Fewer Duke students are choosing to attend law school after graduation, reflecting a national post-recession trend.

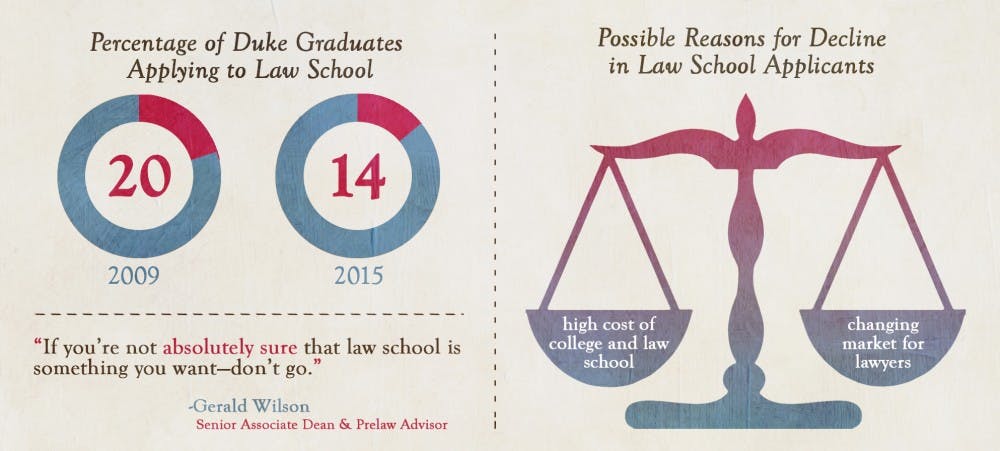

Gerald Wilson, a senior associate dean and the University’s prelaw advisor, estimated that the percentage of Duke graduates applying to law school has decreased from 20 percent to approximately 14 percent over the last four years. Thirty percent fewer students nationwide entered a private law school and 18 percent fewer students entered a public law school in 2009 than in 2015, according to the American Bar Association’s 2015 Report of the Task Force on Financing Legal Education.

Wilson attributed some of the decline to a changing market for lawyers, noting that technology is now able to perform tasks that lawyers used to do such as filing taxes. He also indicated that the high cost of undergraduate education and law school was also a factor.

The Wall Street Journal reported last year that the average 2015 class graduate will have a debt of a little more than $35,000. According to the ABA report, the average debt for private law school students increased from $102,000 in the 2005-06 academic year to $127,000 in the 2012-13 academic year.

“I try to make students aware of the realities of law school and the job market and also financing law school,” Wilson said. “I just want people to make realistic choices.”

Due to financial pressures, many students take one or two years off to work in the private sector or for non-governmental organizations, noted Joseph Grieco, a professor of political science who teaches a course on international law. Because of this, fewer students commit early to going to law school, he said.

When Grieco taught his international law course in 2009, he said that about 60 percent of his students were prelaw compared to the current 30 percent.

To advise students on financing law school, Wilson provides students with a guide book called Financing Your Legal Education: A Guide to Understanding the Cost of Law School and How to Pay for It from the Access Group in addition to a compilation of websites on loans. Wilson also invites Stephen Brown—associate dean of enrollment at Fordham University School of Law—for an annual workshop on financing law school.

The Duke Law School has also responded to applicants’ financial concerns, said William Hoye, associate dean of admissions and student affairs for the Duke Law School.

“We have been very aggressive in raising money for our scholarship endowments that have allowed us to greatly increase our reserves of scholarship funding,” he said.

Wilson said he tries to be frank about students’ chances at admission to specific law schools and pitches alternatives when necessary. Similarly, he attempts to discourage students from applying to law school unless they are certain about the choice, he said.

“If you’re not absolutely sure that law school is something you want—don’t go,” Wilson said. “And don’t go to any graduate school until you have a real reason for going.”

Duke does not designate specific courses as prelaw or have specific legal majors, a trait shared by many of its peer institutions. Of the 35 member institutions belonging to the Consortium of Financing Higher Education, 28 do not have majors, minors, certificate programs or concentrations specifically relating to law.

These schools—like Duke—echo the ABA’s guidelines, which “do not recommend any undergraduate majors or group of courses to prepare for a legal education.”

Eight universities in the consortium, however, do offer academic programs specific to the law— Mount Holyoke College, Northwestern University, Oberlin College, University of Chicago, University of Pennsylvania, University of Rochester, Washington University in St. Louis and Williams College.

These institutions, however, do not necessarily formally designate these academic programs as prelaw nor do these programs run the duration of a students’ four years.

“[These programs] certainly [don’t] harm one’s chances, I can’t say [they] would necessarily be seen as a strong plus factor,” Hoye said. “One doesn’t need to study law as an undergraduate in order to do well studying law in a professional program.“

In addition, Bowdoin College and University of Pennsylvania offer B.A./J.D. programs that allow students to apply to law school early. Cornell University offers a summer prelaw program in New York City, and Oberlin College offers a year-long program on the law.

While Hoye acknowledged the appeal of these programs to students who want to reduce the amount of time spent in undergraduate, he also noted that because law schools and employers value the experience and maturity of older applicants, Duke is currently not interested in offering a B.A./J.D. program.

“Encouraging students to come to law school at an earlier age is, at this point, not something we would probably be interested in doing, though we are certainly not ruling it out,” Hoye said.

Wilson explained that the lack of a specific prelaw academic curriculum at Duke is not a setback to students considering a legal career.

“Take what you want, major in whatever you want, do it well,” Wilson said. “Learn to think both analytically and synthetically. And learn to communicate, especially written communication.”

He added a recommendation that prelaw students take macroeconomics, microeconomics and accounting, but emphasized that these courses are not required for law school admissions and are simply very helpful from his point of view.

Because there is no set curriculum, Duke does not have a strong prelaw social community, former prelaw students said.

“Without classes, there’s really not much in the undergraduate atmosphere to base a whole community around,” said Katherine Coric, Trinity ‘16, who will be attending New York University School of Law this Fall.

Lauren Moxley, Trinity ‘12 and a 2015 graduate of Harvard Law School, also noted that the only prelaw community she experienced at Duke came about during the application process.

However, Moxley explained that the lack of community was not a disadvantage.

“A lot of it has to come from yourself,” Moxley said. “The LSAT for example—you need to do what you need to do to get motivated.”

Coric noted that doing specially law-related classes or activities is not necessary to enter law school.

“[My internships] were definitely the only law-related thing I added to my life,” Coric said.

Though Duke might not have a strong social prelaw community, Coric explained that Duke does have an undergraduate prelaw society called Bench and Bar.

Bench and Bar president Jacqui Geerdes, a senior, said the organization aims to help prelaw students get ready for law school.

“We help prelaw students at Duke find resources to help them prepare for law schools. Sometimes we’ll bring in companies that do free practice LSAT tests,” Geerdes said. “We help students figure out if law is something they’re interested in.”

Coric also noted that Duke does have courses relating to law, even if they are not formally designated prelaw.

Kip Frey—professor of the practice of public policy and law and director of the law and entrepreneurship program—teaches a course on intellectual property law and policy. He said that although many prelaw students take his course, it is still not formally prelaw.

“Having taken some law classes, I felt like I had a really good grasp of what a law class was going to look like,” said Lauren Goldsmith, Trinity ‘09 and a 2016 graduate of University of California, Berkeley’s J.D/Ph.D program. “I took a constitutional law class [at Duke] and as a law student it was essentially the same format and the same style of teaching for the most part.”

While doing well academically is important, Wilson also noted that he encourages students to take interesting and stimulating courses.

“You are cheating yourself if you don’t take good, challenging courses that are of interest to you,” Wilson said. “And within reason, take professors, don’t take courses. That’s where you’re going to really learn.”

For example, Goldsmith—soon-to-be associate in the litigation practice at international law firm Sullivan & Cromwell LLP—said she wonders how her career might have been different had she completed her math and science requirements earlier in her academic career and discovered her interest in those subjects earlier. She noted that science majors can take the patent bar and become patent lawyers.

Wilson estimated that about 10 percent of prelaw students at Duke studied engineering.

“There are a lot of opportunities for people from all walks of life, academically speaking,” Goldsmith said. “I’ve been in classes with people who have Ph.D’s in chemistry, engineering, biology and literature. As long as you went to a school that’s rigorous academically, you can do well in law school.”

“We are especially interested in students who come from STEM majors because we know that there will be so many more legal jobs developing in the future that will require really technical skills,” said Hoye. In addition to STEM majors, he also mentioned economics and finance as fields that would allow applicants to both be competitive for employment and adaptive to emerging industries.

Goldsmith also defended Duke’s lack of a prelaw curriculum, noting that it prevents homogeneity.

“You don’t want everyone coming out of Duke looking exactly the same,” she said. “I think it’s good that Duke encourages them to pursue whatever they love and are excited by. You can get to law school no matter what you study.”

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.