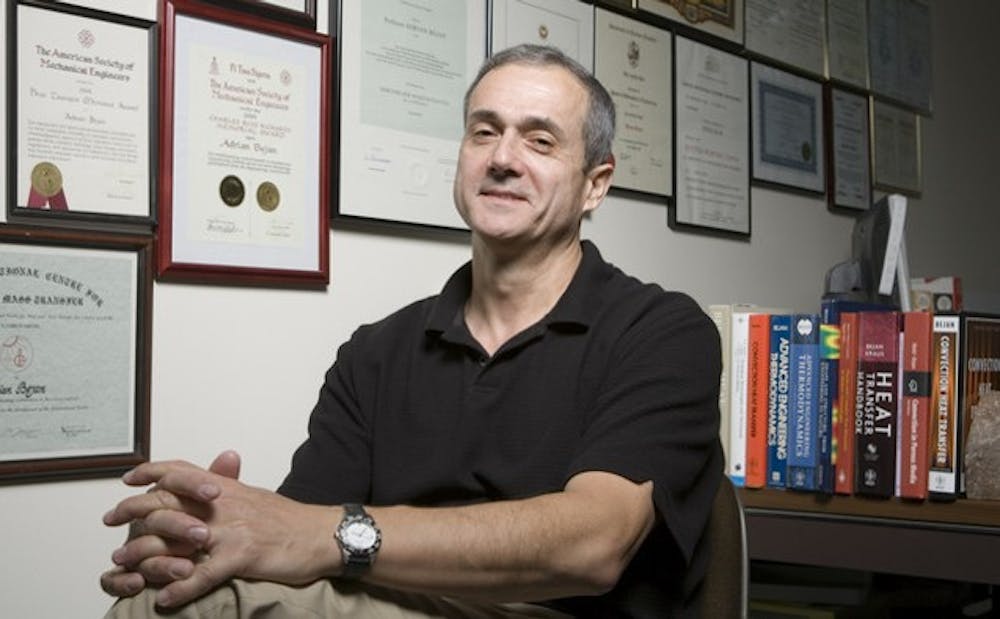

Adrian Bejan, J.A. Jones professor of mechanical engineering, was recently published in the Journal of Applied Physics for his explanation that wealth inequality is governed by constructal law, a theory in physics about the generation of design in nature. The Chronicle’s Rob Palmisano spoke with Bejan about his discovery and its future implications.

The Chronicle: What inspired you to investigate wealth inequality as the next potential application of constructal law?

Adrian Bejan: I was not inspired, but more of a flash in the night. Last year, during the election campaign, everyone was talking about inequality and, even before that, the recent news on that subject during the past [presidential] administration indicated that inequality was sharpening. In spite of efforts to mitigate it, things are going the wrong way. As far back as a hundred years ago, the West was always getting wealthier, but it was not as stratified as it is today. So there was no inspiration except my reaction that this is obviously an “obvious” phenomenon, and there are many people who don’t realize how obvious it is.

TC: Can you describe more of the theory behind your conclusion?

AB: This result is based upon the constructal law concept of "flow architecture"—that every system on the surface of planet Earth that is consistently interacting with its environment is a living system, and these systems resist this environmental exchange to varying degrees, creating a hierarchy of movement that is also synonymous with wealth distribution. The power that generates movement comes from fuel, and the fuel that is spent by any group or territory is proportional to what people measure as [Gross Domestic Product] of that territory. So it is a fact that movement is hierarchical, which translates into the conclusion that the economies of individual territories must be hierarchical as well, and that is nature.

Man has always worked with nature. There are things that we learn to do with rivers—to install hydroelectric power plants or to build dams, for instance—but if you try to do them everywhere, then the rivers revolt against this "unnatural" design, and remove it. It is the same as the struggle of mitigating inequality. One cannot create equality overnight. The history of human society has demonstrated that, very sadly. What can be done is to first realize that the flow architecture, in order to change, in order to evolve, must have freedom. Freedom is key to effecting changes. In the 20th century, we have everything from taxation to welfare, but most importantly, we have education enforced as a national policy to give everybody a chance, and so as I said, the citizens everywhere know much better what to do with the new knowledge than others who may be being told what to do with it.

TC: What was the most challenging part of this particular research?

AB: There was nothing challenging about it. It was actually a surprisingly happy piece of scientific life. This light bulb happened when a visitor from Brazil was here last July—the co-author of the paper. We chatted about it, and it was a very pleasant, easy ping-pong match of not only doing the math, which is actually elementary math, but also the graphs and then the narrative. Then, we published it in a physics journal, which is not always easy for those who come from engineering. So we are very rewarded by the fact that the physics peers have embraced this law of evolution in nature which is the constructal law, because physics is the big tent under which everything that is of interest or useful to humans resides. In my view, engineering is applied physics, and so is chemistry, government, urban design and now wealth inequality.

TC: Who would you say is your primary audience?

AB: I dream that my primary audience is the unbiased, naturally curious reader without an axe to grind, especially the "nobodys." My own entrance into science is the journey of an amateur, not someone who was trained to be doing this. My training was very classic at MIT—let’s test this, design this and then try and convince others to buy it. And then I discovered, through freedom [to ask whatever questions I wanted], that I like to focus on fundamentals, especially thermodynamics, which is the physics of power. And I like it more and more, and here I am today. I get to talk about the things that I’m not supposed to talk about—physics, economics and the social sciences, too.

TC: Who do you think serves to benefit the most from your discovery?

AB: Everybody, because society as a whole—the whole organism—must be thriving in order for any group to benefit. If the organism is dead or dying like the country in which I was raised—that’s the 50s and 60s in Stalin’s Romania—then everyone is poor and miserable and dreaming of leaving or running away. So the answer is any group. [Otto von] Bismarck once said, “Politics is the art of the possible.” He was right about that, but a funny way of saying it is that politics is the art of knowing what is impossible, so that you don’t waste your time with [the impossible], and you’re a lot less likely to make mistakes. So the way forward is that if everyone is better educated on the subject of what is possible and what is impossible and then how to go about implementing what is possible, then everybody benefits. Because with science, the new generation is brought up with greater power to design the future. Every generation has its unpredictable ingredients of people with new ideas, and that’s why the future is a very good picture to paint. And the better the science, the better the picture.

TC: What advice would you offer students who similarly have a question they’d like to get answered?

AB: Focus on your studies first, that’s what I always do. But there’s always something interesting if you keep your eyes open and if you are not afraid to question what you see or what you hear. One should not shy away from questioning authority. And this shows through in the way that I teach my classes.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.