Until now, starvation during life’s early stages was thought to exclusively lead to chronic health problems, but a recent study suggests that starvation could actually have benefits.

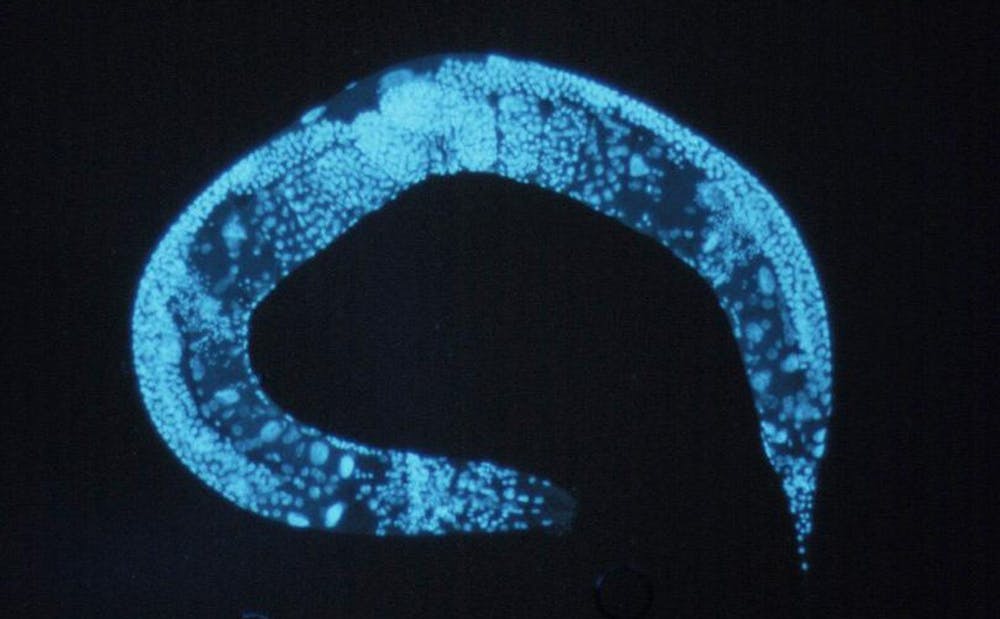

Researchers in the Baugh Lab at Duke found that mother nematode worms with low nutrient availability bred offspring better able to adapt to periods of famine. The advantage lasted throughout the worms' lifetimes, as they were able to make better recoveries even after the famine was over.

Ryan Baugh, the assistant professor of biology who led the team of researchers, said that before this study, “nobody had described the intergenerational or maternal effects” of dietary restrictions on lifespan.

In the study, researchers fed one group of pregnant worms normal food but gave another a watered-down version. Once the worms were born, the team measured the worms' growth and fertility during their first eight days of life, without giving them any food.

The growth of worms born to undernourished mothers was less stunted compared to those with well-nourished mothers. Although the effects of famine were not completely avoided, the impact on the starved worms was buffered.

However, worms in the study that did not face famine during their first eight days did well regardless of the whether or not their mothers had experienced starvation.

The researchers noted that restricted nutritional access during pregnancy activates some mechanism in worm mothers to produce larger eggs more fit to thrive in future famines. Baugh said that he was unsure what those mechanisms were but explained that they could be “epigenetic or genetic.”

Jonathan Hibshman, a graduate student in biology who conducted much of the research, noted that worms were used in the study because they serve as a “good model system and genetic system.”

Baugh explained that because the worm populations exist in states of “feast or famine,” they have well-honed responses to food-developed stress.

In addition, their short generation span made it easy for the researchers to study multiple generations, he said.

Baugh’s interest in this research area began with the thrifty phenotype hypothesis, or the idea that underfed pregnant women's babies have better metabolisms to ration nutrients.

He noted that the results were different from what he initially set out to measure.

“Originally, I was just interested in how [worms] could start and stop development when worms are starved and then fed again," he said. "Gradually, my interests grew into the long-term consequences of having this experience.”

Despite the findings, generalizing the results to humans is a "stretch" due to differences in life spans and generation times, Baugh said.

The researchers are hoping to dive deeper into the results they found.

“I’d like to follow up on the mechanisms that are causing the buffering effect,” Hibshman said. “[The findings] show that there are some genes that regulate this phenotype and also epigenetic mechanisms at play.”

He said that there is more research to be done to determine how the study's results could relate to other organisms.

"[I'm hoping for] follow-up studies in other mammalian system to see which mechanisms are conserved,” he said.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.