking about the risk I am at personally. That being said, the people who the dealer is supplying to are inherently necessary in the drug deals they are incarcerated for.”

“I am absolutely a part of this system,” she wrote.

The student noted that a security guard once caught her smoking marijuana on campus and called DUPD. After the student admitted to her actions and repeatedly apologized, authorities did not note the incident on her record. This incident has not affected her current habits, she wrote.

On Duke’s campus, degrees of separation exist between actions and implications. It is easy for students to pay no heed to consequences when they affect people who we do not see.

Navigating structures of power

The first student is involved with numerous extracurricular activities at Duke and hopes to pursue a career in politics after he graduates in May.

The second student has a near-perfect grade point average and has advocated for various social causes throughout her college years.

Both are ambitious and involved in campus culture, successful by Duke’s metrics.

When it comes to legal trouble versus disciplinary trouble at Duke, the first student said he would be more worried about his academic standing. He would not want to jeopardize his reputation as a student.

The student said he is under the impression that Duke’s administration is fairly willing to work with students who are prepared to confront their issues and follow through with corresponding steps, like going to Counseling and Psychological Services or other mandated programs.

Because college students are undergoing formative years in terms of character and habit development, he believes Duke’s approach to drug use makes sense.

“I do think obviously, that when problems get serious, Duke can be very serious,” he said.

John Dailey, DUPD chief of police, wrote in an email that the underage possession of alcohol and the possession of a small amount of marijuana have been a low enforcement priority of the department. DUPD prefers to use the student or employee conduct process for scenarios without aggravating factors, he explained.

“We do not believe this to be a great use of the court system,” Dailey wrote. “We have systems on campus for students and employees that can impose an appropriate corrective action. The same violation off campus may result in a different process, as there is not an alternative to the court system.”

Dailey wrote that the police document the incident, but do not determine whether sanctions will be issued.

According to the Student Conduct website, disciplinary hearings differ from trials and are not subject to the same rules of procedure, evidence or standards as the court system.

Dailey noted that the assistance of an attorney who understands legal processes can make the court system easier to navigate. He wrote that it appears as though the Durham Police also regard the enforcement of minor quantities of marijuana to be a low priority.

Institutional accountability

Data published by the University reveals a disparity between the number of drug referrals at Duke and resulting arrests. Students are not punished for every incident report documented by a resident assistant, security guard or police officer—just as defendants are not always convicted in criminal court.

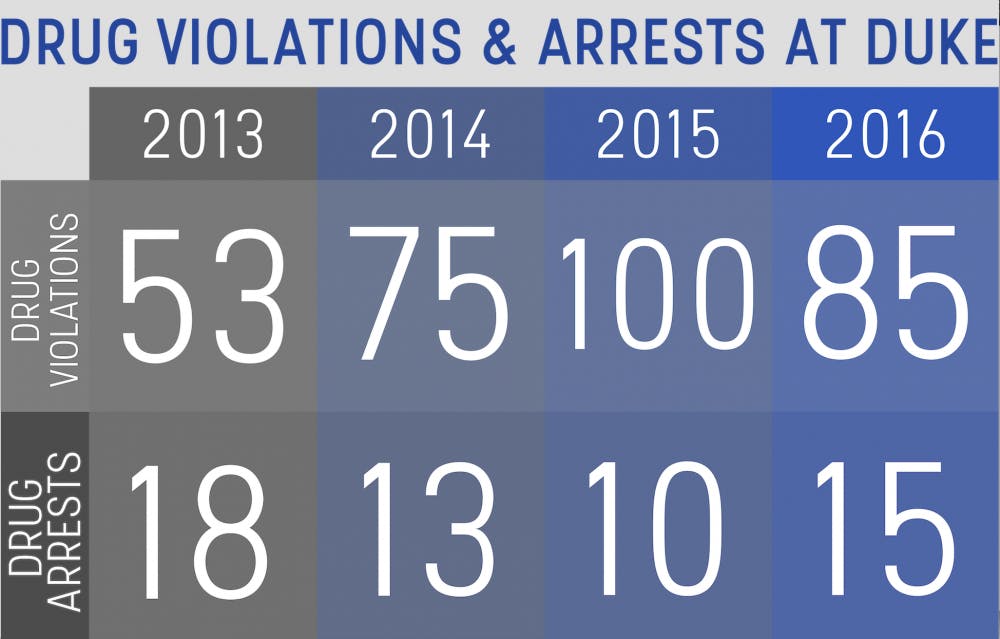

According to the federally mandated Clery Act Annual Security Report, Duke referred 53 drug violations in 2013. Eighteen cases led to arrests.

The University referred 75 drug violation cases and made 13 drug arrests in 2014, and referred 100 cases with 10 arrests in 2015. In 2016, there were 85 referred violations, which resulted in 15 arrests.

The percentage of violations leading to arrests ranged from 10 percent to approximately 34 percent.

The Clery Act is released each October and includes data from the previous year. The University also releases yearly Undergraduate Disciplinary System Statistics Snapshots, which provide data about student conduct processes.

According to Stephen Bryan, associate dean of students and director of Duke’s Office of Student Conduct, the typical sanction for possession or use of a small amount of marijuana is disciplinary probation for a specific duration of time. This sanction is accompanied by referral for substance use assessment and education, he wrote in an email.

However, evidence of distribution or sales could lead to suspension, Bryan wrote. Expulsion generally would be considered in repeat instances or other aggravating factors.

According to the yearly snapshot, OSC recorded 94 incidences of “Drugs and Drug Paraphernalia” during the 2013-14 academic year. OSC found 39 students responsible at a rate of 41.5 percent.

OSC recorded 133 incidences in 2014-15, finding 59 students responsible at a rate of 44 percent.

In 2015-16, OSC reported a rate of 121 incidences, finding 45 students responsible at a rate of 37.2 percent.

OSC processed 121 incidences in 2015-16, with 45 students found responsible at a rate mirroring that of the previous academic year.

Dailey wrote that the disparity between referrals and arrests on campus likely exists because the number of referrals in the Annual Security Report includes reports from residence assistants and other campus security authorities beyond the campus police. Most of the reports result from resident assistant documentation and did not involve DUPD, he wrote.

Residence assistants are instructed to act based on whether they suspect or are certain that a resident possess drugs or is dealing them, resident assistant and senior Olivia Deitcher wrote in a message.

Residence assistants must follow a standardized flow chart that includes knocking on the door, asking specific questions and documenting the situation through incident reports. They report the facts but do not determine whether the student engages with the residence coordinator or student conduct. Residence assistants immediately call DUPD and the residence coordinator to handle the situation if a student has previously been documented for drug use.

Deitcher explained that supervisors do not instruct residence assistants to proactively seek out policy violations. However, if they smell marijuana use, see drug usage or view drug paraphernalia, they are obligated to document the incident.

Overall, Deitcher believes Housing and Residence Life’s policy is reasonable. From her standpoint, the dialogue that students have with the RC or Student Conduct appears to be community-centered rather than focused on shaming habits.

“HRL has never told RAs to go on a witch hunt,” she wrote.

If caught, the dealer who delivered those drugs likely will face a court system that is less forgiving.

Any distribution of marijuana exceeding five grams is treated as a felony in North Carolina, according to the website of Raleigh-based law firm Hatch, Little & Bunn, L.L.P.

The motives behind administrative and DUPD policies cannot be presumed. However, at least one conclusion can be drawn: when caught with drugs, sometimes students are afforded second chances.

But once students grow accustomed to leeway, will circumstances ever force us to shed these expectations during life after Duke?

The first student discussed how he is passionate about progressive causes, but he thinks others have difficulty reconciling his convictions with his behavior. He looks forward to being forced to live out his beliefs when he enters the workforce and encounters new communities.

The student believes that being constantly surrounded by 18 to 22-year-olds insulates students’ attitudes. He said he might change his drug habits if he had a neighbor with young children, who had witnessed him using drugs.

“If I felt like I was adversely affecting the people who live next door to me…that would probably curb [my drug use],” he said.

The student also thinks that knowing the specifics of who would be implicated or arrested for students’ drug use would influence students’ habits. He believes Duke students generally are empathetic, but that they feel shielded from actions that extend beyond campus.

“I think that a lot of us feel that because we’re in the Duke bubble, within Durham, we aren’t responsible for what happens outside of the Duke bubble,” he noted.

He believes attitude drives students toward more open drug use.

“Especially in Durham, Duke students are sort of masters of the universe,” he said.

Outside of the bubble

“What was your bottom?”

Elisha McLawhorn, TROSA graduate and staff member, said this question is frequently asked at TROSA. TROSA is a multi-year residential program in Durham that allows substance abusers to rebuild their lives through comprehensive treatment, vocational training and continuing care.

Effectively, the question translates to, “What brought you to TROSA? What caused you to make these shifts in your life?”

McLawhorn said that the socioeconomic backgrounds of TROSA residents vary significantly. The program includes residents who grew up in wealthy families, pursued law degrees or business degrees and had successful careers before coming to TROSA.

“Addiction doesn’t discriminate,” she said. “It doesn’t care if you come from a nice family; it doesn’t care if you come from a poor family.”

She spoke about how facing accountability early in life can shape people’s behaviors, decisions and expectations with regard to drug use down the line.

“If they’re never held accountable...young adulthood can be very shocking,” she said.

However, McLawhorn noted that those with status may feel protected because their families get the best lawyers and leverage connections in adverse situations. As a result, run-ins with the law might leave certain users to face only a “slap on the wrist.”

“I think everyone deserves a second chance, but not everyone gets one,” she said.

She said that high-achieving, functional drug users can only juggle competing interests for so long. But the collision between reality and repercussions may come slower to those with unconditional support systems. She would not expect drug users who have always been enabled to expect heavy punishment.

So what ends up shattering that sense of invincibility?

“It just depends on if they run across somebody that’s not going to allow that to continue happening," she said. “At some point in your life, you’re going to come across someone who will…set boundaries with you.”

McLawhorn said that drug users from poorer families might face more challenging pitfalls than those with access to resources, but all people face the same core susceptibility to drug use.

“Whether you go to Duke or whether you go to Durham Tech, you’re a human being. All human beings are fallible,” she said.

McLawhorn believes it is important for everyone to learn about homelessness and addiction, regardless of whether people feel separate from these issues. “There are homeless people standing on the corner, and you have no idea what led them to that point,” she said.

The first student said that if he were to pass by a person dealing drugs in downtown Durham, he and his friends might make derogatory assumptions about the person’s character or background. However, he said those comments would not reflect how he or his friends actually feel.

“I’m very aware of the fact that the one-in-ten-billion chance that I happened to be born into the family that I was born into affected the way that my life went,” he said.

McLawhorn noted that TROSA participants could offer insights to a Duke student.

“No one, no matter what kind of economic background they come from, nobody’s guaranteed anything,” she said.

Fragile, fallible, human

Hollowell said that University initiatives like DuWell help students approach questions of recreational drug use in terms of personal health and wellness. However, he does not believe Duke frames the risks or implications of drug use as an issue involving lives of people in the Durham community, or even as a broader social or community issue.

He does not necessarily hold students responsible for that lack of consideration.

“After all, students consider what we as a University invite them to consider,” he said.

Institutional structures make it so that attaining the benefit of the doubt is never fully out of reach for Duke students. As a result, many operate as though they live outside the scope of the law.

Would students act differently if we were forced to more deeply consider the ripple effects caused by this invincible attitude?

Perhaps yes, perhaps no. But hopefully we would think within a framework larger than that of our distorted world, and at least act with awareness about how our lives are intertwined with the lives of others.

Should students be capable of undertaking this consideration ourselves, without prompting from an institution?

Yes—but when instinct fails, power structures can provide insight.

Beyond Campus Drive, Duke students are not masters of the universe. Ultimately, we will face life’s storms as anybody else does: fragile, fallible, human.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Carly Stern is a Trinity senior. Her column, "never been satisfied," runs on alternate Fridays.