Duke faculty are divided on the issue of unionization.

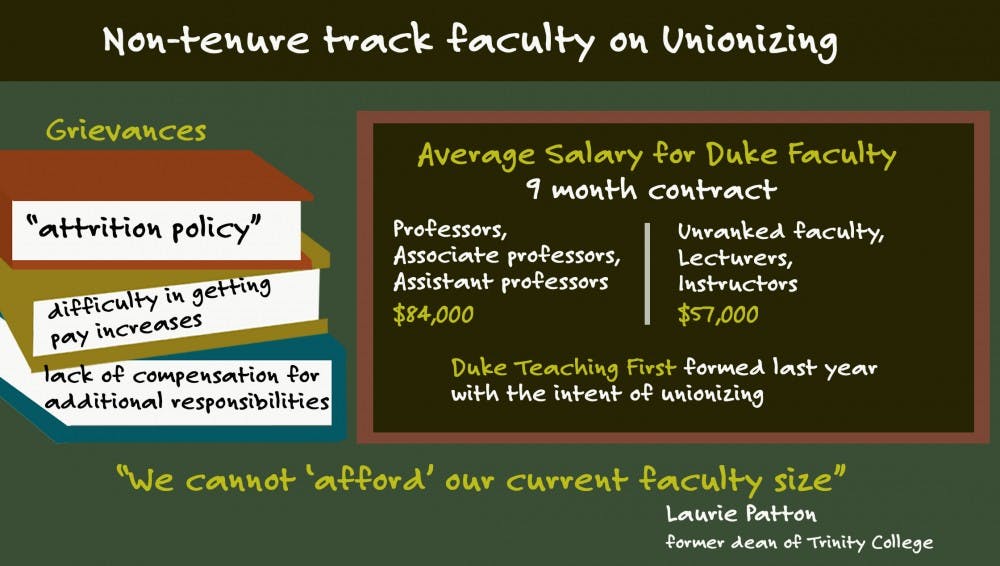

Members of Duke Teaching First, an organization of non-tenure track or contingent faculty, filed a petition with the National Labor Relations Board asking to be represented by the Service Employees International Union last Thursday. Faculty and student activists pushing for unionization argue that contingent faculty do not have adequate job security and are doing some work without pay. Some faculty also allege that the University is pursuing a policy of attrition to lower faculty salaries and remove positions, citing emails from administrators stating that Duke cannot afford to pay faculty more. Other faculty members argue, however, that unionization would harm faculty and the University.

David Banks, professor of the practice of statistics, said he is discontent with his ability to get pay raises. Duke administrators have told him that individual negotiations with the department chair are the best way to earn a pay raise, but he said that his requests every two years for a small pay raise have been consistently denied.

“I’ve tried to work the system the way it was suggested,” Banks said. “It didn’t work, so now I’m happy to try an alternative.”

If the NLRB finds sufficient interest among non-tenure track faculty, then a union election will take place among such faculty in the Trinity College of Arts and Sciences, the Graduate School and the Center for Documentary Studies, according to the Representation Petition, which was obtained by The Chronicle. A majority of the faculty who vote in the election is necessary for the union to be created and begin negotiations with the University.

Grievances

The unionization push at Duke has grown as universities nationally continue to rely on contingent faculty while only providing short-term contracts, per-course payment and sometimes failing to provide benefits that tenure-track faculty have, said junior Zoe Willingham, president of Duke United Students Against Sweatshops, which has been supporting DTF.

“The quality of life for faculty has gone down,” she said. “A lot of professors have a hard time making ends meet, health care is a big issue, and that’s why faculty members are coming together to advocate for better working conditions on campus.”

DTF formed last year with the intent of unionizing in order to achieve greater job security and higher wages. The average salary for Duke professors, associate professors and assistant professors on nine-month contracts is more than $84,000, and the average salary for unranked faculty, lecturers and instructors at the University is less than $57,000, according to data released by the University to the Department of Education. At Duke, regular rank tenure track faculty are typically assistant professors, associate professors, professors and named chair professors.

Banks attributed non-tenure track faculty’s inability to get raises to the administration’s current “attrition policy,” which he described as a plan to manage finances by freezing new hires and encouraging attrition among faculty. In an email to faculty and staff last April that has been obtained by The Chronicle, Laurie Patton—former dean of Trinity—wrote that “we cannot ‘afford’ our current faculty size.”

“As we continue to move towards budget sustainability, our faculty hiring will continue to be both constrained and very strategic,” she wrote. “Moving forward, every hire and every retirement counts.”

Similarly, in an email from March 19, 2010 that has been obtained by The Chronicle, President Richard Brodhead wrote that “Duke simply cannot make permanent salary increases at this time without aggravating our future budget problems and jeopardizing jobs.”

Matteo Gilebbi, lecturing fellow in the Department of Romance Studies, agreed with Banks that non-tenure track faculty need more representation in order to voice both personal concerns and concerns about the University’s future to administrators.

Willingham said that non-tenure track faculty are sometimes expected to fulfill responsibilities that they are not compensated for handling. Gilebbi noted that his contract only requires him to teach and mentor students, but that he additionally does research and presentations at conferences for which he is not compensated.

“It’s something we want to do as faculty at Duke because it’s a great institution,” Gilebbi said. “It’s not in the contract, but it’s something I personally do.”

Gilebbi added that longer contracts and solidified career paths would encourage and motivate non-tenure track faculty to focus on further research projects. DTF’s goal is not to eliminate the pay gap between contingent and tenure-track faculty, Willingham noted, but rather to make sure that the work contingent faculty currently do that goes unpaid is actually recognized.

The hiring of non-tenure track faculty at Duke has increased by 67 percent in the last decade, compared to 11 percent for tenure-track faculty, according to the Task Force on Diversity’s report to the Academic Council last May.

Divided faculty

Not all contingent faculty, however, are in favor of unionization. A number of professors in the economics department have raised significant concerns with the proposal, for example.

Bruce Caldwell, research professor of economics and director of the Center for the History of Political Economy, said that raising the salaries of contingent faculty, while good for some, could possibly hurt others because the money for those increases could come out of other contingent faculty’s paychecks or lead to higher tuition costs.

Willingham noted that a lowering of some faculty’s wages would not happen because the negotiation would involve “wage floors” instead of raising some contingent salaries at the expense of others. A union contract reached at Tufts University in 2014, for example, required that by September 2016 all adjunct faculty make at least $7,300 per course.

Senior Lecturing Fellow Daniel Bowling at the Duke Law School, however, noted that pay trade-offs could still happen depending on how negotiations proceed.

“It is entirely possible any final contract reached might include a flattening of the differences so as to keep the overall cost of the contract acceptable to Duke negotiators,” he wrote in an email.

The University might also choose to hire even fewer contingent faculty moving forward as relative costs for pay and negotiating with the union increase, benefiting the current group of non-tenure track faculty but lowering the overall number of contingent faculty in the future, Caldwell said.

Bowling noted that because North Carolina is a “right-to-work” state, no faculty member will be forced to join the union or pay union dues, but that they would nonetheless lose the ability to bargain individually with administrators. The DTF website, however, said that individual negotiations would still be possible under the union.

“When we form our union, your relationship with your direct supervisor, provost or dean, is up to you and them,” the website reads. “Our contract will set a floor, not a ceiling.”

Professor of Economics Peter Arcidiacono, who is in a tenure-track position, said that humanities disciplines might be more likely to support unionization than faculty in fields such as economics, science, technology, engineering and mathematics who might be on the higher end of the contingent faculty pay scale. He also noted that these disciplines often have an easier time getting outside job offers.

Unionization also has the potential to diminish merit pay through mandatory pay scales, said Professor of Economics E. Roy Weintraub, who is also in a tenure-track position. He noted that this was his experience when teaching at Rutgers University, where faculty were represented by a union.

Charles Becker, research professor in the economics department, expressed concerns that unionization would damage faculty culture by creating stronger distinctions between management and labor, leading to less bottom-up initiative from faculty.

“Duke is unusually decentralized and entrepreneurial, surprisingly for a large nonprofit institution,” he said. “Management at Duke University is heavily driven by faculty, but unionization draws that line.”

He added that at universities with a more bureaucratic culture than what Duke has, he would likely be in favor of unionizing faculty, but not at Duke.

Administrative response

In the 1970s, the University stopped faculty unionization efforts within the Duke Hospital, noted Robert Korstad, professor of public policy and history. He explained that Duke hired labor management consultants to “defeat the union,” which included playing skilled workers against less-skilled workers. The unionization drives were ultimately unsuccessful.

Korstad added that Duke’s initial response so far has been similar to that of the past, including statements to faculty and the larger community indicating their opposition to the union.

"Although Willingham said Duke has not currently taken “union-busting” action such as meeting with faculty one-on-one or holding captive audience meetings, she said that the Duke One-to-One website, created by the University in response to DTF, paints the process in a negative light by framing the union as a “third party.”"

The purpose of the website was to provide accurate information to employees regarding the costs and impacts of unionization, wrote Michael Schoenfeld, vice president for public affairs and government relations, in an email.

“Non-tenure track faculty will ultimately decide whether to seek representation by the Service Employees International Union or not,” Schoenfeld wrote. “Duke supports their legal right to explore options and vote.”

Willingham also noted the University’s hiring of labor and employment law firm Ogletree Deakins, which is confirmed by the NLRB case file, and criticized the University’s refusal to commit to neutrality in the matter.

Bowling wrote that University would likely “work hard in good faith to reach some sort of agreement” should the union be formed.

Willingham added that the administration’s decision ultimately comes down to how it wants to treat students.

“Student supporters would be very upset at the administration if they perceived that Duke was willing to cut back on the quality of education just because professors have been asked to pay what they’re worth,” Willingham said.

Get The Chronicle straight to your inbox

Signup for our weekly newsletter. Cancel at any time.