A century ago, John Kilgo, former president of then Trinity College and chair of the Board of Trustees, ended his association with the University.

Although most students are familiar with Kilgo as the quad closest to West Union, the name comes from a well-known bishop who served as Trinity College’s fourth president from 1894 to 1910. Later, he was a member of the Board of Trustees between 1910 to 1917 and also served as its chair.

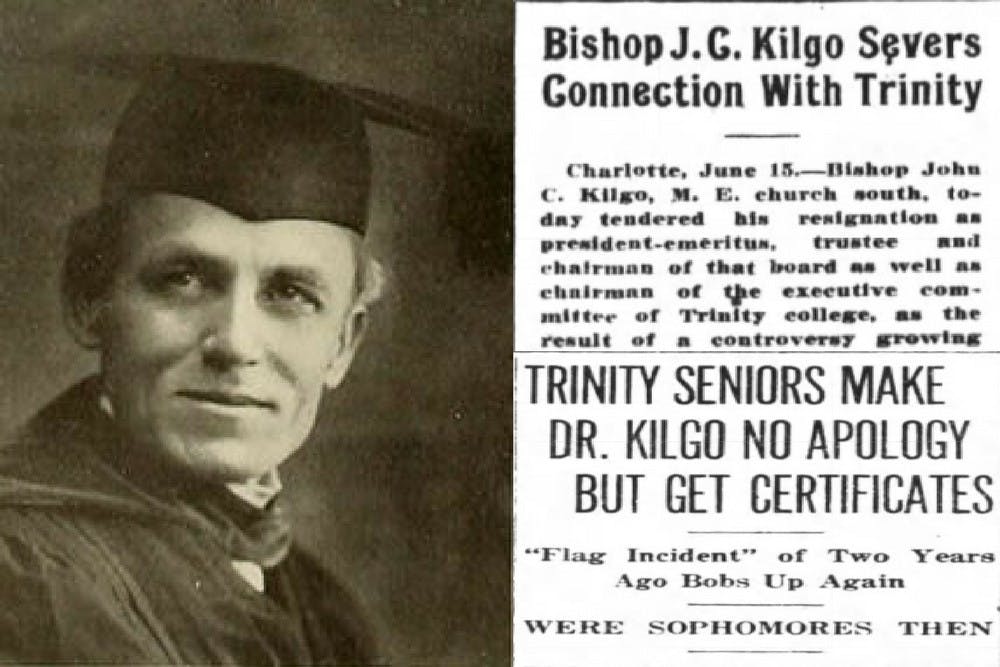

Because he had so many connections to Trinity, it was shocking to the University community when an article appeared in the Greensboro Daily News on June 16, 1917 reporting that Kilgo had severed his “connection with Trinity.”

“All intelligent and fair-minded persons must know that, judged in the light of nearly 25 years of devotion and unselfish service to Trinity College, a devotion which the record puts beyond challenge, only the most vital reasons could have moved me to take this step,” Kilgo wrote in a local paper in 1917.

Through letters, speeches and other historical documents found in the Duke Archives, The Chronicle pieced together the dramatic series of events that led to his statement.

The ‘buffalo class’

Understanding Kilgo’s decision requires understanding what The Chronicle once called “the long-lived contest between [Kilgo] and the Class of 1917,” which began on Thanksgiving night 1914.

On that Thursday evening, someone “hoisted a large flag bearing the figure ‘17’” to the flag staff in the center of campus, according to a Greensboro Daily News report. When Kilgo saw the flag outside Craven Memorial Hall—a building that was destroyed by fire in 1972—he was angry.

The following Monday, he made a speech condemning the action, calling the perpetrators “traitors, buffaloes, cowards” and “sons of Benedict Arnold,” according to the Greensboro Daily News report. Kilgo further said that there was a “stain on the Class of 1917,” which he would from then call the “buffalo class.”

“The bishop concluded by saying that unless the guilty one was ferreted out and sent away as a traitor to his country and a blot to Trinity, he would sever himself from the college, erase the name of Trinity from all his belongs and spend the remainder of his life in apology,” the report noted.

Upon hearing Kilgo’s remarks, the Class of 1917 adopted a resolution resenting “unwarranted interference by an outsider who occupies no executive position in the college management.” Kilgo had stepped down from the office of president four years earlier, although he was on the Board of Trustees.

“The sophomores in class assembled say that the class as a whole was not responsible for the prank and do not think the whole class deserves to be put into the ‘buffalo, scoundrel and sons of Benedict Arnold’ column,” a Greensboro Daily News report in December 1914. “They adopted a set of resolutions in which they say that they do not believe that it is business of the class to ferret out the man or men who did this deed. The class also resents Bishop Kilgo’s ‘unwarranted interference’ in college affairs.”

Kilgo wrote to a Trinity alumnus, whom he called Mr. Andrews, arguing that the class in fact knew who the perpetrators were and lied about it to the public. He added that he could not tolerate students lying and thought those that attended Trinity College had better character.

“IT WAS THE FALSEHOOD AGAINST WHICH I WAS MOVED,” Kilgo wrote in all capital letters. “I have always been willing to be patient with every form of wickedness except falsehood. A man who will not tell the truth has in him no foundation upon which to work.”

The “buffalo class” graduates

The flag incident stuck with Kilgo for many years. In a letter to Mr. Andrews in December 1917, Kilgo recalled “a steady growth of serious misconduct among the students” to contextualize the flag incident.

“Vandalism, disregard for administrative regulations, making sport of somethings which should always receive respect from Trinity students, drinking, card playing and even having prostitutes in the dormitories,” Kilgo wrote. “Of course these things were rebuked but they did not cease, especially in some of them. All this was to me signs of peril and causes of sore grief.”

Two years after the flag incident, the Class of 1917 was graduating, and commencement became a tumultuous affair.

In April 1917 before graduation, members of the Class of 1917 wrote to Kilgo after he received an offensive letter from someone claiming to be a part of that class.

“It is the unanimous desire of the Class to express to you its profound humiliation and regret at this occurrence which is at once an insult to the Seniors Class and to one who was served the College so faithfully and so well,” the letter stated. “It is furthermore the sincerest hope of the Class that you will not for a moment believe that any such sentiment as must have prompted the writing of such a letter is present in this body; but that you will understand that this Class cherishes for you only feelings of deepest loyalty and respect.”

According to his letter to Andrews, Kilgo—then chair of the Board of Trustees—asked President William Few to speak to the Class of 1917 before commencement to see if they still stood by their original statement about the flag.

“I care nothing about their opinion of me. It is not a personal matter,” Kilgo wrote. “It is wholly a matter of moral policy in Trinity. If they will withdraw the statement that there is no proof that it was done by members of their class, I have not one word more to say.”

Few told Kilgo that he spoke to the class and they stood by their previous resolution. For Kilgo, this meant the class condoned the falsehood, something he found so unacceptable that he could not vote for the male members of the class to graduate and would not sign their diplomas.

However, the members of the Class of 1917 still graduated. Joseph Brown, who would become chair of the Board of Trustees after Kilgo, signed their diplomas. The next morning, Kilgo offered his resignation, but the Board declined to consider it.

For a while, Kilgo put his desire to resign from the Board to rest.

The ‘crack brain’ reporter

Kilgo’s speech at commencement and decision not to sign the diplomas caused quite a sensation in North Carolina. One reporter, W. T. Bost of the Greensboro Daily News, was particularly interested in Trinity’s affairs.

On June 10, 1917, Bost wrote a scathing account of the events at commencement in an article with the headline “Trinity Seniors make Dr. Kilgo no apology but get certificates.”

The day after, Few wrote to Kilgo, emphatically expressing his support of Kilgo. He wrote that he did his best to keep the recent commencement out of the newspapers.

“I am infinitely sorry that you have had to be harassed with all this,” Few wrote. “But I hope that you will allow it to trouble you just as little as possible; and I am going to do the same. I am sorry I could not have managed it better, but I have done my best; and I shall have to depend upon the good Lord as I have in other trying occasions.”

Few wrote that he wanted to prepare a statement to print in the Daily News about the events that took place at commencement. However, a man affiliated with the University and W. Duke and Sons company—whose name is illegible on the document—wrote him saying that submitting a statement would feed Bost’s ego.

"Mr. Bost is a ‘crack brain’ irresponsible newspaper reporter, who would consider it a great compliment if his article should bring forth a reply from you or any other responsible man,” the man wrote.

According to Kilgo’s letter to Andrews months later, he felt Bost’s reporting was unfair and said the fact that the University did not do anything about it was a betrayal.

“The most untrue matter was evidently furnished [Bost], and he wrote articles attacking me and saying things that were to my mind, abusive.” Kilgo wrote. “Yet not a word was spoken against by the Trustees or by the administration.”

A week after Bost’s article came about, Kilgo cut his ties with the University, which included an end to preaching and advising students as well as his resignation from the Board of Trustees and his role as president-emeritus. He explained his decision in the letter to Andrews.

“I decided as I had taken patiently abuse for Trinity College, and then abuse by Trinity College of the latter I had enough, and I was determined to force the real attitude of the college toward this sort of conduct,” Kilgo wrote. “I resigned. I gave no reason for my resignation.”

Upon hearing news of Kilgo’s resignation, Few hastily wrote to Kilgo, expressing his regret for how the events unfolded.

“I take literally the first opportunity to write you, and there is not much to say now except to tell you that I’m sorry, that in the sad shape the Board may find it possible not to accept your resignation, that you must not desert us just because you think we have blundered, after all these years of work and sacrifice together in a great and inspiring cause,” Few wrote. “Believe in us and give us a chance, and it will all come out right in the end.”

Kilgo also wrote to Andrews that Bost was a paid publicity agent of the University. Dallas Newsom, treasurer of Trinity College, wrote to Kilgo that in December 1916 that the Executive Committee of the Board of Trustees authorized a payment of $20 a month—almost $420 today—to Bost for six months for “his services in giving publicity to the College during her quarter-centennial.”

“The kind of publicity that we have all gotten has been a disgrace to the newspaper profession, and must react on the profession,” Newsom wrote. “All of this business has been a deep grief and regret to me. It pains me to know that you have been made to suffer at the hands of those who should have borne you a heart of gratitude.”

On Nov. 21, 1917, the Board of Trustees approved Kilgo’s resignation. Few and Newsom both expressed to Kilgo in letters that history would vindicate his actions.

“The time will come when all this will appear to you in better light,” Few wrote. “It is inevitable that you should have disappointments in the College as in every human being and in every institution in the hands of human beings. But you are going to find that the College will always wear an appreciation of your services your devotions, and your faiths, in its very heart of heart.”

Correction: This article was updated 10 p.m. Monday to reflect that Craven Memorial Hall was not on East Campus when it was destroyed by fire.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.

Class of 2019

Editor-in-chief 2017-18,

Local and national news department head 2016-17

Born in Hyderabad, India, Likhitha Butchireddygari moved to Baltimore at a young age. She is pursuing a Program II major entitled "Digital Democracy and Data" about the future of the American democracy.