This is the fifth story in a multi-part series on the student conduct process. The first story examined the experience of one student who went through the student conduct process and felt she was treated unfairly. In the second story, two legal experts criticized the student conduct regime. The third story, published two weeks ago, detailed additional students’ experiences with the Office of Student Conduct, and the fourth story, which was published last week, explored the intersection of student conduct with the University’s alcohol policy. If you have had experiences with the Office of Student Conduct that you would like to share with The Chronicle in a confidential manner, please contact Claire Ballentine or Neelesh Moorthy.

Several students who have gone through the University's student conduct process and lawyers who have interacted with the Office of Student Conduct say that there are significant flaws in Duke’s disciplinary process.

Duke students who spoke with The Chronicle, along with a Duke Law professor, and a Durham lawyer who defends students in the student conduct process criticized the process for having hostile administrators, overly-severe punishments and undergraduate conduct boards predisposed to finding students responsible.

Students who work with the Office of Student Conduct—as panelists on the UCB or as student disciplinary advisors—have a different viewpoint. The Chronicle reached out to about 50 former UCB panelists and disciplinary advisors, as indicated by their LinkedIn profiles or OSC’s website. The majority declined to comment or did not respond, but those who did respond defended the process against some of the criticisms made by students who went through the process and lawyers who have interacted with the process.

“The process is extensive. If you were not at fault, it will 99.9 percent of the time find you that way,” said Lorenzo Babboni, Trinity ’17 and a student disciplinary advisor tasked with helping students navigate the process, who did not sit on the UCB. “In my experience, people who go through this process did do something they shouldn’t have done, they regret doing it, were under stress and caved momentarily. They didn’t do something major, and oftentimes they need to go through the process to make sure they understand they did something that Duke says is not a student quality they want to be promoting. It’s not perfect, but I think it’s a pretty good system for what it is.”

Defending the UCB

Some students say the undergraduate conduct boards are biased against accused students. A UCB panel typically consists of three students and two faculty or staff members and makes determinations of responsibility when a case has not been resolved by either an administrative or faculty-student resolution.

For example, one student accused of cheating—later found not responsible on appeal—called the UCB hearing “the absolute worst part” of her interaction with OSC. Donald Beskind, a professor of law and faculty advisor since 1977, said that UCB panelists are often more interested in “prosecuting” a student than making an impartial determination of guilt.

And another student who was caught shoplifting accused UCB panelists of being “self-selecting” and the type of students who “derive some kind of enjoyment from punishing other students.”

Other students who previously served on UCBS pushed back against the charges of UCB bias, saying that their motivations for joining the panel were not to punish others.

Julia Bretz, Trinity ’17, served on three or four cases and said she considered it an “honorable position” and wanted to uphold the integrity of the community. Dalton Brown, former UCB panelist on six to eight cases and Trinity ’15, also noted that he wanted to make Duke a better and fairer place by impartially enforcing the rules listed in the Duke Community Standard.

“I know that as a student, I’m not here to get people in trouble because it’s fun,” Bretz said. “I’m here to uphold the standards of the community.”

Another 2017 graduate—who served on about six to eight panels and asked to remain anonymous to speak freely about the UCB process—said that while she was at Duke, students did not join the board to punish others. They did so to either boost their resume, enforce the Duke Community Standard or because they wanted to bring a different perspective to deliberations. In her case, she joined the UCB because she had a critical perspective of the board and wanted to offer that voice, she explained.

Bretz added that OSC ensures the best possible students are selected for the UCB by allowing current panelists to have a large say in the interview process. She said the recruitment process included a mock panel in which interviewers simulated what a hearing would be like and evaluated applicants’ responses, for example.

Several former panelists cited having students on the panel as a strength of the student conduct process because students can bring a perspective that would be missed by faculty and staff.

Bretz and Vinesh Kapil, Trinity ‘14 and former UCB member, both said OSC made a substantial effort to assure diversity in the pool of students who might serve on any given UCB panel. As a former member of Duke Rowing, Bretz said she might be selected for an athletic case—provided that she did not know the accused student—because she understands the pressures athletes face.

She suggested something similar might happen if the case involved a fraternity or sorority member or a student in the Pratt School of Engineering.

The seriousness with which students approach their role on the UCB is a safeguard to ensure a fair and impartial process, said Larry Moneta, vice president for student affairs. He agreed that creating a student-oriented process is the best route forward—especially compared to disciplinary systems he has observed in the past, including at Duke.

“You got called into the dean's office like, 'What the hell did you do?’ You told your story, and that dean said, 'Get out, you're gone for a semester,’” Moneta said. “You've started in a model that was extremely informal, extremely disempowering to the student. The administrator in charge was judge and jury all at once.”

In the University’s system, there are several mechanisms through which a violation can be resolved. Students can opt for an informal resolution that does not create a disciplinary record for minor offenses, or they can go through a formal resolution. A formal resolution can either be an administrative hearing—in which an OSC dean decides if the student is responsible for the violation—or a UCB trial.

For the 2015-16 year, about 60 percent of all misconduct cases went through an informal resolution process, mostly faculty-student and residence coordinator-student resolutions.

“I think there are many steps before this disciplinary panel,” Bretz said. “Often times they don’t want it to get to a panel, which I think is really cool. They’re trying to do as much as possible to ensure it doesn’t get to that point because it’s kind of the last resort.”

Of the 396 students who went through a formal resolution process in 2015-16, the majority of cases were settled through an administrative resolution. Moneta emphasized that students always have the option to go through an independent UCB process if the student does not like the administrative resolution.

Several students who went through the process say OSC administrators presumed them responsible without hearing their side of the story.

Although Kapil said he does not think administrators go into hearings with that mentality, he also emphasized that there are students on the board for the purpose of representing student experiences, which likely differ from how administrators might perceive an issue.

Sue Wasiolek, associate vice president for student affairs and dean of students, defended administrators in OSC by noting their role as educators. Several panelists The Chronicle interviewed said they had positive experiences with the deans in various contexts.

“[OSC deans] didn't select this as a career in order to make life miserable for students who are accused of doing something wrong,” Wasiolek said. “They view their roles as educators and as really trying to give the student an opportunity to hold a mirror up to really reflect on the situation, and there are many many students as you know who get referred to the system and are found not responsible, and I believe that they aren't responsible or that there isn't sufficient information to find them responsible.”

Innocent until proven guilty?

Panelists recently willing to be interviewed by The Chronicle disagreed with the charge that panels fail to operate on an “innocent until proven guilty” basis.

For example, Brown said the panels he served on made a conscious effort to achieve unanimity in their decisions, although unanimity is not explicitly required to find responsibility—only a majority finding.

“Once we came to a decision, it was because we were all behind that decision, whether or not we were at that decision starting out,” Brown said.

But the panelist who opted to remain anonymous said that whether the “innocent until proven guilty” standard was upheld could depend on the composition of the panel. She cited an example in which she felt a panelist had been accusatory in questioning, but said this was the exception rather than the rule.

Several panelists also cited the quality of the deliberations as a factor leading to fair and impartial decision-making, with most noting that the deliberations took hours at the least and could sometimes go on for days.

Referring to the case of one student who said her hearing panel took only 11 minutes to deliberate, Kapil said this was likely an anomaly.

Other safeguards include that no panelist is allowed to know the student being investigated, Bretz said, and that panelists are not allowed to have information about the student’s past misconduct during the finding of responsibility stage. The Chronicle also spoke to students who said they were asked to waive their conflict of interest rights for logistical reasons. Robert Ekstrand, a Durham lawyer who has worked on hundreds of disciplinary cases, said that such waivers were common.

“[The conflict-of-interest procedure] was pretty extended, so I never served on any case where I had ever heard of any party,” Brown said.

Yet the most disturbing charge against OCS, reported by the Chronicle in its student conduct series, is that OSC investigators often provide incomplete reports to UCB and key witnesses are not allowed to testify. Legal experts, including Duke Law Professors Beskind and James Coleman, as well as Mr. Eckstrand and students, brought these deficiencies in the process to light.

The UCB process at the University begins with OSC staff gathering information and investigating the incident in question, before compiling an evidentiary packet presented to the panel. At the panel, accused students “may bring relevant material witnesses” to speak on their behalf. However, the panel has the authority to “determine the extent to which witnesses will be permitted, including relevancy of questioning and information presented.”

Several panelists interviewed said they felt the hearing packets presented to them were thorough and well-documented, often between 50 and 100 pages.

“There was never a point in time where I felt anything was being deliberately withheld from me,” Brown said.

None of the panelists could remember a situation in which a witness had been excluded from testifying either, and Kapil said that in his panels, at least one to two character references were either included via testimony or via written evidence.

Moneta and Wasiolek explained that issues or concerns about excluded evidence or witnesses—as well as new information—are within the purview of appellate panels.

Lingering concerns

However, some of the panelists acknowledged there is room for improvement in the current student conduct system.

Stephen Bryan—associate dean of students and director of the Office of Student Conduct—said panelists are not required to vote for a sanction when they vote that the student is not responsible. The anonymous panelist, however, said this was not adequately emphasized in her training.

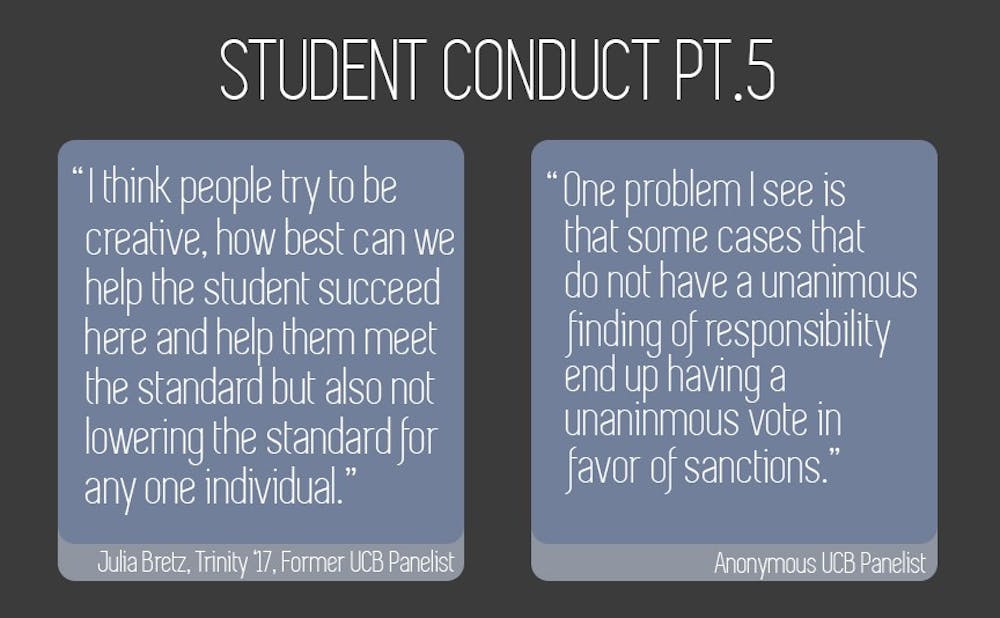

“One problem I see is that some cases that do not have a unanimous finding of responsibility end up having a unanimous vote in favor of sanctions,” she said. “I think that it would be helpful if UCB training emphasized that board members do not have to vote in favor of a sanction if they do not agree that the student should have been found responsible.”

According to University statistics, 47 students were suspended in 2015-16, 34 students in 2014-15, 32 students in 2013-14 and 33 students in 2012-13. The data does not indicate if these suspensions came out of UCB decisions or through administrative hearings.

The anonymous panelist said that she noted a mentality in favor of suspension during deliberations. She suggested that in deliberations there was a mentality that a suspension would promote academic and behavioral improvement, which she said is disconnected from reality because suspension is permanently listed on a student’s transcript.

She also said that students on the panel could sometimes forget their role as representatives of the student experience.

“The role of students on the board is to bring an awareness of the realities of student life and provide a peer perspective,” she said. “One issue that I have is that some students on the board get caught up in the process and end up being a little hypocritical, sanctioning students harshly for actions that are technically policy violations but are very common on campus.”

However, the other panelists The Chronicle interviewed did not agree that this mentality was prevalent.

Brown, Kapil and Bretz all said that panels deliberated intensely about sanctions to strike the right balance between helping a student grow and upholding the rules of the Duke Community Standard through appropriate sanctions.

Moneta added that this is built into the University’s policy. Normally, sanctions require a simple majority finding of the panel, but suspensions and expulsions require either unanimity on a three-person panel or a four-person majority on a five-person panel.

“The panel tries to take into consideration whether the student is going to thrive by being suspended but also as much as we want the student to thrive, we have to uphold the DCS, and there has to be a standard,” Bretz said. “From cases I’ve been on, people don’t want kids to get suspended. That’s almost a last resort, but if the case is severe enough, that’s what needs to be done.”

She added that she felt her attitude toward sanctions changed as she heard more cases. She came to the UCB as a strict upholder of the rules but the more cases she heard, the more she realized that strict punishments are not always practical and best for the student.

The panel has the option of assigning sanctions such as meeting with a counselor or reading a book and writing an essay to promote educational growth. However, Bretz noted these sanctions are often tacked onto suspensions or probations and not issued on their own.

For the 2015-16 year, 395 students were given a written assignment as a sanction, although the data does not indicate whether this was in conjunction with or separate from suspensions and disciplinary probations.

“I think people try to be creative,” Bretz said. “How best can we help the student succeed here and help them meet the standard but also not lowering the standard for any one individual?”

Although he did not think there was a UCB mentality towards suspension, Babboni said the stakes are often higher once a case gets to the UCB.

“If you’ve reached the UCB, it’s because the dean had a hard time reaching a decision, so by the time you reach the UCB you probably get a suspension or nothing because the more simple things are resolved by faculty-student resolution and dean,” he said.

Moneta added that another safeguard in the process is the amount of training panelists go through. He said panelists are presented with the University’s policy and are given training on how to ask good questions. They are also informed about proper and improper ways to approach a case and have the ability to observe a hearing before becoming a panelist.

That being said, the panelists The Chronicle interviewed had slightly different impressions of the training regime. Although Kapil said he was appreciative of the training, he did think more live training and shadowing of other panels would be helpful. Rob Spratley, Pratt ’14 and former UCB panelist, agreed.

“I wished it had been a little longer and a little more in-depth and that we could have done a little more practice, as in we have these rules so let’s see how it works in a case,” Kapil said.

He suggested that perhaps panelists should be specifically trained for certain types of cases. For example, certain students would focus on academic dishonesty, others on alcohol. Such a system is already in place for sexual misconduct, as only students who go through extra training can serve on those panels.

The anonymous panelist said there was not much follow-up to the training, which mostly consisted of a one-time five-hour session in the beginning. She suggested more follow-up not only about procedure but also about the role of student conduct itself.

She added that training materials tended to focus on cases in which someone had been found responsible and suspended, and less on cases in which a finding of not responsible was made.

Bretz, on the other hand, told The Chronicle that there were several training seminars during her first year on the board, and Babboni noted that deans had an open door policy to ask questions at any time for those in the student advisor role.

Bretz said she went through a follow-up implicit bias training session. She agreed that the training was thorough but noted the inherent time limitations all students face.

“These are students, and although being a part of the conduct board is really important to people, it’s not necessarily more important than school, so I think they’re doing the best they can to make us the best at what we’re doing and not to overwhelm us,” she said.

Still, it can be difficult to assure completely consistency across cases. Babboni said he observed this in his role as a disciplinary advisor across about 24 cases.

A student disciplinary advisor, he explained, are assigned to students when they first receive the letter from OSC outlining the allegations against them. There is also a faculty/staff advisor in case the accused student feels more comfortable discussing their case with this individual.

From there, Babboni said the role of student advisor largely depends on how the accused student wants to use him.

Sometimes he just reassures students about what they are facing and explains the next steps in the process, although he noted it is hard to say too much because he cannot tell new students about other students’ cases. Other times, he might be asked to help students write their initial response letter to the allegations.

“One of the biggest weaknesses is that it is difficult to be super consistent with these cases,” he said. “I can’t promise a student that because they did this and this and another person did the same that they’ll get the same result, because the process changes based on how students present themselves, if they’re aggressive or if they’re upset with themselves or upset with the process, and one of the roles of the advisors is discussing how to represent themselves. There’s a little bit of wiggle room that makes it difficult for students to have exact expectations about how a process will finish.”

Kapil suggested that one of the major shortcomings of the UCB, at least when he was there, is its communication. He said the body does not actively promote its work very well, in terms of connecting with the student body and explaining its role as representatives of students.

He added that some of the hostility OSC faces might stem from this lack of communication because students do not learn about how the process works until they are forced to deal with it. Improving communication could also ensure students realize the consequences of their actions, he said.

Modifying procedures

Moneta said that there is an institutionalized process in OSC to modify procedures, starting with the student conduct advisory group which includes Duke Student Government representatives.

According to the OSC’s website, there is also a representative from the Honor Council, the UCB, selective living groups, Greek organizations and the East Campus Council. However, the names of these representatives were never updated online for 2014-15 and 2015-16.

This group, Moneta said, issues recommendations, and then at the end of the year various staffers in OSC come together to further discuss the recommendations. Lawyers for the University are also present such as University Counsel Pamela Bernard, Moneta said, but they are not given a decisionmaking role.

“Technically, I get to make the decision. I'd like to say in 16 years, I don't know of a single occasion where I've said, 'You all want to do X. I'm going to do Y,’” Moneta said. “It's a consensus-driven process. There have been occasions where I said, "Y'all want to do X, but I don't think we have enough information.’”

Both Wasiolek and Moneta stressed the role of the appeals board in preventing miscarriages of justice in the student conduct process, with Moneta saying they have full authority to suggest a case should be reheard.

In the 2015-16 year, of the 16 cases appealed, only two saw the initial UCB outcome changed. Four of the 17 cases appealed in 2014-15 were changed, and two of the seven in 2013-14.

“I trust the process. It's not a perfect process,” Wasiolek said. “There will be mistakes made, there will be errors made. My hope and trust is that the appellate process will then kick in and it will work and if I didn't trust the process, I couldn't work with it. I would tell you the same thing about the folks in student conduct.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.