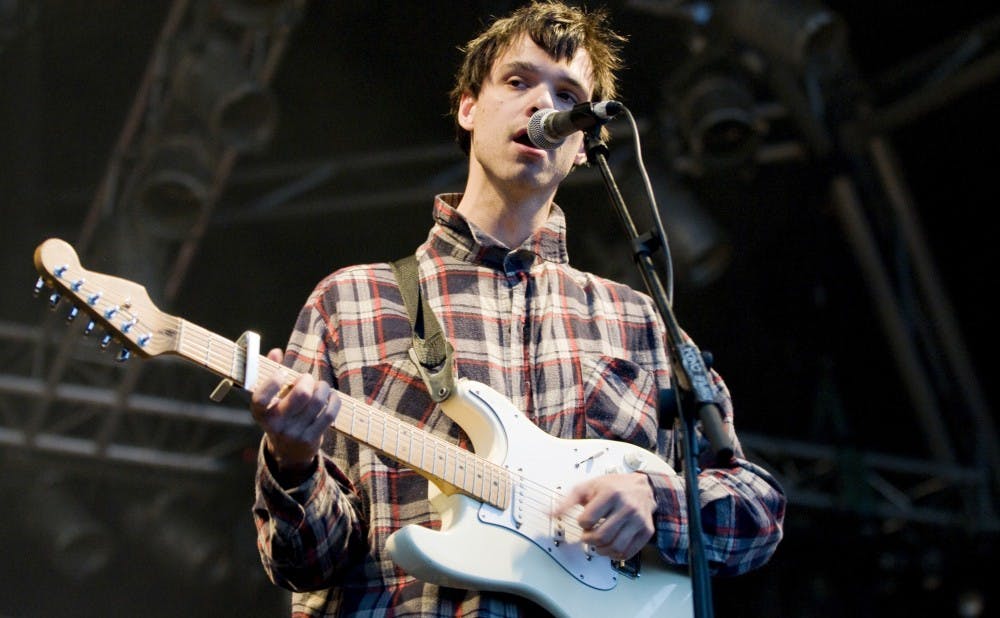

David Longstreth would like everyone to know that he is not going solo.

Still, it’s hard not to judge otherwise with the release of his band’s latest album, the self-titled “Dirty Projectors.” Even its eponymous title, an unusual choice for an act that’s over a decade old, feels like a reclamation of identity, a statement of purpose.

When Longstreth released the album’s first single, “Keep Your Name,” last fall, his isolation was apparent: the song begins with his voice alone save a spare piano arrangement, gradually intertwining with and racing against itself. The former members of the band were there, in some sense, but only as a warped, ghostly sample from one of Dirty Projectors’ own songs, 2012’s “Impregnable Question.”

The track was wacky and bold, if melodramatic. (“Dirty Projectors goes hip hop” is as weird as it sounds, yet it’s not an inaccurate description of what goes on here.) The subversion of the steadfast devotion of “Impregnable Question” into the bitter kiss-offs of “Keep Your Name” captured the direct aftermath of a relationship, when memories become tainted and distorted. As a one-off single, “Keep Your Name” was brilliant.

Building a whole album in this mold, though, is an entirely different matter. For the most part, that’s exactly what “Dirty Projectors” does.

The absence of Amber Coffman, Longstreth’s ex-girlfriend and ex-bandmate, hangs heavy over the album, and the concreteness with which Longstreth addresses her is sometimes unsettling, with specific names and places interspersed between platitudes about love and loss. Lyrically, it’s the equivalent of a voicemail you immediately regret leaving. “Dirty Projectors” is a candid examination of the post-breakup echo chamber that is one’s own brain—but is that really something that needs to be vocalized?

As a result, the record comes across a little too diaristic, a little too self-indulgent. It’s full of name-drops to Longstreth’s own touchstones—he calls out everyone from Gene Simmons to Bowie to Kanye to Tupac—but it seems none are as worth referencing as Dirty Projectors itself. Longstreth alternately boasts that “what I want from art is truth, what you want is fame” (“Keep Your Name”), narrates his relationship issues in the third person (“Work Together,” otherwise a highlight) and seems to swipe the credit from Coffman for one of his band’s best songs, “Stillness is the Move” (“Up in Hudson”). While the interpolation of “Impregnable Question” into “Keep Your Name” was a clever move, these instances scan as navel-gazing at their most innocuous and belittling and arrogant at their most brazen.

Musically, “Dirty Projectors” continues the streak of reinvention Longstreth has made between every album since 2009’s “Bitte Orca.” The band’s vice has always been over-indulgence, but here Longstreth channels that instinct into frenetic beats and glitchy electronics that bear as much resemblance to “Yeezus” or “22, A Million” as to anything in Dirty Projectors’ catalog. Like Tame Impala’s Kevin Parker, Longstreth has drifted more and more into pop star territory as he makes the project his own, trading the tropes of rock for those of R&B and hip hop to craft pop music that’s as accessible as it is off-putting.

In doing so, he’s consciously completed his evolution into that most hallowed territory in rock music: the auteur, the one-man band. But without the talents of Coffman and Angel Deridoorian (who also left the band in 2012) to complement him, Longstreth sounds more limited in scope even as his focus is more assured. “Dirty Projectors” sounds like the work of a man isolated in his vision and aware to a fault that, like Gene Simmons said, “a band is a brand.”

Another act releasing an album in the coming weeks, The Shins, underwent this transformation as an artistic vehicle for frontman James Mercer. After an “aesthetic decision” led Mercer to part ways (read: fire) his bandmates, The Shins became a bona fide one-man band beginning with 2012’s “Port of Morrow.” Out March 10, “Heartworms” continues in this vein, and if the singles released so far are any indication, the results are tepid.

Numerous artists have pulled this trick before: Lilys, Guided by Voices, Neutral Milk Hotel, Bright Eyes, Mountain Goats, Tame Impala. At its best, the one-man band magnifies the artistic vision of an individual under the guise of a full band. At its worst, it can seem like a deliberate, self-aggrandizing ploy for credibility—and, it should not be forgotten, it so often comes from a place of privilege (see: Two White Guys Declare Indie Rock Dead Since 2009).

As their careers have progressed, Mercer and Longstreth fall increasingly into the latter camp. With their recent output, each has retreated into an insular outlook, one that suggests they fear, just as much as their fans do, that their best work is behind them.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.